The Buzz

by Carl Boon

The experts’ predictions were wrong. The buzz arrived months earlier than they’d expected.

Mother, ironing in the kitchen, noticed it first. As usual, she had the radio tuned to 1590 WAKR, and mistook it initially to be mere static. When she realized what it really was, she called us in one by one to announce its arrival, thinking she could handle us more effectively that way: first my sister Charlene, then Carla Mae, then me. “You’ll just have to stay calm and be a big boy now,” she said, then hurried to the stove to put the finishing touches on her casserole. She didn’t say it, but I knew she was afraid that it carried with it some nasty unrecognizable that would get into the food. The oven was safer. The open air was iffy.

Carla Mae was the next to hear it. She’d gone upstairs to make phone calls—the first obviously being to her idiot boyfriend Ralph—and according to her it was inside the phone and quite prominent there. Immediately she felt like taking a shower, believing the water and the steam could settle it down or even render it indistinct. She was wrong. It liked water. “It seemed to stick to it and assume its liquid energy,” she told me later that night, and I believed her because it came to me when I was brushing my teeth.

The only one of us who didn’t hear it in the first twenty-four hours was Charlene. Mother thought her good fortune could be traced to the fact that she hadn’t begun menstruating yet, and to me that sounded plausible. Perhaps it feared young girls or simply decided to wait them out. See: already, even on that first day, we believed the buzz could think, even though weeks earlier WAKR had informed us that was unlikely. If it could think, well, that would be disastrous and perhaps unholy. This all happened on a Saturday, and the next day Father came home a day early (back then he was overseeing a construction site in Muncie, Indiana) to accompany us to church.

Church, we surmised, would constitute a refuge. If the buzz could think, it wouldn’t want to do so around Jesus, or at least that’s what we thought. During Reverend Lindley’s sermon, however—just as he was speaking of children in regards to Matthew 11—the choir members began clutching their ears, and in less than a second I knew it was there too and could even penetrate the walls of God. No one stayed for coffee and doughnuts that Sunday after the service; most stopped at Lowe’s or Home Depot to supply themselves with what they thought was necessary to keep the buzz away: plywood and insulation, thick panes of glass, industrial-weight aluminum foil, but their preparations, though well-intentioned, came to little. The buzz was not a hurricane. It was a buzz, and would be here to stay.

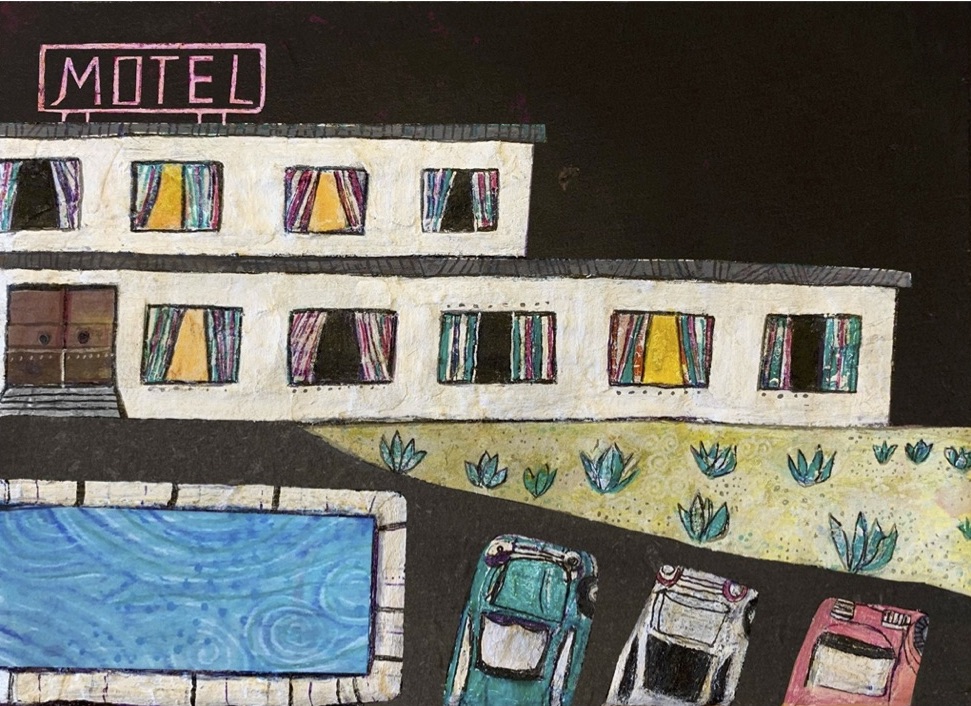

Strangely enough, some people actually liked it. They said it helped them sleep or enhanced their appetites, but for most it was simply an annoyance, like summer flies or the whine of a vacuum cleaner in an adjacent apartment. Others it hit hard, rendering them helpless or incontinent. Toilet paper sales skyrocketed and the region’s counselors got rich. Schoolteachers and accountants seemed to be the most affected, at least according to the Beacon Journal. Most of them stopped coming to work altogether. On the contrary, postal workers and bartenders appeared not to be affected at all. The times the buzz reached its peak for some, mail delivery sped up and the taverns filled up too, sometimes even before noon. My Uncle Mike, who managed Zippy’s Microbrew on Market Avenue, loved the buzz. Business had never been brisker.

No one knew what to do about it, save accept it as something that would always be. Like Christian Conservatives, I supposed, or rabies. No one got nauseous from food, cooked or raw, and no one (at least that I knew) suffered any side-effects. Sure, we heard stories of people in Geauga County growing weak with diarrhea, folks in Ashtabula vomiting forth walleye dinners, and the Amish down in Millersburg suffering from periodic bouts of gout and insomnia, but they lived counties away and were probably immunocompromised to begin with. I got used to it, just like Charlene and Carla Mae and Mother and Father, and discovered one Wednesday in December that Billy Joel’s “Uptown Girl” seemed to negate it, quiet it. But it was only that song and only when played at a certain volume. (It loved Bon Jovi and Aretha Franklin. Who knew why? It remains a mystery.)

I was eleven years old when the buzz first arrived. I’m 45 now, and it’s still with us. It seems to dissipate in October when the weather begins to cool and the nights grow longer, peaks on the New Year, then settles down until around April. Summers are traditionally the worst, particularly the 4th of July and Labor Day. We’ve come to understand it loves fireworks and cookouts. All in all, however, we’ve learned to live with it. WAKR plays “Uptown Girl” at least seven times a day, my parents are dead, and my sisters both live in Nebraska with their families, the last state that’s (so far, anyway) immune to it. I’m a holdout. Buzz or no buzz, I’ll never leave Akron. I was born here, and I suppose I’ll die here too.

Carl Boon is the author of the full-length collection Places & Names: Poems (The Nasiona Press, 2019). His writing has appeared in many journals and magazines, including Prairie Schooner, Posit, and Washington Square Review. He received his Ph.D. in Twentieth-Century American Literature from Ohio University in 2007, and currently lives in Izmir, Turkey, where he teaches courses in American literature at Dokuz Eylül University.