The Upper City

by Dorit Silverman

translated by Maya Thomas

They drove within the speed limit through the green terrain of southern Italy, north of Naples, on their way to the Blue Grotto – the cave of joy. All of the tourists arriving at the region would take the main road, but they decided on an old highway with numerous side roads branching off of it. The summer there was the exact same as Israel’s, hot and humid. Noga delighted over watching the view as it split onto two scenes, revealing swift snapshots of nature. The road’s edges were gravel, coarsely-ground white pebbles, bordered by vegetation which had turned green in the winter and hadn’t been dusted since. To the right were low industrial complexes. To the left were mountains, not too tall, forested with small villages among them. Noga was holding onto an old brown silk jacket, caressing its soft lining. Her eyes were transfixed by the glimmers of her ring, directed towards the sunlight. The jacket and the ring were some of Noga’s most treasured items, having been acquired at the flea market.

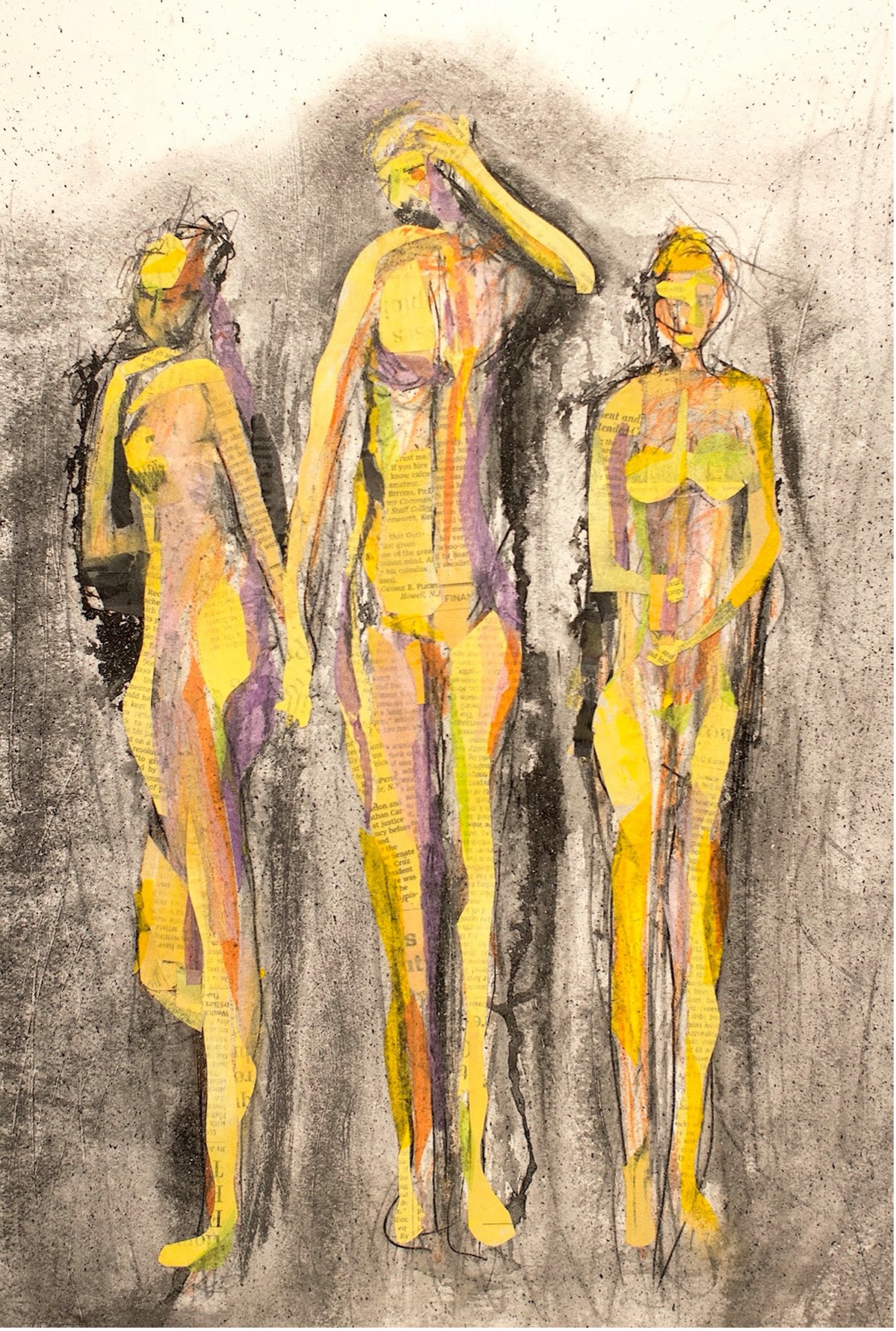

Noga: dark blue socks embellished with little flowers, cushioning her sneakers and revealing childlike ankles. Brown jeans and a white tank top with no bra. She could afford to do that, she was turning thirty in six months’ time and she still got compliments for the level of perkiness, despite two pregnancies and a lot of breastfeeding. The jacket was a just-in-case restaurant or museum situation. All of a sudden, within her daydream-like stare through the steady-changing scenery, she noticed some sort of movement from the corner of her eye. She lifted her head and spotted a narrow road on the right which was connecting to the highway. The connection was masked by a row of trees resembling cypress or fir, a little shorter than the typical Israeli cypress tree and less symmetrical than the fir trees she’d seen in Christmas movies. Behind the row of trees was a small movement that quickly turned into a light-brown car speeding in their direction.

What does he think he’s doing? Noga mumbled more in contemplation than warning, though there was no time for that anyway. The car grew closer at great speed, and within seconds it was too so for Ronnie not to notice it, but by that time it was too late. The car, which may have actually been grayish-green, drove at 60 miles per hour and crashed into them with the force of galloping stallions, with a thud that rattled Noga’s head, her skull turning into a jewelry box with trinkets flying all around inside it. She lifted her right hand to shield her face as the car took on a demonic kind of autonomy and surged towards them. Noga was propelled through the air, feeling the engine’s heat alongside the chill of the metal inside her body. Their Ford pivoted on its side, plummeting down as its roof banged onto the ground, wheels swiveling through the air like a cockroach stuck on its back and trying to resuscitate itself. The car rotated with great force around an invisible axis, like a bottle being spun during Truth or Dare in the playground after practice. The bottle halted in front of Noga. Come on, Noga, choose. Truth or dare. Truth, truth.

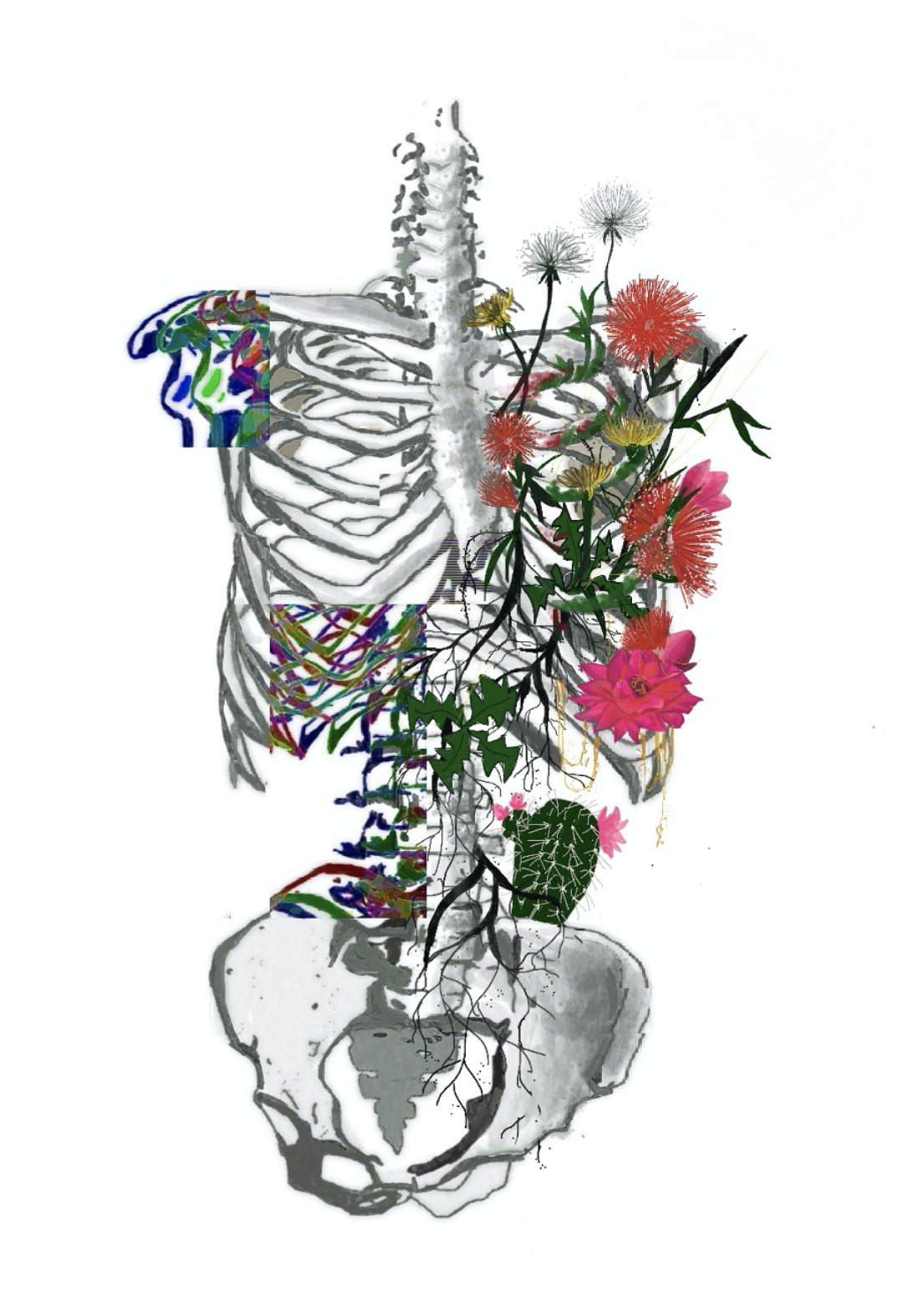

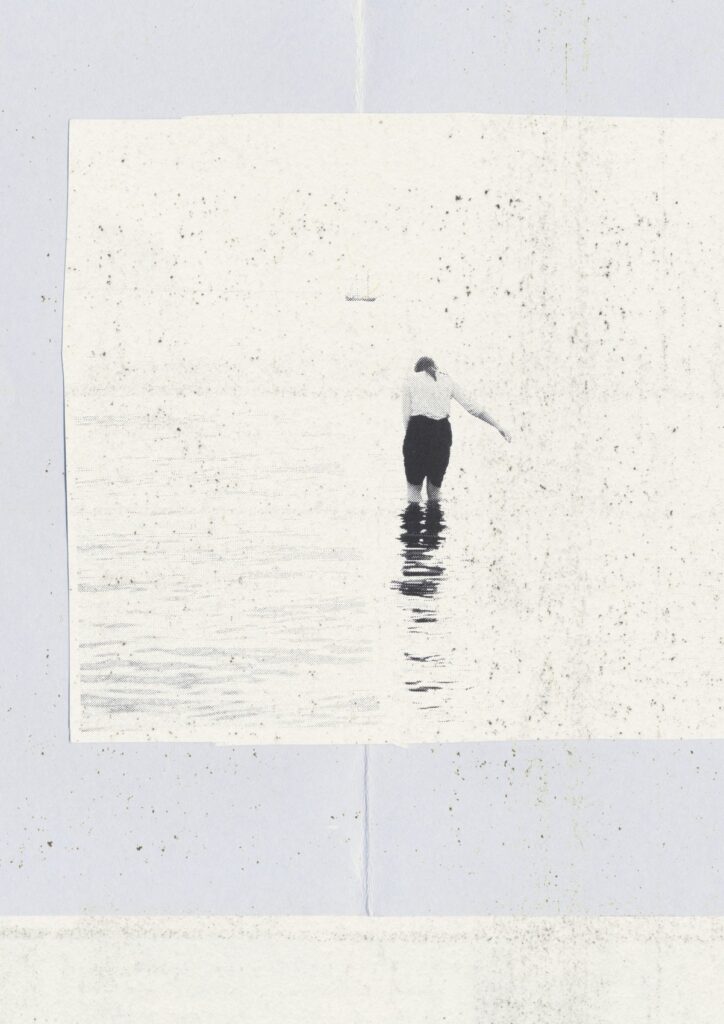

At that moment, hundreds–if not thousands–of bells started ringing through all of the southern churches, the trill of airplanes, the klaxon of rockets, a shower of gunshots, shattering glass, a colossal ruckus filling her head to the brim. The car door tore away and Noga was flung out, but the change started occurring in mid-air. Her body slowed down and retired from the race. She landed – without falling and only after a very long and incredibly pleasant time – on another planet, wholly white, beyond the atmosphere, no oxygen. Warm and pleasant. Her white tank top blew up like a canopy, providing a soft, gentle landing. It turned out that there was no need for legs in this new place. They gradually disconnected from the rest of her body, perhaps to enable better floatation through the air. She could hear voices but she didn’t see anyone. Her body was lying flat, but her senses had already been liberated of it. Blinded by the light, she couldn’t quite see all the details, but eventually she landed straight into water. Her entire body was submerged in water. It was a golden submersion in the late-afternoon light, twenty miles north of Naples and twenty-million light years away. A bearded man approached her–– You need to go through the water to get in. She accepted that. But what about the legs – she wanted to ask, sensing immense pressure on her legs. She tried to follow him but he grew bigger as she diminished. Her breathing was getting heavy. She could hear her own wheezing, but couldn’t decipher the signs. There were people around her speaking a language she didn’t know.

A familiar voice was heard from afar: Noga, can you hear me, give me a sign if you can hear me. Nothing. Someone shifted a barrier aside and oxygen penetrated her lungs all at once. She stopped her wheezing and breathed deeply, like a parched individual finally arriving at a freshwater pool, and now she could clearly hear someone calling her name and asking her for a sign of life.

Dozens of people had gathered around. Her tank top had rolled up and she was lying there with her torso exposed to the sunlight. A few modesty freaks came by wanting to cover her, but Ronnie shooed them away. Shouldn’t touch someone who’s injured, no way of knowing if there’s a broken vertebra, don’t touch her. Someone ran to the car, pulled out the jacket and tossed it onto her unharmed breasts, perked and pearly-white, as though sticking their tongue out at the passers-by. A thorny branch which had gotten stuck in her throat, throttling her head back, had blocked her breathing. Ronnie got it out. She started breathing at once. People called for an ambulance. There was shouting. Someone gathered all of their bags and luggage, which had flown out of the car, a woman came up to Ronnie and handed him his wallet, which had been flung to the side of the road. Ronnie thanked her. He wanted to get some cash ready for the ambulance and opened the wallet to have a look: the credit cards and the insurance attached to the flight tickets were all there. The three-hundred euros in cash were gone. He couldn’t do anything about it, he had to watch Noga. He shouted at her, trying to wake her up.

She opened her eyes and closed them again. It’s me, Ronnie, do you recognize me?

She blinked twice. Now he wasn’t shouting as much, and his voice sounded weaker, maybe he stopped speaking to her, maybe he was speaking to other people. She felt good. Didn’t have a care in the world, felt no pain. She had air to breathe, she lay there quietly. Soft, cool silk spilling over her body. It felt pleasant, she was covered, she wasn’t cold nor hot, she didn’t sweat or feel itchy, she laid there in the sun, on the side of the road, over the coarsely-ground pebbles which seemed more like little cotton pompoms. And then she was suddenly taken away from there. What a shame. She was rattled around but didn’t feel her body’s burden. She was put into a shaded, cool space, but it was none of her business. Someone else had taken all of her worries upon themselves. She didn’t know anything and didn’t remember anything. She had no children, no parents, no husband or sisters. It was just her and the scrawny guy who gave her a little smile and looked at her with his black eyes, blazing fox eyes, and walked slowly in order to lead her, so that she wouldn’t get lost. She didn’t have the energy to get up. But soon, she promised herself. Ronnie called her name again. She pointed her finger up. He asked things, she didn’t understand, but she knew through her natural-born obedience that she was required to give some sort of sign. She wanted to follow that guy, there was something so nice about him, and Ronnie was standing at the dead end. The guy was inviting and Ronnie was screaming, sick with worry. Why won’t they leave her be in the sun which was turning the water golden, breaking into fragments within it, dipping in it to cool itself down? She was floating through the sky, swimming in light. A late afternoon sun is like ripened fruit, a very orange hue of yellow, one degree away from the scent of slight rot, followed by sunset.

The swaying grew stronger. The ambulance jolted from lane to lane and drove over a partition in the middle of the road, bypassing the cars in the traffic jam, its siren drowning out all other sounds. Ronnie didn’t want anything from her either, and everything became quiet. Then, all at once, her mind was overtaken by the sirens of other ambulances parking at the entrance to Napoli’s Cardarelli Hospital, pouring out patients and injured people onto stretchers. People were yelling, someone was giving out orders. She was mobilized again, a long shaky commute on small wheels. It took a while for them to get inside. There were voices and rattling and a dark blanket separating her from them all. Now it was getting cold and dark. She lost consciousness and sunk into the darkness, glimmering golden threads interwoven within it. They continued rolling her ahead and then the rattling stopped, they slid her onto the floor. The journey was long, she was traveling within a deep, dark tunnel, perhaps a rabbit hole. A journey of four-thousand miles, until she finally came out on the other side of Earth, where people walked upside down, their heads on the bottom. Excuse me, Ma’am, is this Australia or New Zealand? The wheels halted. They pricked her, spoke to her in a beautiful language with swirling words, like colorful reels of thin ribbon, the kind you throw along with rice from the synagogue balcony. And then that man showed up again, the one with the long hair, beard, narrow lips as though drawn on by a delicate brush, calming eyes, thin eyebrows and a long nose, near the lips but not overly protruding. His mouth was shut, nothing but his eyes inviting her with so much warmth and softness, and there was no more light to protect her, it was so incredibly dark, so did she really have a choice in the matter?

She had to follow him.

He led her all the way to the stage, then humbly walked back to sit with the rest of the audience. She was surprised to see that the orchestra was ready for the performance. Noga was excited. She was immediately taken backstage, wheresomeone helped her prepare, then shoved her onto the front of the stage, dressed in a glimmering red sequin dress, wholly composed of tiny flickering dots of joy, black-cherry lipstick to match. This was her first ever stage performance. She began delighting over what was to come. Someone introduced her. Reserved applause, well, no one knows me here, she consoled herself, but after the show I’ll get a standing ovation, she was sure of that. She held the microphone with both hands, the way she imagined famous singers must do, gave a little smile to mask the dazed sensation of standing in front of such a huge crowd. Noga heard the words ‘cabaret singer’ and knew that it was time. The sounds of the opening were heard. Noga turned back to get a final green light from the conductor, but what is that? What does he think he’s doing? She was mainly speaking to herself, in a quiet tone of reverie rather than warning. The conductor approached her and directed his baton to a spot between her ribs. Her eyes searched for the man who’d brought her there, the one she trusted so implicitly, as the baton sliced through the air with hummed momentum and pierced into her. The sparkling-red sequin dress tore and all the sequin scattered around her. She’d wanted to sing so badly that her mouth became filled with a salty-sour taste. For years she’d practiced her singing, and she’d finally almost gotten her chance. From the outside, all you could see was a delicate stream of blood at the corner of the mouth, but she was losing oxygen, her abdomen filling with blood. She used all the energy she had left to row through a green mush of mold and a blanket of spiderwebs and peeling drywall and light-pink bricks and photos of saints and sounds of weeping and the scent of secretion and soiled sheets and rays of gold, of copper and light coming out of the rianimazione ward, the resuscitation ward. The surgery had come to an end.

The doctor came out to the hallway. He told Ronnie to go rest, there’s nothing for you here, but Ronnie wouldn’t go.

“She’s lost without me, she doesn’t know the language and she won’t know what’s going on if she doesn’t see me.”

Ronnie watched Noga through a window that wasn’t large but framed his body from the chest up, so that he could stand comfortably. He saw old beds, sheets wrung of any and all humidity through endless washing machine cycles, a neglected hall, tattered equipment, and Noga was lying there, trying to turn onto her side and sleep in her beloved fetal position, but the splitting pain woke her up, and again she lost consciousness. She could now hear the echoing melody of all those trapped by magical cords. Four hours had passed. A new shift started, new staff. Ronnie pleaded with the Head of the ward to let him in. The doctor didn’t understand a word he was saying, but he saw the desperation in his eyes and let him in.

Once they had finally allowed him through, he began patiently explaining to her: We went on a trip abroad. We rented a car. There was an accident. You’re in Naples now. In a hospital. Do you understand what I’m saying? She nodded her head. This routine repeated for the following few days, every day. She was getting better, she wasn’t in any danger anymore, and he rehearsed the story with her as though they were preparing for a TV show. Once he felt she was ready, he took her on a gameshow with prizes and all.

You know what your name is? Yes.

You know who I am? Yes.

She didn’t really talk but she replied with blinking, sometimes lifting her right index finger.

We went for a trip, right? Yes.

We had an accident, you know you’re in a hospital, right? Good.

You know where you are now?

In Jerusalem, she replied.

Jerusalem! He was excited for a moment: she spoke. It seemed like he’d finally made it, she was speaking, there it was – the first word uttered through her lips. He was relieved to begin with, and it took him a few seconds to be astounded by that word, “Jerusalem,” how it poured out of her as quietly as a slight pool of saliva assembling on a pillow beneath the loose mouth of a sleeping infant. What is that about? Why bring Jerusalem into it now?

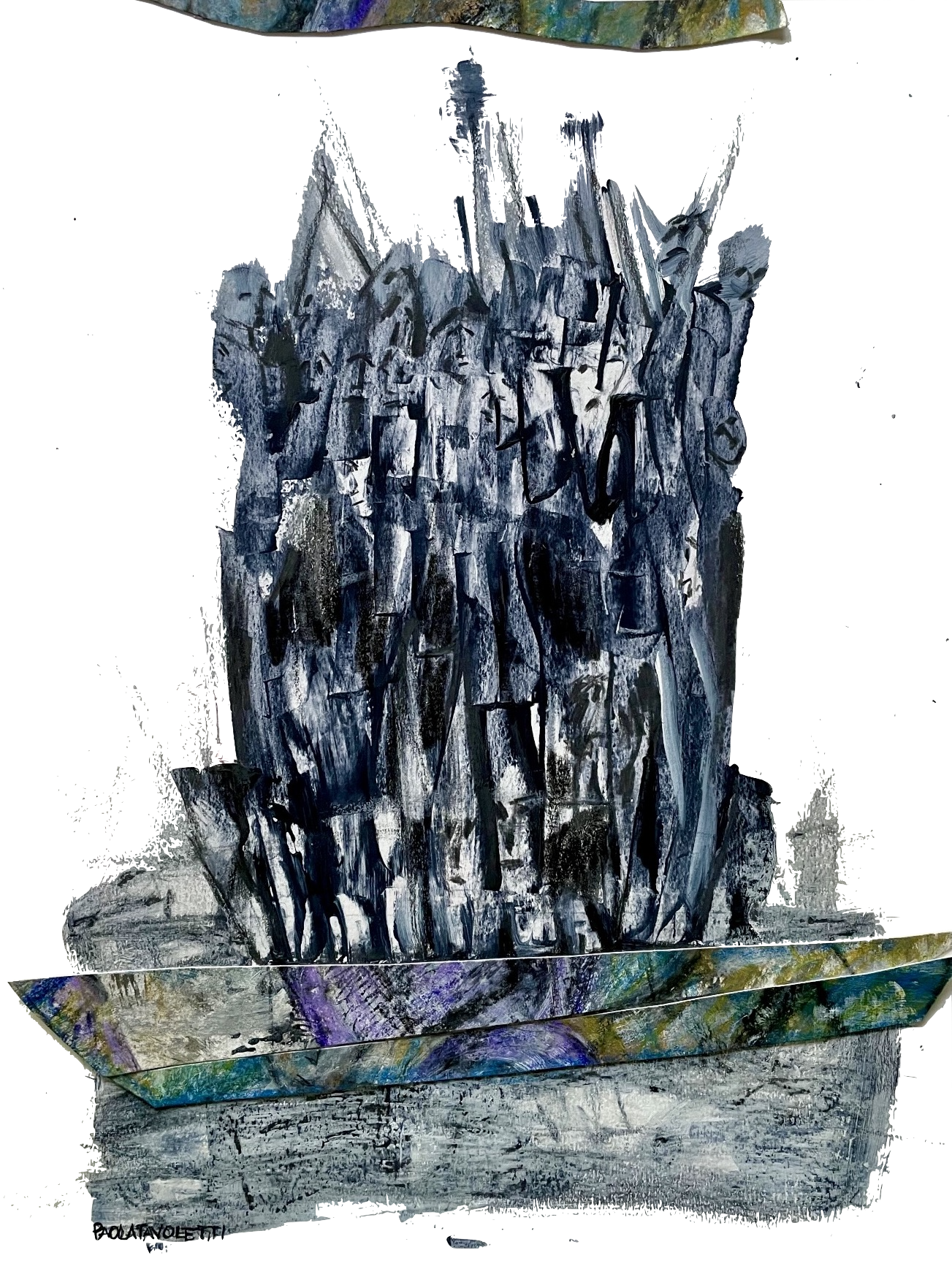

He knew that Noga, as well as her relatives or even extended family, had never lived in Jerusalem, not before they’d met and not since they’d gotten married ten years earlier. What is it with her? Is she going to come out of this mentally impaired? That really would be his ultimate punishment. He talked to her and shook her by the shoulders, what do you mean Jerusalem, you’re always cold in Jerusalem, don’t you remember saying that Jerusalem feels like Europe to you, always partly-cloudy, you said that you were a stranger in your own country’s capital, and you complained about how there were so many bricks in the walls that if someone were to take a single brick out then everything would fall apart and we’d be buried under huge piles of rocks in the streets? What do you mean Jerusalem? He wanted her to forget Jerusalem at all cost and at least say Haifa, her city of birth, but the head of the ward hurried over and shoved him away from her, reprimanding him in Italian, the ends of the words whipping their little tails at him, and forced him to leave.

But within her, Jerusalem was very clear to Noga, very lucid. All she thought was – hug me, love me, don’t say all that nonsense now, I want to live. Carry me away from here, I can’t find my way back, I can’t breathe here in all these dark warehouses.

Hey, you! Where did you go, she said to the anesthetist who came in to check on her. She didn’t have the strength to execute her speech, so it remained an internal monologue. The doctor noticed a physical restlessness. It was scary. She tried to sound light-hearted. You know that till this very day I still don’t know your name, please, talk to me.

He got up, and she followed him as he led her to Jerusalem. The voyage began in southern Italy, they walked a long way and reached Mount Vesuvius, trudged around it, treading over black volcanic earth, when all of a sudden Jerusalem appeared before them, flooded by soft light. It wasn’t the usual Jerusalem, the one you can only see through the clouds. Its golden domes shone blindingly, forcing the stare to lower down to the white-painted walls in order to handle the light. But anyone who didn’t look at the golden light didn’t suffer, on the contrary, it radiated a womb-like warmth. She recalled the note, where’s the note I’d prepared, I was supposed to bring it somewhere, don’t remember where, she was lost because she’d never gotten to know her way around the streets of Jerusalem, and she was frightened, her breathing growing heavier by the minute. A handful of tiny stars glimmered within the darkened, narrow, heavenly path into which she was plummeting.

Emergency! The doctors appeared and resuscitated her. Within fifteen minutes, her breathing stabilized and Ronnie collapsed onto the chair by her bed.

Noga seemed to think that the doctor was explaining to her about the recommended position for dying, petitioning her not to waste her dying moments. The minutes on the edge of death are more important than all of life lived, you need to use them wisely and die right. Die. You need to lie on your right hand side in Sleeping Lion position. Left hand over left thigh, right hand placed beneath chin, blocking right hand nostril. Legs out, slightly bent. To the right, a few delicate channels awakening the spirit of illusion. Lying on top of them and blocking the right hand nostril obstructs these channels and enables you to notice the glow breaking through during the moment of death. You should do it, Noga, that is the soul’s greatest wish. I too am waiting to witness that glow, I hope you’ll die.

The doctors performed the surgery as devout nurses tended to her.

And then, once her brain had been rattled and her life’s holiestelements plummeted out of her memory, she turned out to be in Jerusalem, of all places. She wanted to explain it as an illuminated revelation: All at once, the divine light of Jerusalem burst out of her. It was the ripe, golden afternoon light, fierce orange-yellow, spitting out sunrays. Her homeland stemmed from the light, and the children serenaded with their small, innocent voices, singing a church melody in pure canon, accompanying her all along the way.

She followed the man for hours on end until they finally reached the Kingdom of Jerusalem. They walked along the valley, numerous Jewish residences to their left – those without homes except for the caves within the rocks, where they lived as wild animals do. To their right they found the Siloam Tunnel, into which they descended down a set of stairs. Jerusalem, a beautiful vast city, despite the Saracens’ filth, so many of them crowding within it. The places where goods were sold were pleasant enough, streets bedecked with ornamental stones, tall windows illuminating everything. Above the arches were other streets, used for commuting from one residence to another. That was where the Saracens lived, since the Christians – the Order of Saint Thomas monks – as well as the Jews residing in the Holy City, were only allowed to live on specific streets. Once you entered the streets near the gate, there was a street to the right along which a man walked up until the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and there it split into numerous paths. All throughout the streets, linen weavers were sitting by the side of the roads, and above them the cooks, and from there appeared a street to the right crossing towards Mount Zion, where the Jews resided.

Up there was the first day of August and the sixth day of the week, which the Saracens deemed as holy – not because it was the sixth day of the week, but rather since it was the Day of Venus. Muhammad had admired Venus despite her immodesty, and therefore ruled for her day to be holy for all eternity. You could find excellent wine everywhere there, especially among the Christians, who had the best wine at a fairly cheap rate, and one Jew named Mordechai who could supply you with everything – he was the one Noga wanted to give the letter to, since Jews would always treat you faithfully, more than any non-Jew in the world. They reached Jehoshaphat Street. Her beloved walked on and she followed suit, like a shadow. Between Jehoshaphat Street and the city’s walls on the left were most of Jerusalem’s Syrian residents. There you could see the Church of Mary Magdalene and a little gate near it, through which you couldn’t come out to the fields, but would instead have to walk through two tall walls. From that gate he led her to House Kiva at the top of Mount Zion, seven-hundred and thirty steps away. Noga realized that he was leading her the right way. They reached a closed gate, through which the holy woman had passed when she’d brought Jesus to the temple. There, in that place, he excitedly explained to her that further up, westbound, was a place called Kree’at HaGever, where Saint Peter’s denial of Christ had occurred and where he came out to weep. The spot where he’d wept was a hundred and eighty-seven steps away from House Kiva. Seventy-six steps away from there was the street of the Jewish synagogue, leading all the way to the arched streets.

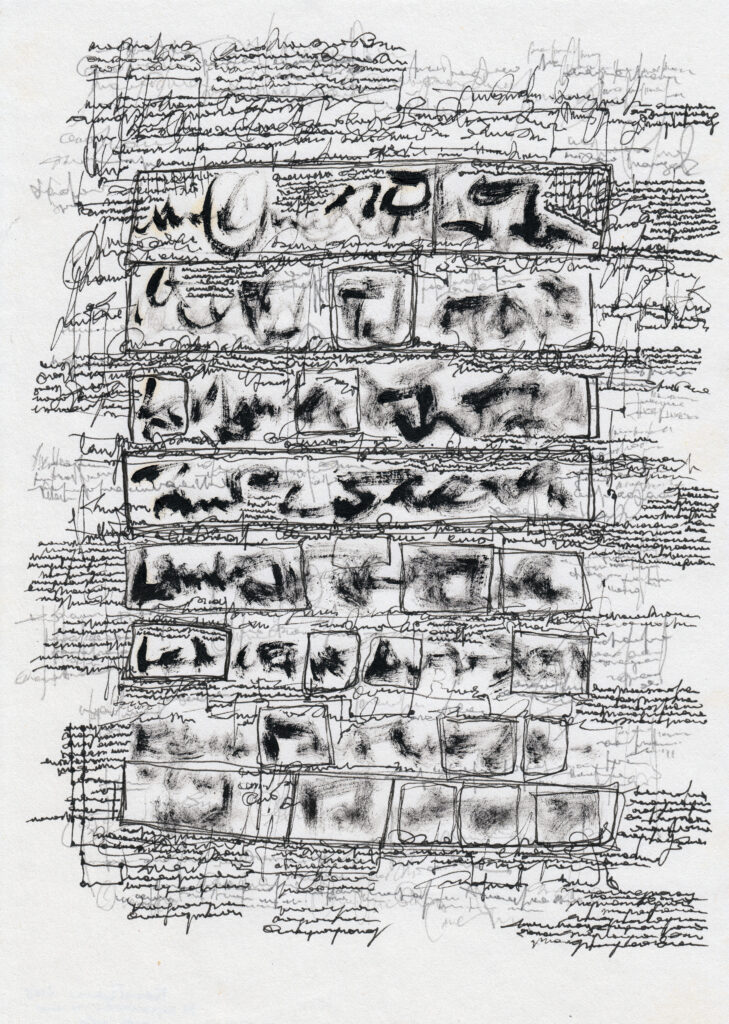

Dottore, Noga said, don’t worry, I remember that I’m Jewish. I’ve been to the Wailing Wall. When I neared its bricks, I heard a growing hum and slowly realized that the sound was internal and not external and I hid and gently leaned against the holy stones and all the notes crammed into the crevices while the hum got stronger. I don’t how but I suddenly realized that I needed to leave, and even though I nearly fainted, I had to get away from the bricks, and it was only when I’d managed to disconnect from the wall that the hum slowly ceased and the faintness and the daze dissipated and I regained clarity. But that was down below.

There, in the Upper City, they kept walking in order to get to the holy temple. What are those songbird sounds, she asked and he put his finger on his lips and hushed her, just listen. The yard was nicely tiled, white marble. The Saracens kept it clean. They’d enter it in reverence, only ever barefoot, kneeling down and kissing it endlessly. They didn’t allow Christians to enter the yard or the temple, nor Jews, whom they viewed as dogs, non-believers. Solomon’s Temple, along with the structure in front of it, spread ahead all the way to Miriam’s residence. Those two temples were immensely honored by the Saracens, illuminated by countless lamps which shone day and night. If a Christian were to be found there, he’d be sentenced to die on the spot or convert.

Noga followed him all the way back. She now realized his intention: not Capri, but rather Jerusalem. Up until that moment, she’d felt like she was inside the darkened warehouses of an industrial estate, rusty staircases and water dripping from the ceilings. Cold water. Each drop an unpleasant surprise. There was a ruckus of pistons or owls, her feet bumped into pieces of junk and remnants of bricks and darkness. Until she finally managed to speak and replied, “In Jerusalem.”

Dorit Silverman nominated as vice president of the Hebrew Writers Association since 2015 and she is the head of the board of the literary magazine “Moznaim”. She has published 21 novels – some of them searching for the Jewish identity, others – for the feminine identity and for the meaning of motherhood. Silverman got her PHD for Literature on 1990. She took part in some international conventions. One of her novels adopted into a

movie, and two others – into a manuscript and on the process to become movies. Her books were translated in to several languages, and received several scholarships, awards and grants, such as:

The Tel-Aviv Foundation for Art and Literature.

The Dov Sadan Foundation.

New York Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture.

The Israeli Film Fund, Grant.

The “kugel” Award for literature.

The Prime Minister Award, 2017.

Dorit Silverman has three children: Tom, Dean and Avigail.