The Dying Iris

Katie Bowers

“Don’t you want your doughnut, Marianne?”

She glances up at her husband seated across from her. The doughnut has been sitting on her lap for the past half hour. It’s a jelly doughnut coated with powdered sugar—Joey had said, “It’s raspberry-filled, your favorite.” His smile had been so genuine that it was hard for her to correct him, so she just thanked him and let the doughnut rest in her lap. Marianne prefers raspberry jam to all other jams and jellies, but she doesn’t really like jelly doughnuts. She enjoys thick doughnuts–heavy ones, almost cake-like; old-fashioned sour cream doughnuts are her particular favorite. He can never seem to remember this, to recall that raspberry jam is her favorite, but jelly doughnuts are not. She knows that he sees the word raspberry and thinks of her. For this, she should be grateful, but sometimes it is hard to be grateful for someone who is simply making the connections between word and object and vague memory.

Moving just her eyes, Marianne looks away from the window of the train and at her husband. She notices the new gray in the dark stubble on his cheeks and chin, the wrinkle of his Oxford. He looks comfortable—in their aging, in his unkempt shirt—and this nags at something inside her.

“I’ll eat it in a bit…” she says, studying him for a moment more.

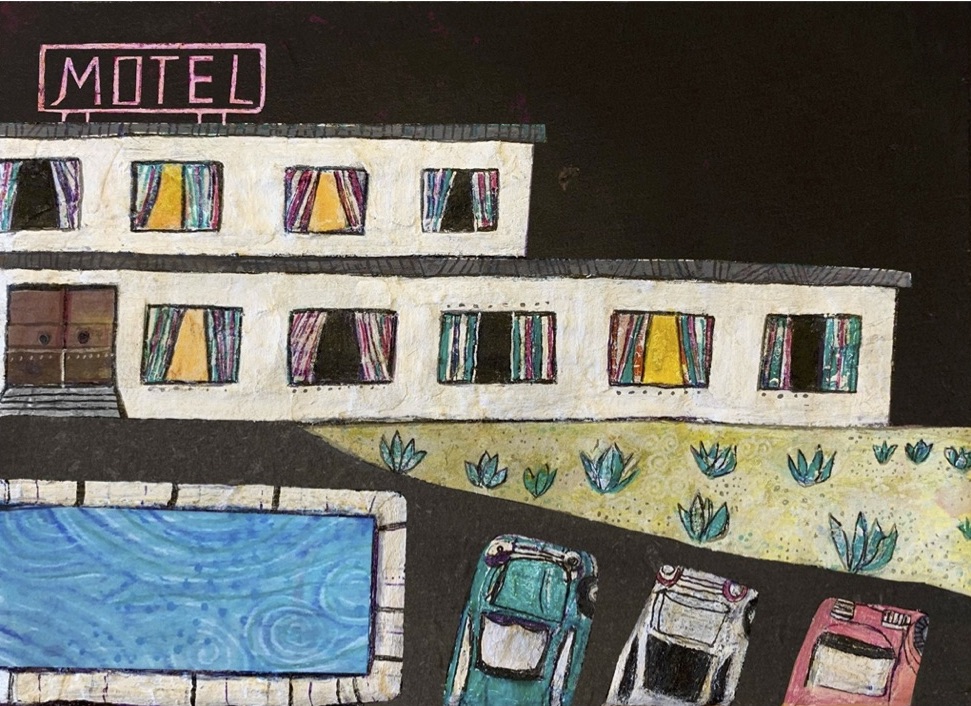

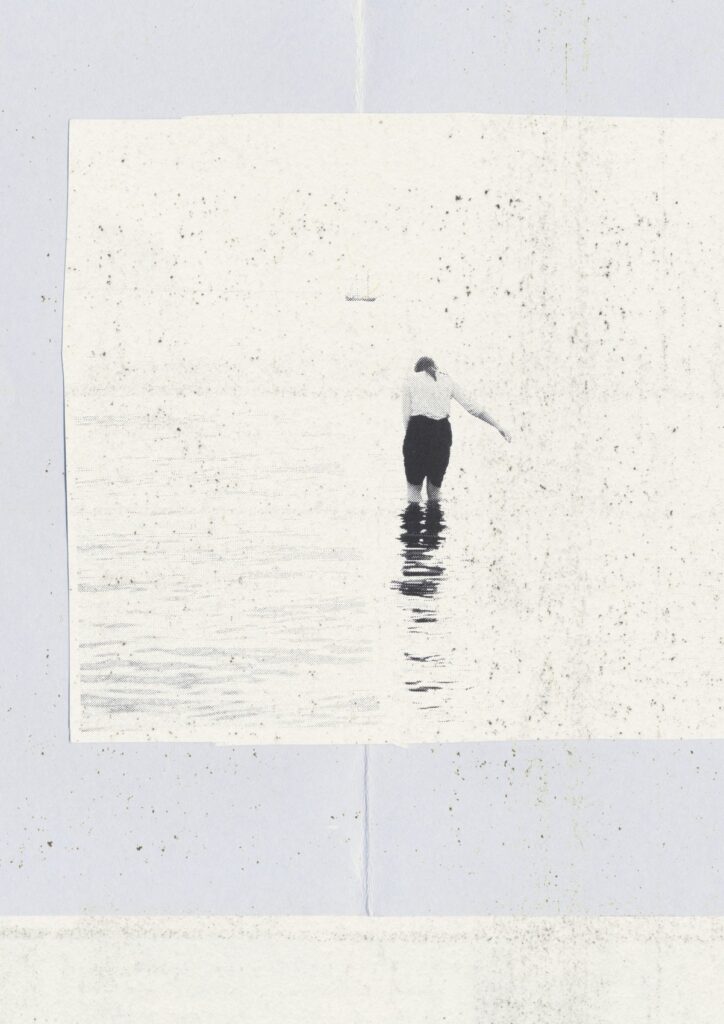

This train ride will take them home to Charlotte, the last two days of their month-long train-hopping journey spent in Atlanta—a city neither of them particularly cared for. They went to a baseball game where Joey found that everything was too expensive, and, ultimately, too boring. It was, forebodingly, not the most enjoyable way to end the carefully planned trip.

Sitting with a doughnut in her lap is not how she wants to begin the almost six-hour train ride back to Charlotte, which will follow, with traffic, an almost hour drive to their home. Back to exactly where they were before the journey began; except now, Marianne is pregnant.

The morning they left New Orleans, heading towards Birmingham, Marianne rushed to a Walgreens to buy a pregnancy test—not one with the lines or lack thereof, one where the words pregnant or not pregnant were shown behind a small plastic screen.

In the six years they’d been married, she spent years three and four buying pregnancy tests in bulk, peeing on stick after stick, and, when not seeing the results she’d hoped for, tearing the plastic apart, holding the tiny paper strip up against the light, hoping that the second line was too faint to see, that the light would reveal it.

They entered year five tired and angry at one another when, as far as doctors could tell, neither of them was to blame. Marianne just wasn’t getting pregnant. Until now.

Looking at her husband, he gives her a small smile, and she notes the sapphire blue of his eyes and how she used to want nothing more than to hold a baby with eyes just like his.

She no longer wants to be looking at him, but instead of looking back out the window, the blur of green making her nauseous, she shuts her eyes, her fingers resting around the napkin on her lap where the doughnut sits. Some of the powdered sugar has spread to the edges, dusting onto her skirt, and she can feel the chalky dryness of it against her left index finger, against her thumb.

Marianne likes a doughnut with a hole in its center. When Marianne was little, her grandfather told her to wear doughnuts like a ring. She’d taken to this, as it was a silly, simple joy.

On one of their first dates, she put a doughnut on her finger as she and Joey drank burnt coffee. When he leaned across the booth and took a bite out of her doughnut, she felt that she instantly loved him. Yet, he never seemed to consider this and only got her jelly doughnuts, which don’t afford the eater such a simple joy.

She thinks of how simple it would be to say, “Did you know, Joey, that I’m pregnant? Did you know that now that we’ve given up, now that you’ve had an affair, now that my mother has died, now that we’ve paid off our house that is too small for a baby, now that we’ve turned our only other bedroom into a room just for you, now that the world has filled us up with everything else–did you know that I’m finally pregnant?”

Marianne had almost had an affair—more of a reaction than a desire, and ever since she’d found out she was pregnant, she wished that she had done more than let that man hold her hand at her art gallery’s fundraiser while looking at a painting of dying purple irises, his hand new and foreign and distinctively not Joey’s. If she’d slept with him then, perhaps, she would not have gone on this trip, perhaps he would have been the father of this baby. But the field of irises made her realize that she was not willing to hurt her husband in the way he’d hurt her.

She hadn’t expected to become pregnant; she expected to bury herself in her job and find some semblance of contentment with Joey. But having a baby would require a closeness they haven’t had in years, a closeness he, she realizes, had perhaps wanted to restore with this trip.

She supposes she could have an abortion; she supposes she could leave Joey, never telling him about the baby; she supposes she could forgive her husband, herself, her stubborn womb.

She supposes, most of all, she could just eat the doughnut in her lap; eat it and enjoy it, jelly and powdered sugar coating her face and hand.

Katie Ellen Bowers is a writer living in the rural Southeast with her husband and daughter. Her debut collection of poetry. This Earthly Body through Main Street Rag is out now. Other works of her poetry and fiction can be found in literary journals and magazines such as Kakalak, Qu Literary Magazine, and Good Printed Things. She has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize for poetry twice.