China Dolls

J.C. Henderson

I

My memory of mimosa trees

is forever overlapped

with men carrying exotic birds

in gilded cages, covered

with heavy black cloth

to fend off the noisy world.

Almost like that,

my father carried

me, enclosing me

in his overcoat—the foggy

autumn was chilly—a layered

cheese-cloth mask

over my face, just below

the eyes, so I could see

the mimosa trees, dotted

with magenta flowers

shaped like lanterns, thin

petals curled inward, the way

my small fingers clutched

my father’s shoulders.

The legend said, “A daughter

was a pearl the father held

to the moon. ” He hid me

in his pocket. I climbed

and scratched like a cat.

II

Cherries, dark, red, bloody

mouthfuls, about to burst.

I wore

your makeup,

coy

in my 15th

birthday dress my father

bought me.

We became a three-some

of hunger—

the red cherries

on empty stomachs

made us sick, taking our blood

for a ride, undoing

its color. As you, Mommy,

undid the seam

of the birthday dress: “you are

a good girl,

but not pretty.”

I tore

your words apart, played

scramble games

I would never score, until

each word became

a tigress, or

a pawn, or

a pet.

You must have some

such thing, too, Mommy—

is it the scar

on your belly?

III

In my childhood eyes,

my mother was

a beauty, except when she was

a bull, her sudden rage

and strength overpowering

my father’s.

She had been a broken China

doll when my father met her.

He mended her

and built a makeshift

of a wife.

Such mending and building

would become the story

of their lives.

And mine.

In her 80s now, the China doll—

never whole—is spared

from the patchwork, and most of all,

from remembering.

Afternoons, she serves him hot tea

like the good wife.

And me.

J.C. Henderson is a writer as well as an artist. She publishes visual and poetry in literary reviews and poetry magazines. Her work has appeared, or forthcoming, in journals such as Fourteen Hills, Freshwater Review, Ellipsis, Suspended Magazine, Poetry East, Sunspot Literary Journal, The Comstock Review, The Clackamas Review, and SLANT, to name a few. Henderson explores the topic of who we are as humans, mostly through telling personal stories in her poetry.

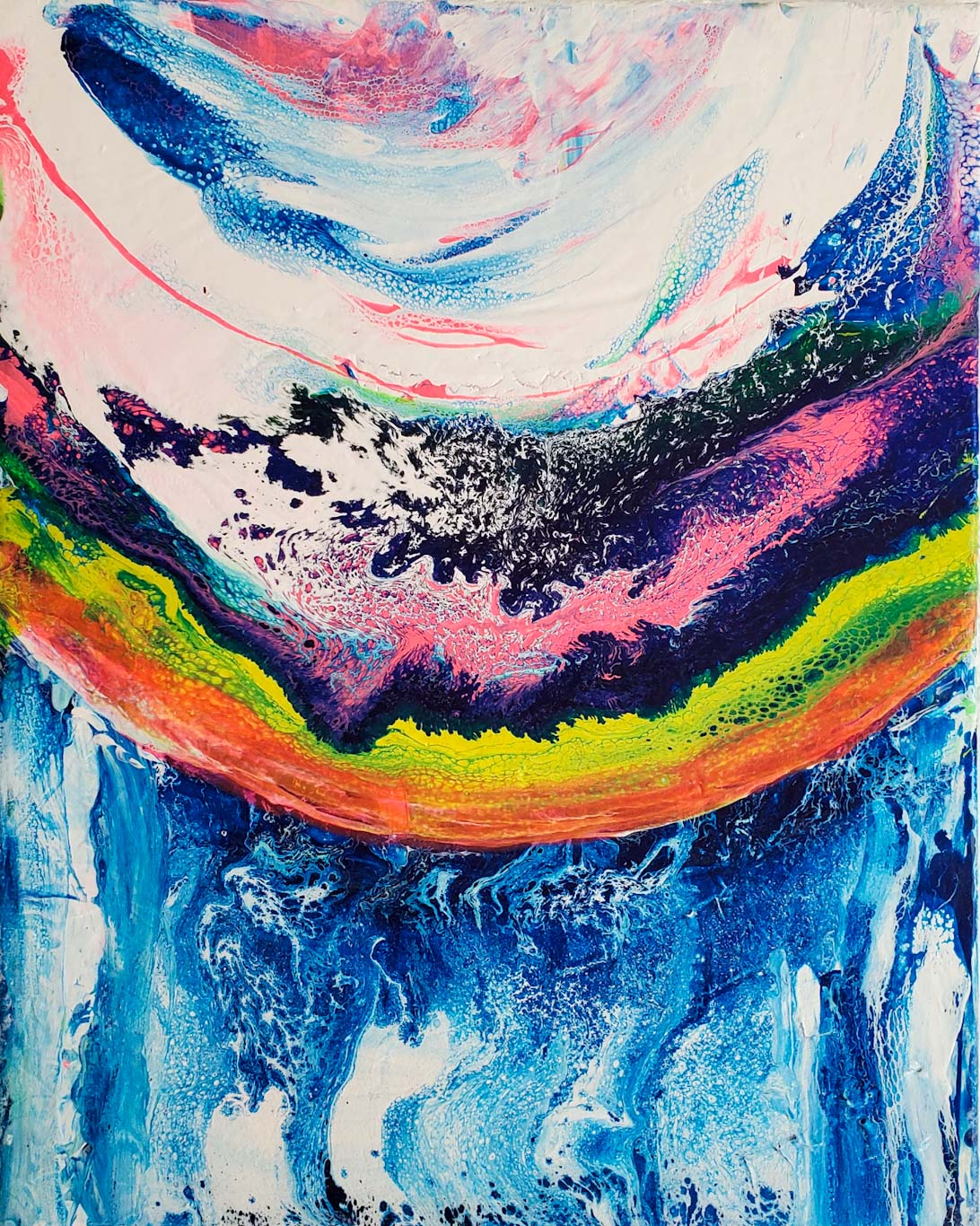

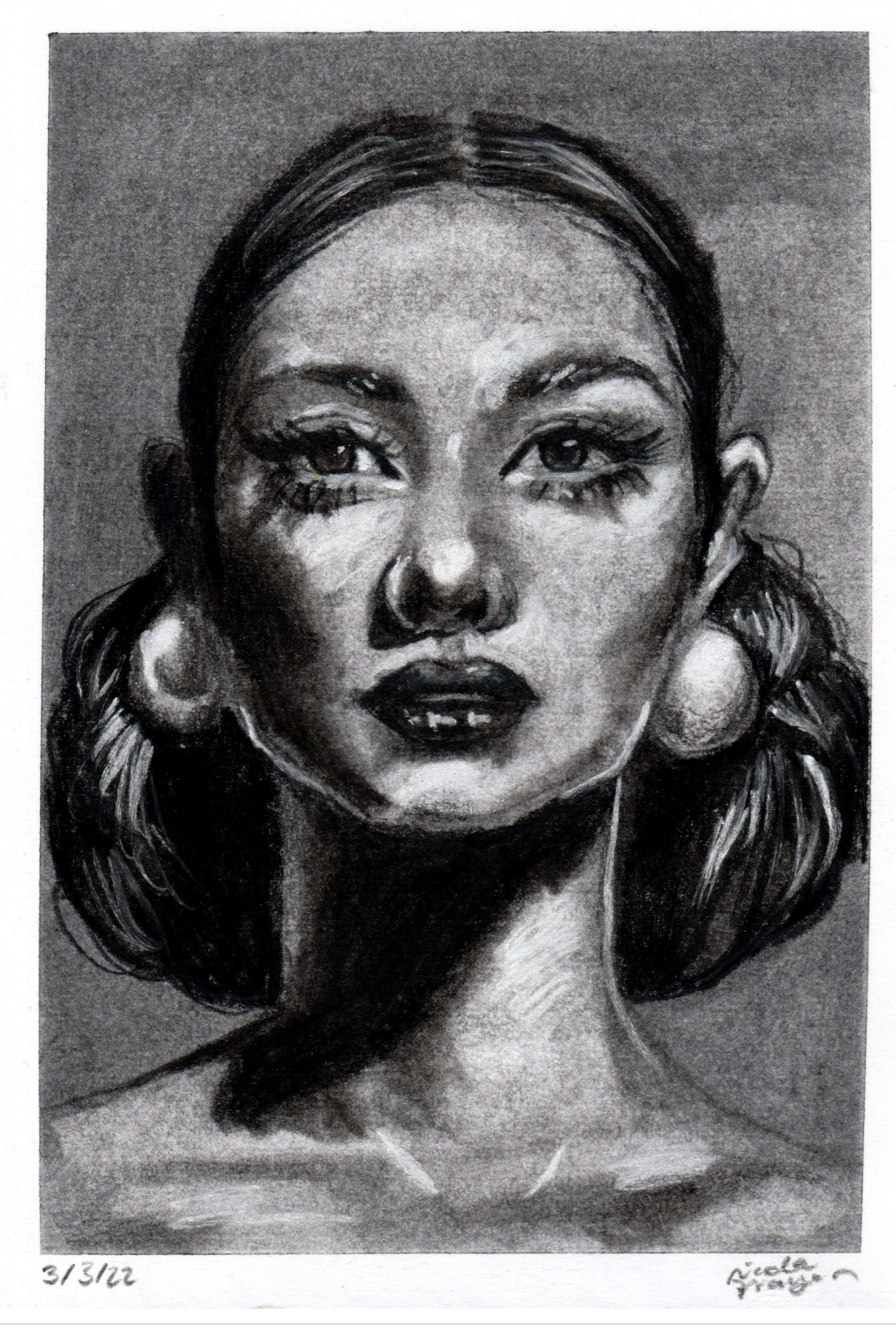

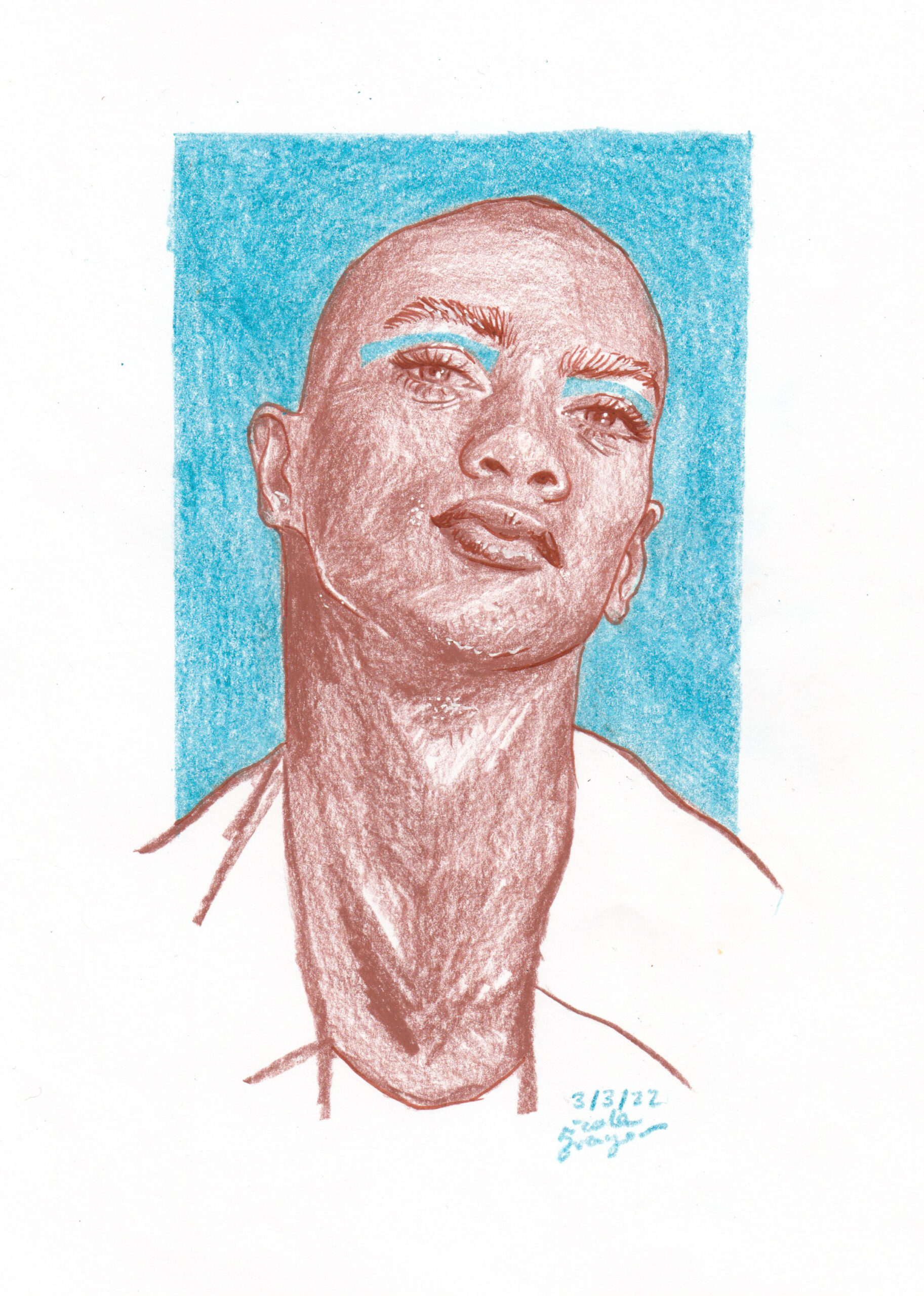

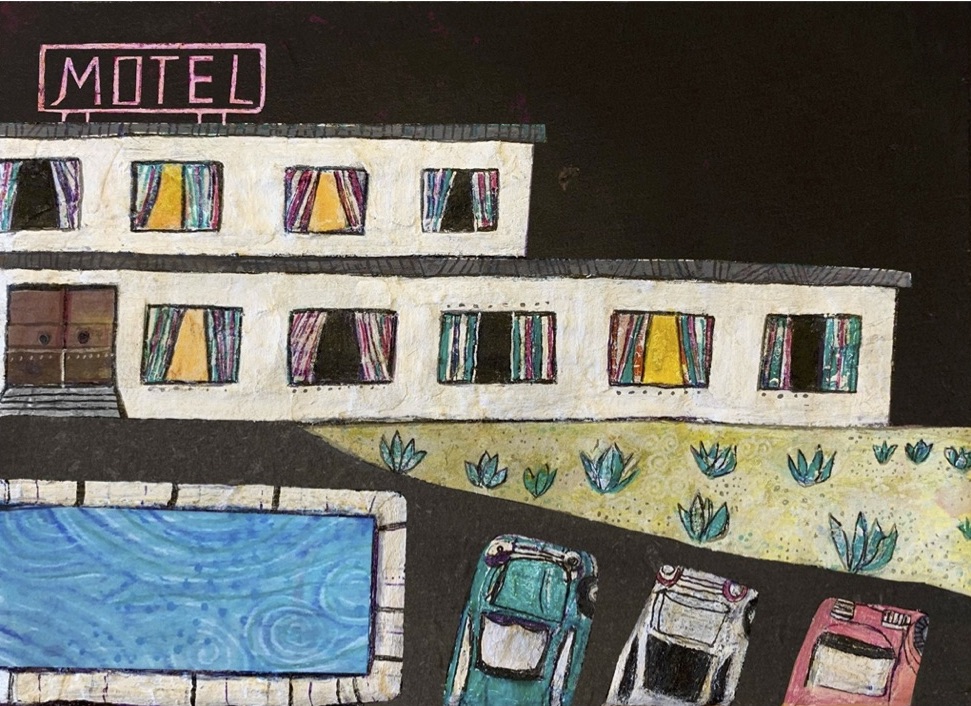

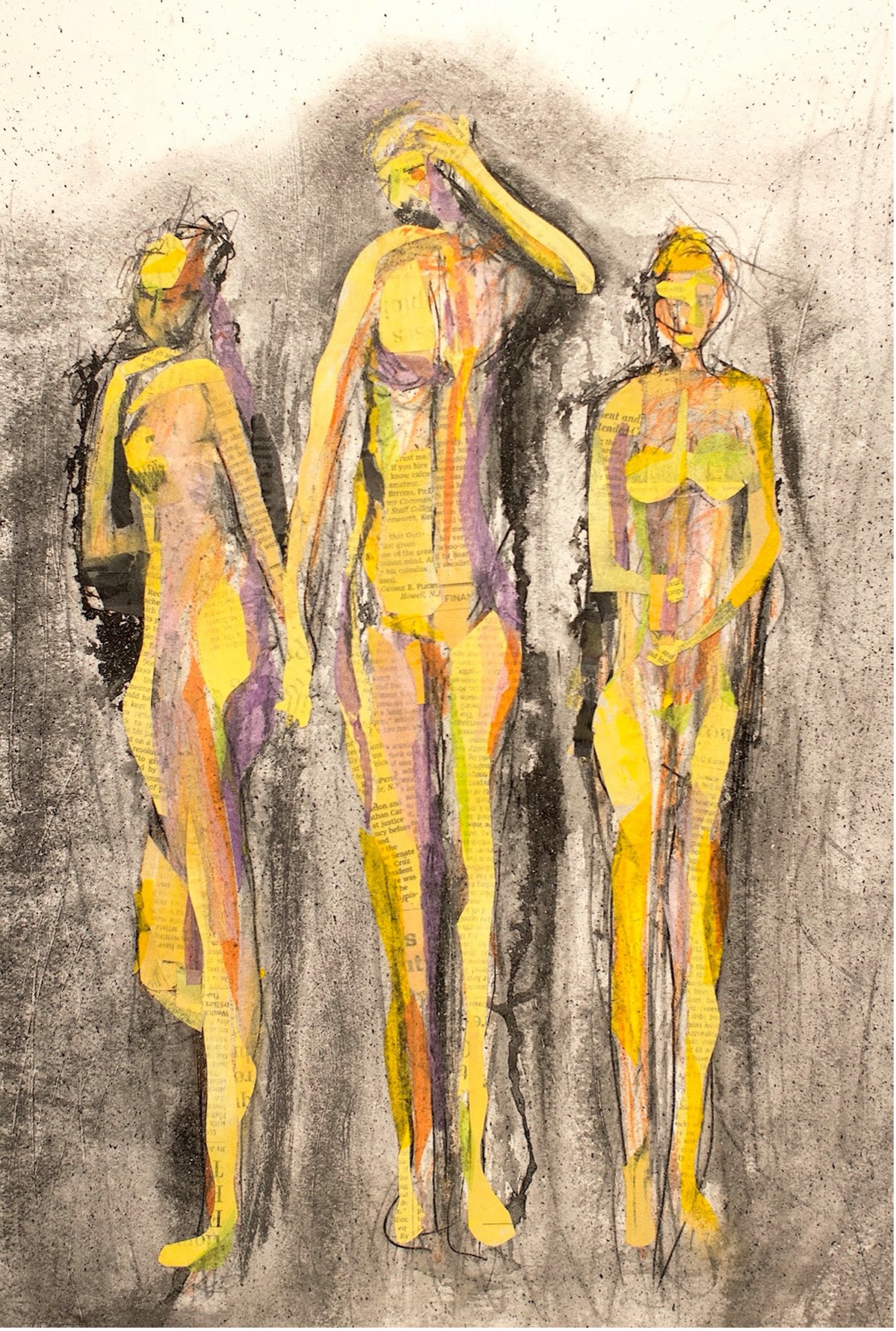

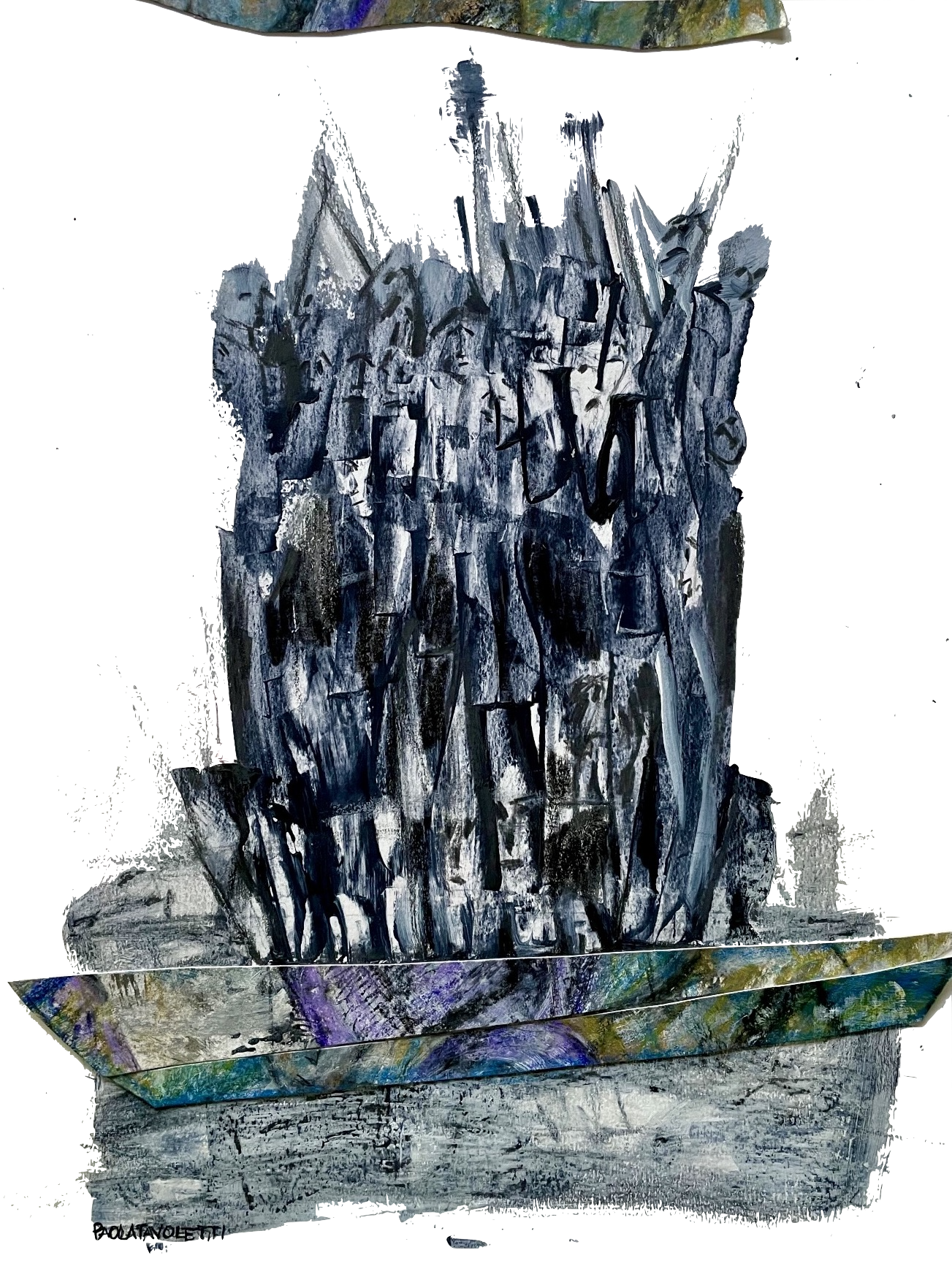

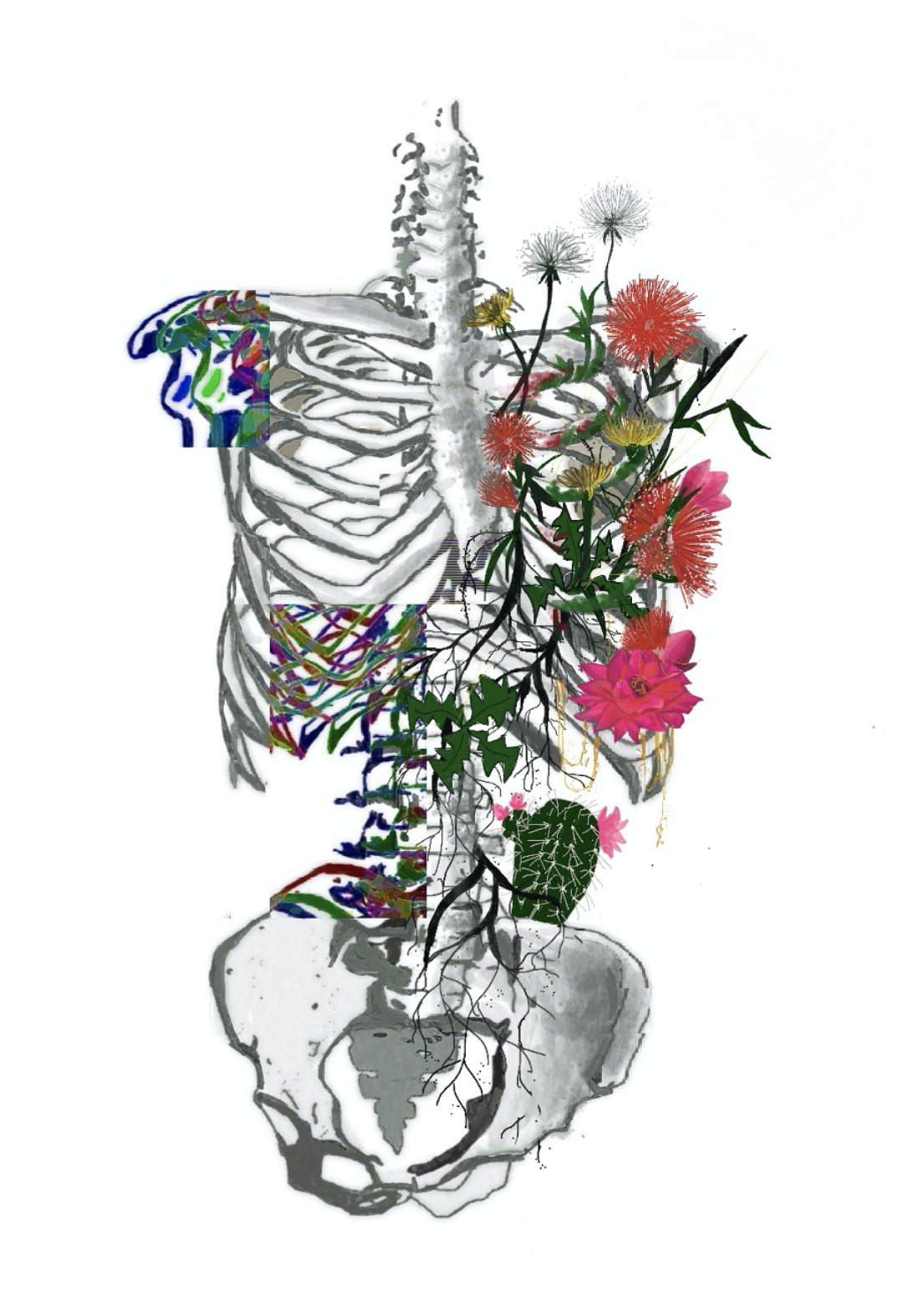

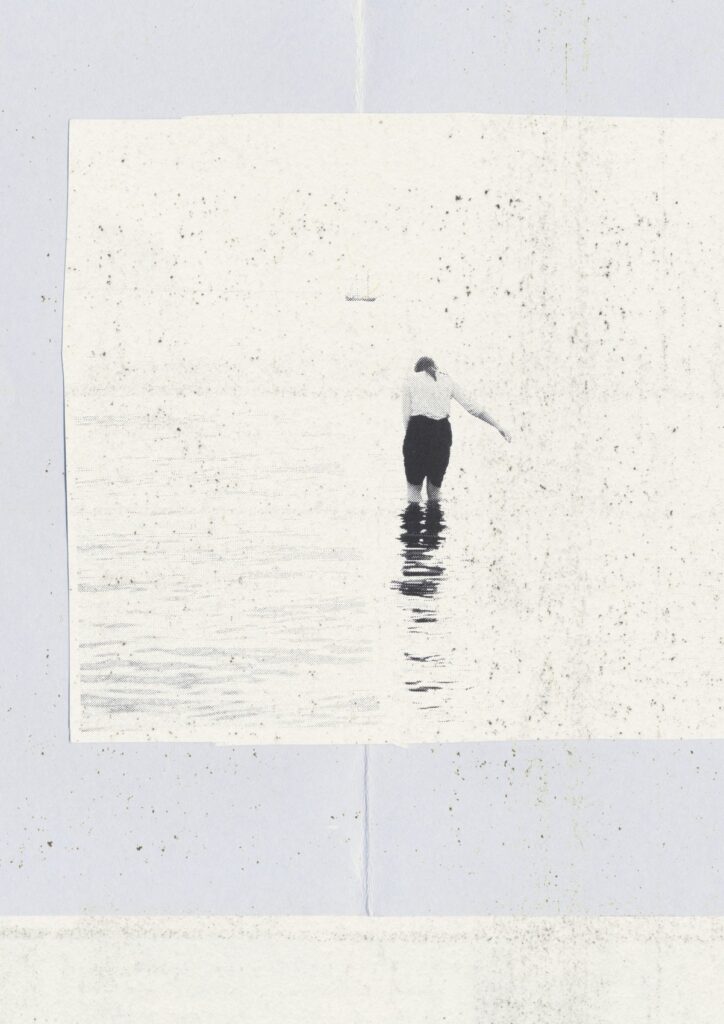

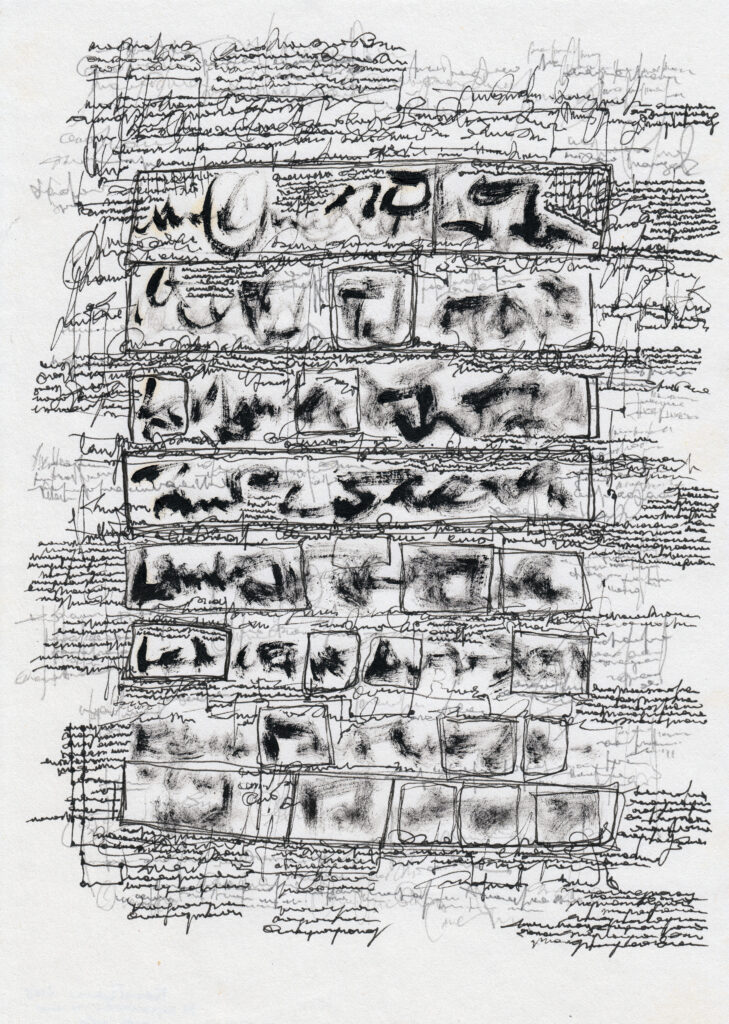

Art: Time-stressed by Uzomah Ugwu, who is a poet/writer, curator, editor, and multi-disciplined artist. She is a political, social, and cultural activist. Her core focus is on human rights, mental health, animal rights, and the rights of LGBTQIA persons.