Land of the Invisible

by Allie Dixon

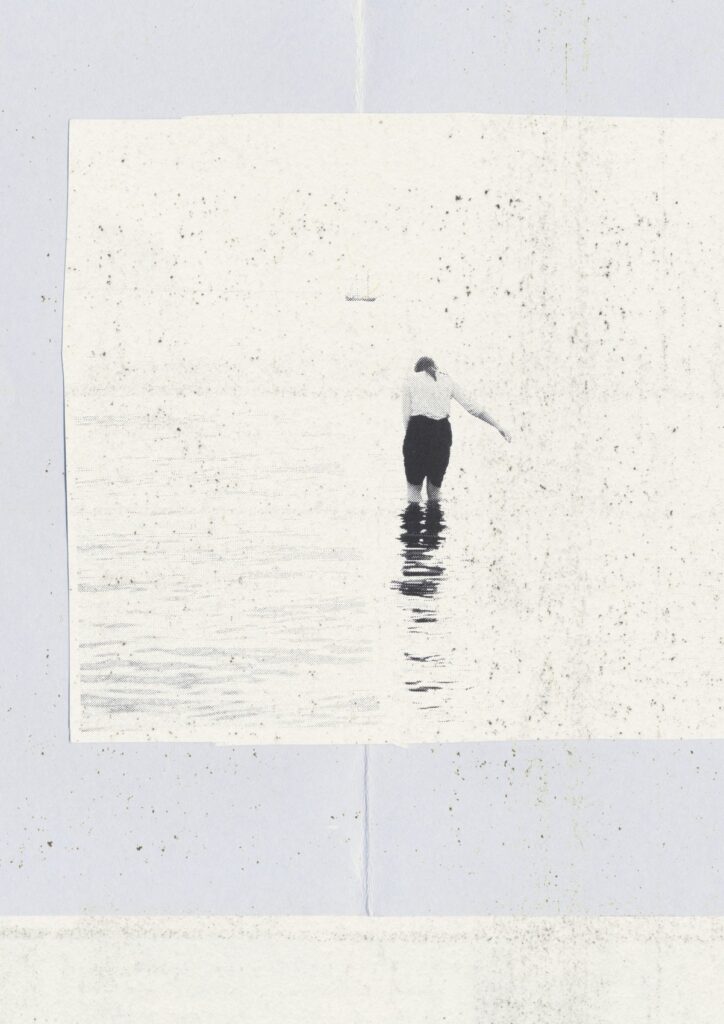

My great grandfather, Rudolph, my Pépé, painted landscapes. I never met him in the flesh, but I saw him paint in the middle of the night, sitting on a stool with his easel in front of him on my grandparent’s screened in porch long after he was dead. I’d see his wife, my Mémé, Olive, too. She’d walk out onto the porch after him and disappear into the night. I always imagined she was walking out to look over her husband’s shoulder, maybe playfully critiquing his work. I never saw her long enough to witness anything else other than her gliding through the dark into nothing. But Pépé stayed long enough for me to observe. Sometimes, he’d wink at me. He had high, handsome cheek bones and a long, pointed, French nose, like mine. Then, just like Mémé, he’d vanish into the night, like someone pulling apart gossamer until it was so thin that it became invisible.

When I was a little girl, I slept at my grandparent’s almost every week with my older brother and sister. I slept in the living room on a mattress next to my brother. My sister slept in my mom’s old room in her own bed. She was the oldest, four years older than my brother and five years older than me, so she usually got her own space. But I liked sleeping in the living room on the floor. It always felt like an adventure even in some place familiar. The living room was next to the raised, screened in porch where I saw Pépé. It was right next to my grandmother’s bedroom in case I needed her, and it was also next to the hallway with the French doors, always opened, that my grandma used as a sewing room. Every space was attached together by the thick timber lines of the wooden ceiling beams that looked so heavy and like they were floating up against the ceiling at the same time. I saw a lot of gossamer figures emerge and enter from the open French doors, somewhere from the dark sewing room hall, but I only really recognized Pépé and Mémé. I’d seen pictures. But even if I hadn’t, I would’ve known they were family. Something in me, heavy, sturdy but also light and connected just like the ceiling beams told me so. It connected us. It was as if Mémé knew to wait until I was perfectly awake, not alert, but not groggy, just peaceful in my breathing and wondering about the world in the dark, resting in a space of waiting and knowing she’d come, in a space better adjusted to see what I felt during the day but lacked permission to access. As a little girl, these nights, this space, it was my most secret and favorite part of being alive.

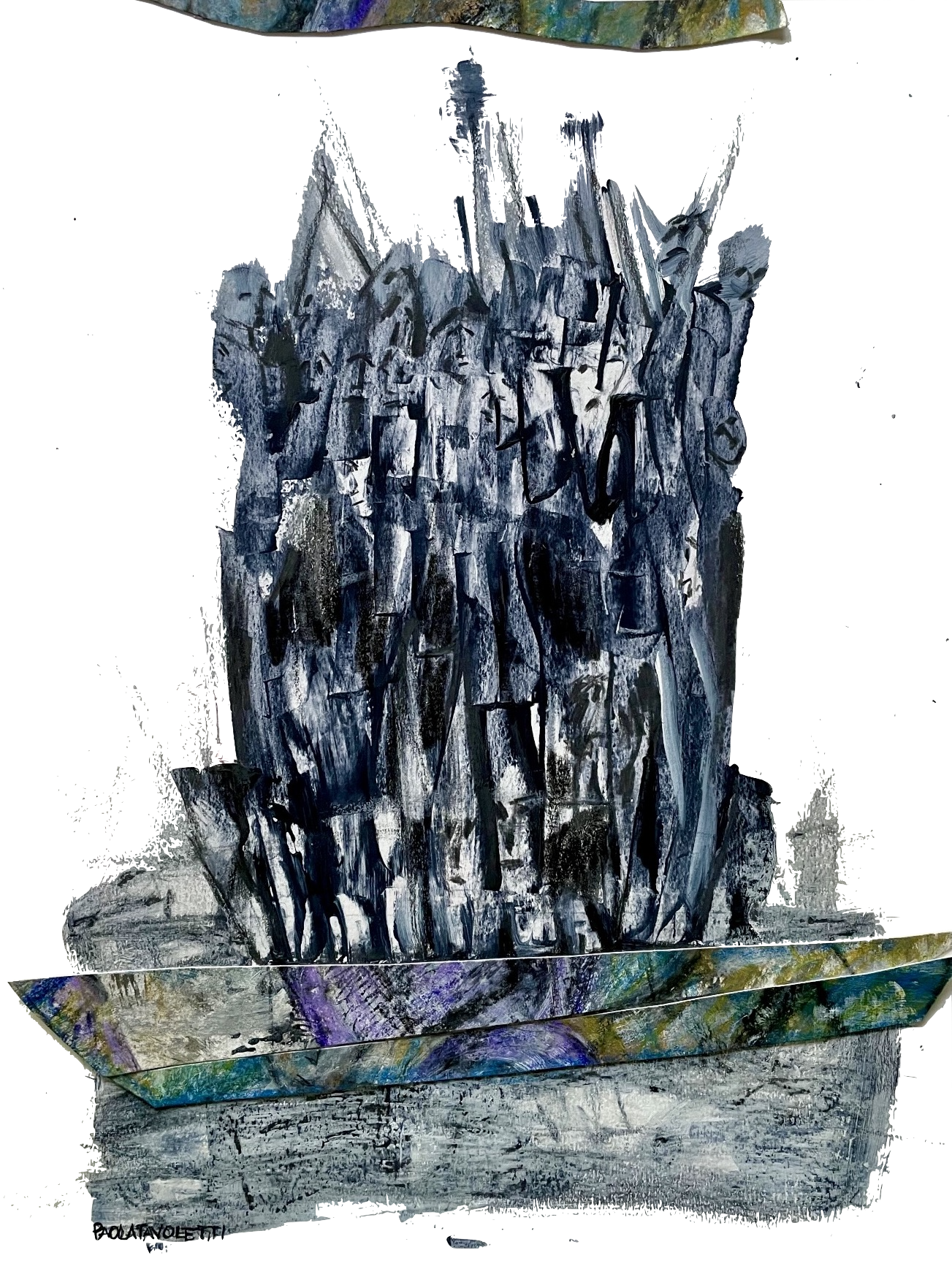

Maybe seeing the dead had nothing to do with the dead at all. They were always there, in their own landscape, one that, after some time, I could access while existing in our everyday world. I granted myself permission by way of acceptance, by never questioning when I felt the tingling creep of invisible company up through my spine and a thumping arrythmia that never brought any danger, just animalistic awareness of surrounding life. I could be on two simultaneous planes at once. I called the one with the dead “the land of the invisible,” and for the first few years of my young life, it was the world that guided me more than here, more than now, more than the physical landscape that we all know exists because we walk upon its surface. But I never wandered too far there. Somehow, it felt disrespectful, like because I was still technically alive in body I didn’t fully belong. At times, though, spurred by insatiable curiosity and a dreamer’s brain, I’d lose myself entirely, maybe for minutes, maybe for hours. Now, I’m not sure if the loss of time, or its absence altogether, was a side effect of some magnificent astral travel ability I was dumb to as a girl, perfectly naïve in a gift that was simply enjoyed, or if it was part of the gift of being young. But if I wandered too far into either world, I could always find my way back to the middle. It was like my grandparent’s living room, those beams. Everything was connected by big and sometimes complicated, tangled lines. All I had to do was pick one and follow it home.

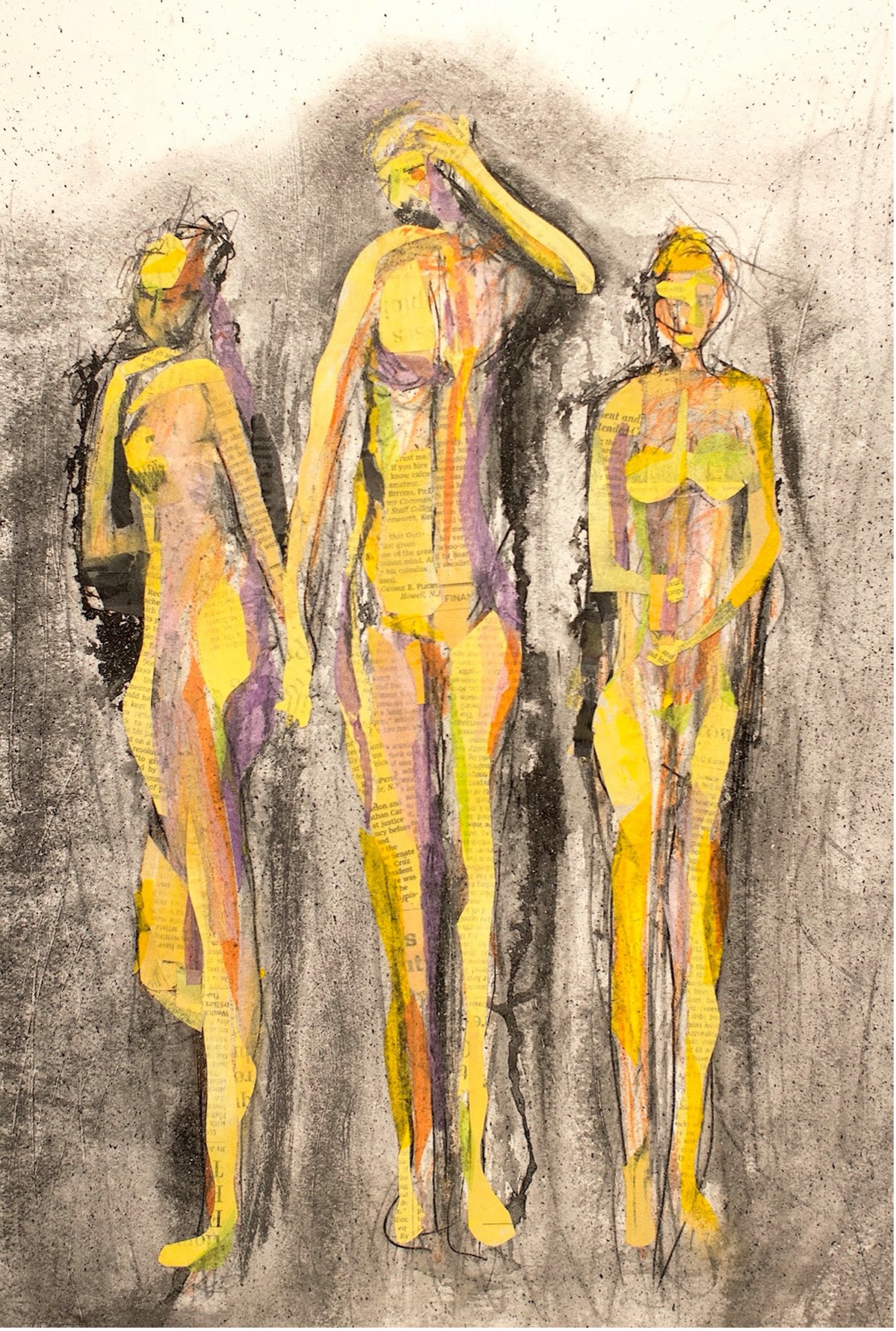

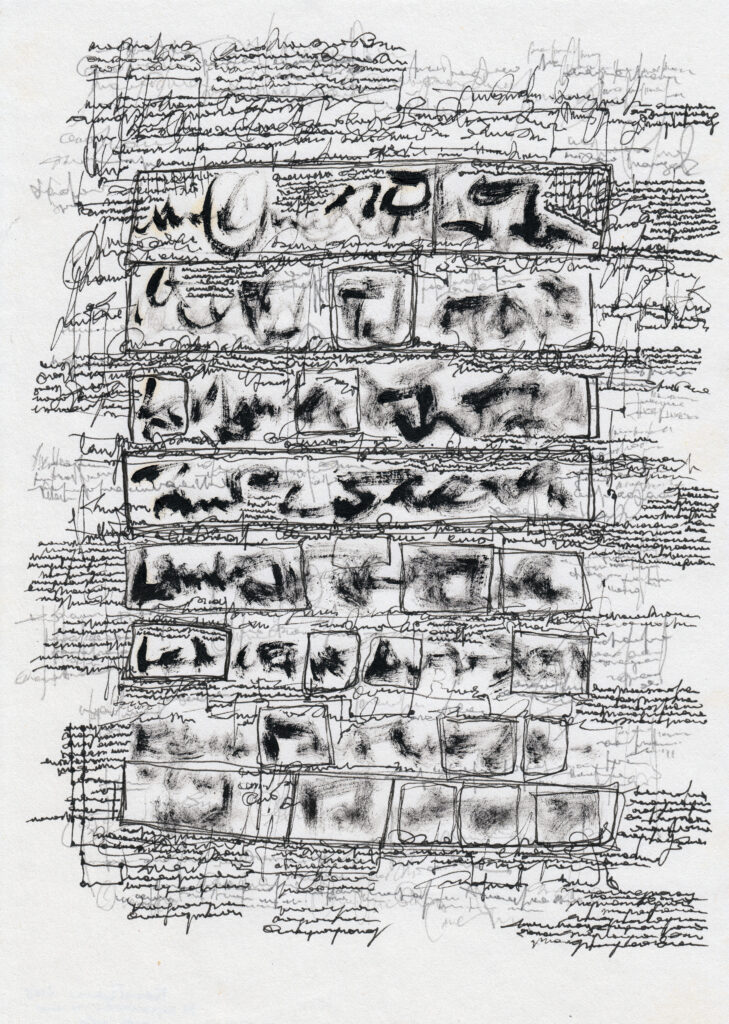

It might be impossible to paint the land of the invisible as a landscape. I wonder if my Pépé could. It’s a world that we all feel, that we all know is there behind an invisible curtain and it drives us forward, gives us gut feelings, synchronicities, coincidences, and if we’re lucky, sounds, like waking up to piano music in the night only to see that no one is sitting at the piano but knowing it’s my Grandmother playing from one of her music books I have now, sounds like this that ping in our hearts as if we all suffer from that arrythmia that tenderly and seriously reminds us we are not alone. It’s the moments that sometimes last only seconds where we know that we are part of something much, much grander than we can possibly understand the way we do algebra, or rules, but we feel its brief bursts change us from the inside out, like what it would be to gulp down a bolt of lightning. If my Pépé ever felt this while he was alive, maybe he could paint an impression. Maybe that’s what he was working on all those nights out on the porch in the dark while I watched him propped up on my elbow, lounged on my floor mattress, waiting for him to acknowledge me acknowledging him before he vanished like pulled apart gossamer. I loved wondering what he was painting. I loved even more imagining it was a picture of our shared invisible world, my Mémé looking over his shoulder suggesting more light and less shadow, pointing to the darkest corners.

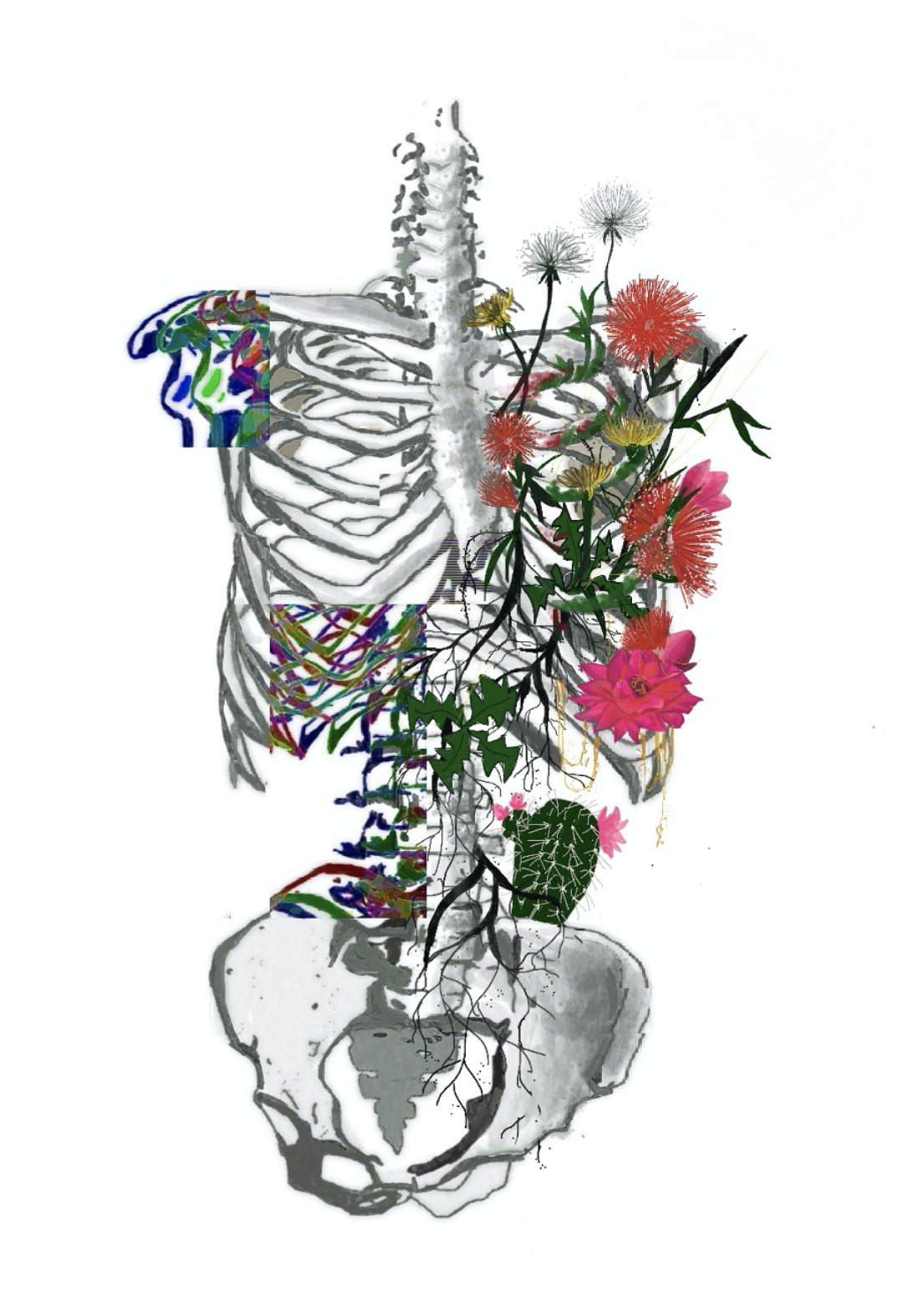

I wouldn’t know where to begin painting the land of the invisible. The best I can do is put words to it so a picture forms somewhere in your ether space right between your eyes and behind your forehead. I describe it this way – once, on a hike, I wandered upon the skull of a doe in the woods. It hung on a tree like a primitive ornament, a gnarled branch poking through one of her eye sockets. Enamored by its elegant fragility and gruesome lines, I took it home. I had to have it. I cleaned it in hot water, peroxide, dish soap, and bleach, scrubbed it gently with a toothbrush, polishing each individual tooth which felt human, like brushing my own, and in the stark image of death that was the skull, I felt only life in my hands. Her bones supported life. I knew her gentleness and grace, physically touched by her sweetness like slight electric currents coming through me, and when I let it happen, I felt her power, too, to leap tens of feet at once, to birth fawns in late May and protect them and carry stories, folklore, and secrets of the earth. Her bones once gave a shape to her invisible force, and through this shape in my hands, through brushing her teeth, I understood that our landscape, the one here and now, is the invisible taking shape. We are all the shape of something that cannot be seen. It’s expressed through our flesh and bones, our hair and smiles and cries. I suppose then we are all landscape paintings, capable of weathering and change, capable of push-pull, of gravity, of regeneration even after we’ve been hurt, and giving sustenance to whoever is hungry and haunted, too.

Even though this was the most gorgeous discovery I knew then, it wasn’t exactly easy to explain. I knew I had to think of different ways to explain this invisible world. I was constantly seeking ways to express it. But nothing ever felt right. This world had an essence I couldn’t capture in words, pictures, comparisons, or any kind of art. I couldn’t give shape to it the way it gave shape to me, but in order for it to exist in the “real” world, I had to give it a shape. How would I make the invisible tangible so others could understand it better? It was ethereal. Telling people I could see the dead was like something straight out of a horror movie. I was ready for jokes. Mostly, I knew it was inconvenient for those who lived in a certain kind of mental comfort, the kind where “impossible” was an immediate label for anything unknown. It was scary. That’s what people really meant. That’s what no one, mostly adults, cared to admit. Instead, saying no or telling me it’s not real was the solution to maintaining boring adult status and to re-epoxying the fixed belief that anything unknown was impossible. People only label things that add value to their existing power in life. Like the way they admire dead butterflies framed in glass or pressed flowers in heavy book pages. Delicate, pretty things with names were okay to capture and know. But I saw through this. I still do. I see my dead family. I see dead strangers, too, and dead stories play out on repeat like silent sepia movie reels, the same figures in the same clothes with the same expressions walking through the same walls and up the same stairs. I see through convenience like its one of my ghosts. I see that impossible is easy. Possible is much harder.

In first grade, I told my mom my secret. I had to. My first-grade teacher, Mrs. Byron, called her one afternoon when I insisted over and over again that I could see my dead Uncle Steve, just his bust, floating outside her window. My planes were crossing frequently at school, my landscapes overlapping, and it was difficult to keep it to myself. It was distracting. Despite my pleading, Mrs. Byron never turned her head to look where I pointed. He was standing right behind her. When she told me it wasn’t real, I only said one thing – you didn’t even look.

She told me it was impossible.

There it was again, that terrible word.

Mrs. Byron was frustrated. This wasn’t the first time that my crossing of planes into the land of the invisible in class was disruptive. When a classmate of mine, Ivana, asked why I was so quiet during indoor recess one afternoon, I told her it was because I was talking to my Uncle Steve in my head. That’s the way it happened usually. I knew his words in my head but because I felt them first in my chest. He was a ghost, I told her, so she wouldn’t be able to see him. Ivana didn’t say anything to me. Later, I learned that when she got up to go to the bathroom, she told Mrs. Byron I was scaring her by talking about ghosts. Mrs. Byron told me to leave that part of my imagination at home. I told her I couldn’t, but failed to say why.

I cried, not because I was technically in trouble, but because whether you are six or sixty, someone telling you that your world is impossible feels awful, like reaching into a pocket for a key that’s not there. It made me feel immaterial as a girl, as person, as the brave navigator of the invisible world, the world that gave me shape an imbedded in my bones a map of lines to follow that would give me choice and adventure and tribulations and victories. But right then, being told it wasn’t real, I disappeared in front of Mrs. Byron like gossamer in the dark. And what’s worse is because I cried, and because of my insistence of what I knew to be real, she called my mom. It was the convenient thing to do for something so inconvenient in her day. All labels do is limit us. And, when we don’t fit into any existing ones, we disappear.

My mom came to school to pick me up that afternoon, and rather than waiting outside the school in her car, she was instructed to come inside so that Mrs. Byron could speak with her. Earlier that afternoon when Mrs. Byron had pulled me out in the hallway to calm me down and tell me that my mind was playing tricks on me, that my world, the one I felt as profoundly as I did love and fear and hope, wasn’t real, she explained to me that my mom would be coming in today as a treat. I might have been six. But I knew words and sweet talking when I heard it. It wasn’t a treat. It needed an “h.” It was a threat. Calling my mom implied that I wasn’t to bring this up again. It was too inconvenient. I worried what place there was for me in the “real” world if all of me didn’t fit.

What I understand now from this treat-threat-tactic is that not only was I inconvenient, but she was scared. She never turned her head to look at where I was pointing behind her at Uncle Steve. She refused to listen to my description of him. What would’ve been so bad if she saw what I saw? For me, it would’ve been nice to have company, a co-traveler through the world of the invisible. We could’ve painted our impressions of the landscape and compared them. I didn’t have anyone to do this with and I wouldn’t for most of my life. I didn’t know that then. Despite the constant, invisible company, I was and would be a lonely traveler across my landscape, but there was an equipoise about living between two worlds. I was always reminded of how to live full and well among the corporeal because I saw the dead. People always say that life is short. People always talk about the best way to live. People sometimes talk so much that they don’t do any of it. The answer, to me, was obvious. Don’t be so dead all the time even when you’re living. Even the dead weren’t so dead. They seemed to be having a good time.

When my mom came in and talked with Mrs. Byron, I sat at my desk and pretended to write in my journal. They stood about a foot apart, face to face, and Mrs. Byron told my mom that I got upset about my Uncle Steve today, just like that, plain and simple, no story about me seeing his floating transparent bust out the window. She said I was upset about my long dead Uncle that I never met.

My mom crossed her arms.

“Uncle Steve?” she asked. “My brother?”

“She said her Uncle Steve. Apparently she never got to meet him and she was very upset about that.”

“Yeah, that would be my older brother,” my mom confirmed.

“She just burst into tears, said she never got to meet him,” Mrs. Byron threw her hands up in the air with open palms toward the ceiling on the word burst. Her body language implied that what happened was dramatic nonsense, and her tone was a poorly acted surprise. I was still sitting at my desk folding the edges of my journal, fidgeting with anything I could mold in my fingertips. She was talking to my mom as if I was invisible. For once, I was a ghost. I panicked, like feeling for the key in an empty pocket again. Who would see me?

“That’s unusual. She never really gets upset that way,” my mom glanced over at me. She winked at me, just like Pépé did right before he disappeared. I wanted to jump up and tell her how much I loved her for winking, how much I loved her for saying it was unusual in the perfect tone, kind, gently accusatory and confident that she knew much more than Mrs. Byron and knew it was much more than being upset over someone dead I never met, but now wasn’t the time. More importantly, I sensed that my mom sensed my discomfort. My mom couldn’t see the dead, but she was intuitive, the best navigational system for the world of the invisible. Sometimes she knew when something was bothering me before I did. If anyone was to understand the land of the invisible, it would be my mom. I decided I’d tell her my secret for several reasons. First, I didn’t want the reputation of a cry-baby, I wasn’t one and I wanted it to stay that way. Second, I wanted to correct Mrs. Byron’s lie. Lastly, it felt like a good opportunity to let someone into my world. There was a chance my mom could navigate it better than I thought.

On the way home in the car, I told her what really happened. I told her that I saw her brother, that I see her brother often in my classroom at school. She was confused as to how I would know it was him. I never met him, never saw a picture of him, and she didn’t talk about him. I told her it just happens in my brain, like a fact, the way you look out the window and know the color of the trees, grass, and sky. It’s just there. The first dozen times it’s miraculous. Then, you get used to it, like everything else that surrounds you in a new place.

My mom said the best thing she could’ve ever said after I told her all of this.

“Oh, okay,” she said.

She didn’t tell me it wasn’t real. She only told me she was happy that I told her the truth. There was a lot to tell her. I told her later that night, sitting at the foot of her bed while she folded laundry with the Dick Van Dyke show softly playing in the background, about the land of the invisible. I told her how I saw Pépé and Mémé, how in the middle of the night, sometimes I’d hear loud footsteps on the stairs and whenever I’d get up to see who it was, they’d run away, like they were playing and didn’t want to get caught, and, I told her that sometimes, I know people’s secrets just by looking at them. I can feel them. They vibrate. I know feelings and hopes and wishes and fears. They vibrate, too. I can see them.

“Doesn’t that scare you?” she asked me. She still asks me that.

“Sometimes,” I told her. “But not normally. It’s the way it’s always been.”

This was true. It’s no different than the way we all grow up in our homes, towns, cities, and around people, giving into and resisting the way the world shapes us. I know now that my invisible landscape has shaped me into a fear-chaser, someone who challenges boundaries, somehow who revels in solitude and quiet and books and movies, all landscapes I love losing time in, but will speak up to teach and to love and to guide when I’m able. I have spent my entire life balancing on the line that separates the invisible and the tangible, like standing before tall grasses where something familiar and unseen ticks with life but never shows itself, assigning meaning where I feel it, even if I can’t quite say what is. I’ve chosen to be this way. Ironically, it’s seeing the dead that gives my life its shape. Embracing the uncanny, even in the darkest of times, has unfailingly led me to where the light is. Best of all, it’s allowed me to see the light in others, too, to know their valleys and fields and rough terrain where its hard to stay sure footed but they could maybe do it if given a hand.

About a year ago today, I was visiting my mom, sitting at the dining room table when she opened the closet under the staircase while cleaning, reached in, and pulled out two canvases. She handed me one of them. It was a landscape painting of a farm in Vermont. There was a barn, rolling hills, a rickety fence and blue skies. In the corner, the name Rudolph was painted in brown. It was where Pépé grew up.

“Oh, I forgot to show you. Look what I found,” she said.

I held my Pépé’s landscape in my hands, knowing he’d sat there on a stool just like I’d see him do in the night, painting a landscape of a world that had molded him, the dirt roads he walked, the red barn that must’ve screamed red in the direct noon sun based on how very red he’d painted it and where the sun shone in the sky. I held his world while fully immersed in my own, feeling him in this painting the way I felt the doe in her bones, the way we all feel someone’s stories stowed inside their cells when we meet them, the way we all know that we, as humans, carry landscapes with us as ghosts already haunting this world. The part where we get stuck is not having the language to explain or accept that it’s our intuition, the invisible and greatest navigator of all, that moves us through.

On the other canvas, the same landscape is covered in snow. I held this version of his world in my hands and was reminded how capable of change we are, how quickly we can go from being blanketed with snow to a screaming red warm day. Mostly, I felt the sharpness of this change, the suddenness of the process and understood the inherent pain of transformation. Still, I wonder that if we knew being dead wasn’t really dead at all, that gliding through the dark into what seems like nothing was actually something, just following a ceiling beam back home to the sewing room or holding a painting in your hands, what would we call it then if we were to love death into convenience.

Allie Dixon’s essays, fiction, and poetry are published in Writers Digest, The Threepenny Review, SLAB Literary, PRISM International, Ruminate, Causeway Lit, You Might Need to Hear This, Sad Girls Club, Button Eyed Review, Southshore Magazine, and Beyond Words Literary Magazine. Currently, she’s working on finishing her debut novel.