Red

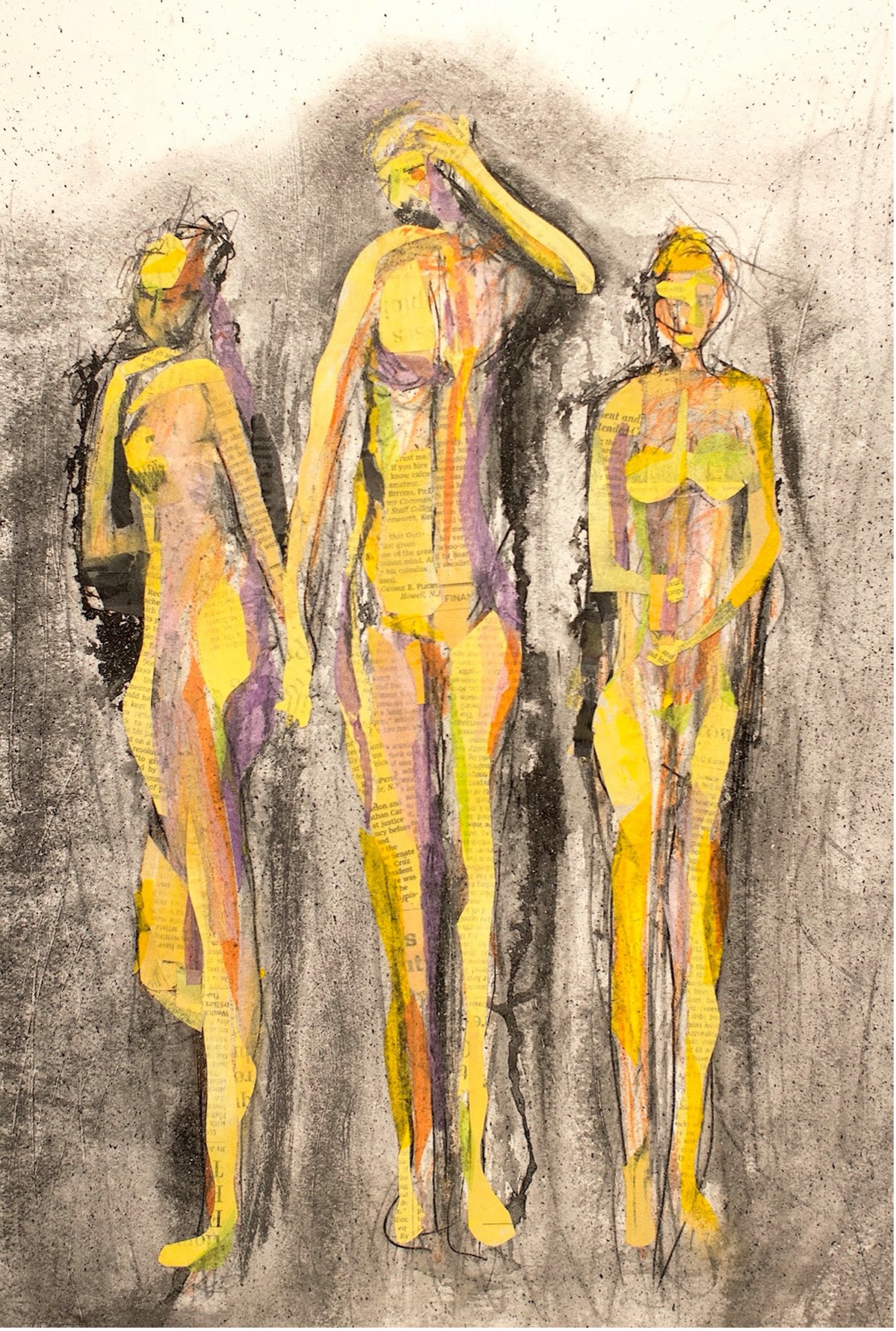

by Diana Norma Szokolyai

Red

I.

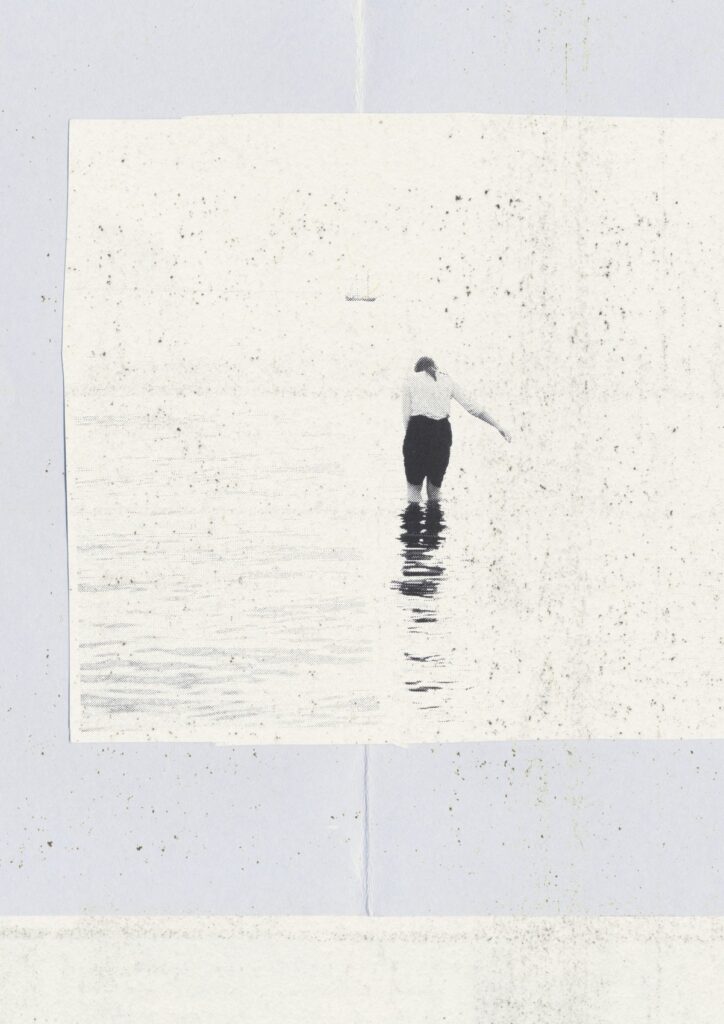

There is a red ball that fits into the palm of my hand. I am three years old, living in the village on the outskirts of Budapest. It is one of my favorite toys; the little white stars on it are something I can reach, unlike the starry night above the ocean that separated me from my mother. The dots and stripes have a pattern, and I run my fingers along and count. I have already endured separating from my father, my mother, and soon, I will be separated from my maternal grandmother and grandfather, Mamuska and Papuska, with whom I was living, and to whom I had grown greatly attached. I clutch that red ball, throw it against the kitchen wall and let it roll back to me. This is my redball. I left it behind when they came to take me back to the land of stars and stripes, when I left the language that I knew as home and walked, wide-eyed and longing, into English.

II.

We are at an airport before a long goodbye, and my father gives me a little teddy bear in a red and white polka-dotted dress. I am four years old and name her “Maci,” meaning “teddy” in Hungarian. Maci has a red bow on one of her ears. I talk to her every night before my prayers, holding her up with my arms while I lay back on my pillow with my braids. I have no siblings yet and will remain the only child of my mother and father, as they go their separate paths, eventually never to speak again. Maci is my sister, my confidant, and her red dress with white polka dots enchants me. Her dress is a sweet raspberry red, and it reminds me of the color of málna preserves my grandmother makes in the summer. Her smile promises so much, and I do not hesitate to hug Tenderness and Comfort. I reach for this, as each child does when they snuggle their stuffed animals in the dark.

III.

In the sandbox created for me in the Hungarian courtyard, outside my Mamuska’s townhome built for railroad workers, my small hands love digging holes. My Papuska comes out, sits next to me, and asks me where I am digging to. I shrug. Then, he tells me that if I dig deep enough, I will dig all the way to China. I imagine digging a tunnel long enough to crawl through and come out the other side. In my dreams, I crawl from one red country to another, with no passport, carrying nothing but my searching heart and an acorn in my pocket. Papuska taught me to collect them on our strolls. To think they held the treasure of a tree inside them, and I kept one that we collected in my heart-shaped porcelain jewelry box for years after he passed away. All the potential of a tree collected by a grandfather who has now crossed over, resting quietly in a little girl’s white porcelain box with gentle flowers painted on it.

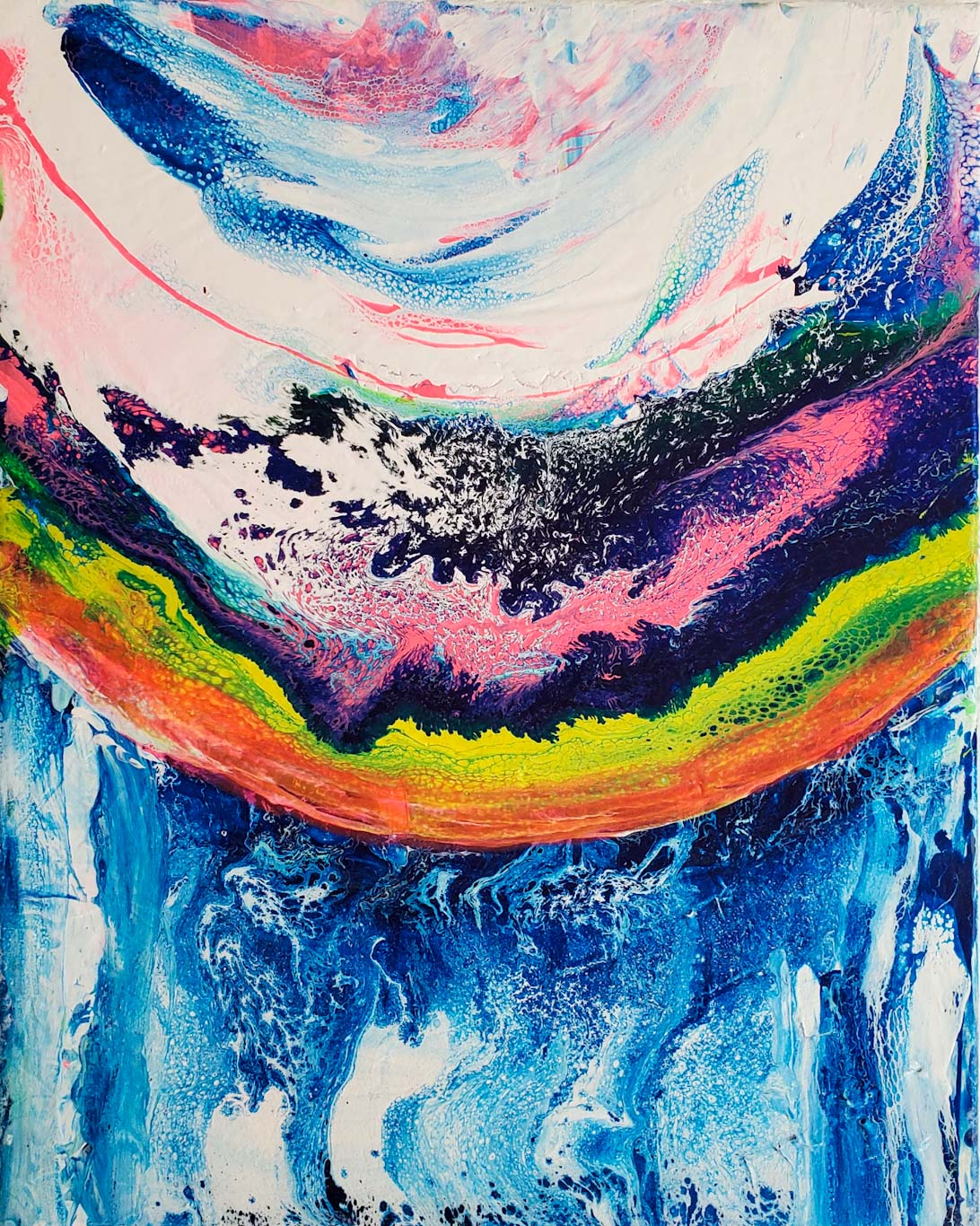

IV.

Hungarian Red—who knew it is the name of an actual color? Several years ago, someone showed me a Renaissance Revival ornate ring with a red coral stone; they called it “Hungarian Red.” Hungary has no sea coral, but it has paprika with a striking orange tint, like my Mamuska gets from the open-air market in Szarvas, sold by the farmer himself. A treasure of the sea, the color of a landlocked country’s iconic spice. A delectable color. I wonder who first named it “Hungarian Red?” I cannot easily find the answer, though I search. I can speculate that perhaps inspiration was taken from either paprika or the tulip flower. I grew up seeing beautiful red tulips on folk art embroidery all over my grandmother’s house and in those of her friends. The tulip is a popular flower in folk art imagery, wood carvings, paintings and embroidery. My grandmother is a folk artist who has had her embroidery in shows. The red thread pops out at you against the delicate white cloth and makes you want to celebrate life.

V.

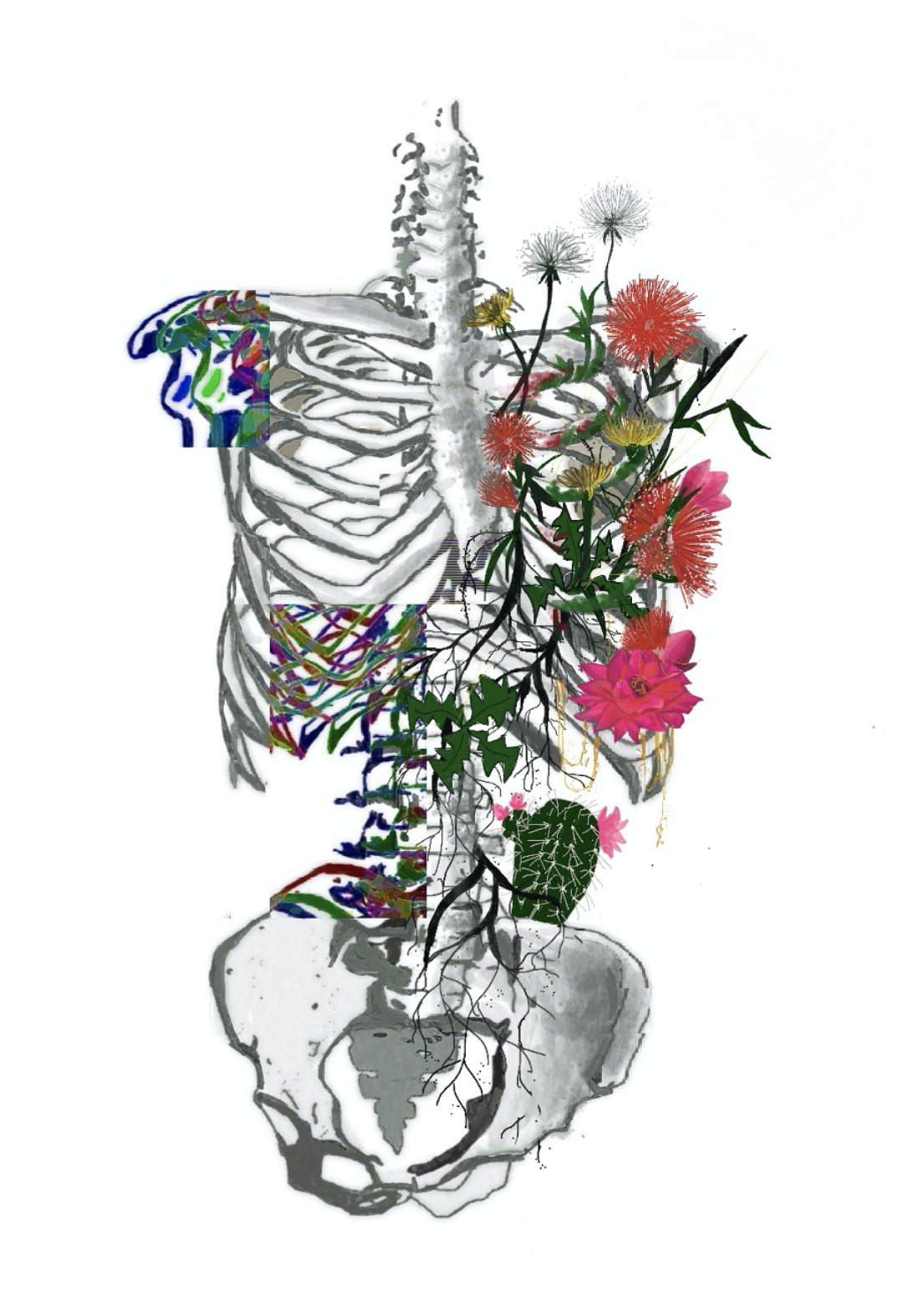

And Blood. I feel I am swallowing melted iron while in a room with iron curtains, smelling the tawny rust all around me. My tonsils have been removed. I’m about four years old in a hospital bed with the pale Communist Green paint closing in on me. I’m one patient among many, all in rows in a large open room, our beds close together. My linens are white, the sheets are thin.

I am in a chair, and they put a gas mask over my face. They say I will go to sleep quickly. I try not to sleep. I am fighting the sweet flavor of the gas, telling myself “No, I will stay awake.” There is a Communist Yellow, kidney-shaped bowl next to me, a receptacle for spit up blood. The corruption of the communist state had washed every vivid color in the hospital to a chalky, pastel version of itself. The air is heavy with the gray breath of lies and bribes, even in a place of recovery such as a hospital. Nothing is transparent, everything is stacked. My mother is an ocean away working three jobs. My grandparents slip the Hungarian doctors American dollars from her in hopes they’ll give me better care. They visit me and bring me forbidden sweets. They think this tonsil removal will be the solution to my breathing problems. They don’t yet know that I have asthma or that I am allergic to milk. The taste of blood in my mouth is awful.

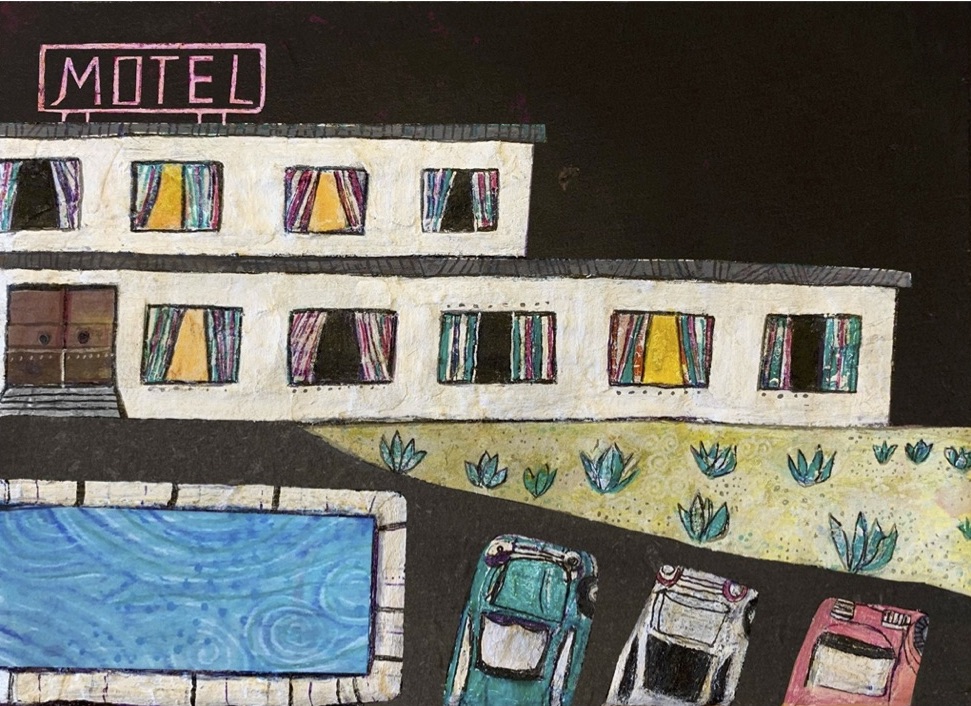

VI.

I had a red and white wooden furniture set in my childhood home in America. It was white painted pressboard with red knobs. With my neighborhood friend, I had written a secret message in red crayon underneath one of the drawers, “best friends forever.” When I would leave the country to study abroad in college, my younger siblings moved into my room, and that furniture went into storage in my aunt and uncle’s basement. I’m not sure what became of most of that stuff, over two decades later. To think of some of my childhood stuffed animals, letters, and other possessions sitting in a basement for years. The materials that surround us for decades may be reduced to sawdust, but we remember the feeling they created around us. Who does not remember a favorite childhood place, a corner of their room they used to hide in, the way they set up their dolls on their bed, or where they kept top secret notes and letters tucked away? I didn’t leave Maci in that basement—even as a twenty-year-old, I couldn’t. I kept Maci with me, along with two other precious toys, in an old hatbox. When my child was four, I presented Maci to him, and he adopted her. The color of red on her dress may have faded, but her smile still promises Tenderness and Comfort, now, to my son.

The Red Thread continues to weave many stories through my life, and now you have heard a few.

Diana Norma Szokolyai is a poet, writer, and educator. She is editor of CREDO: An Anthology of Manifestos & Sourcebook for Creative Writing and the forthcoming Disobedient Futures. She is also the author of the poetry collections Parallel Sparrows and Roses in the Snow. Her writing is published in Critical Romani Studies, The Poetry Miscellany, The Boston Globe, Up the Staircase Quarterly, VIDA: Women in the Literary Arts, Quail Bell Magazine, Luna Luna Magazine and MER VOX Quarterly. Her poetry & music collaborations have hit the Creative Commons Hot 100 list and have been featured on WFMU-FM. Her poetry has been anthologized in Other Countries: Contemporary Poets Rewiring History, and Teachers as Writers, as well as translated into German for the anthology of Romani poets from around the world Die Morgendämmerung der Worte, Moderner Poesie–Atlas der Roma und Sinti. Her poetry has been shortlisted for the Bridport Prize (UK) and has received honorable mention in the 87th Annual Writer’s Digest Competition. She has collaborated with composers from around the world, recording her poetry with the following musicians: Sebastian Wesman (Estonia), Dennis Shafer (US), David Evan Krebs (US), Jason Haye (England), Etienne Rolin (France), and Teerapat Parnmongkol (Thailand). She is Co-Founder/Co-Director of Chagall Performance Art Collaborative, an arts organization that builds community around the interdisciplinary arts with a gallery and workshop space on Artists’ Row in Salem. She is also Co-Founder/Co-Director of Cambridge Writers’ Workshop, an organization that leads writing retreats in France, Spain, and the US. A first generation American of Hungarian Romani heritage, she holds an MA in French from UConn, an Ed.M. in Arts in Education from Harvard, and an MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She is on currently on faculty at Salem State University and Harborlight Montessori School.