A Friend

by Atlas North

He is a weight for others to carry. His mother will carry him to the hospital and back home several times during his childhood before their relationship frays into thin conversation and then nothing at all to pass between them. His siblings will not bear him but for a nagging burden at their ankles which they ignore and shuffle along still; they consider him inconsequential to their ambitions. His wife, should he be fortunate enough to be marriageable, will carry him like his mother for a time until she’s sick and crawling to her deathbed whilst whispering her every regret: his name so frequently upon her lips then. And while this weight has been bothersome to others it is no more troubling to them than for himself, who bears this worst of all. The aches in his back an unending agony and the lead in his limbs that he cannot lift them, cannot hope to move from his wheelchair, only able to lean back and observe and take in the world that has slowly abandoned him to his own dysfunctional devices.

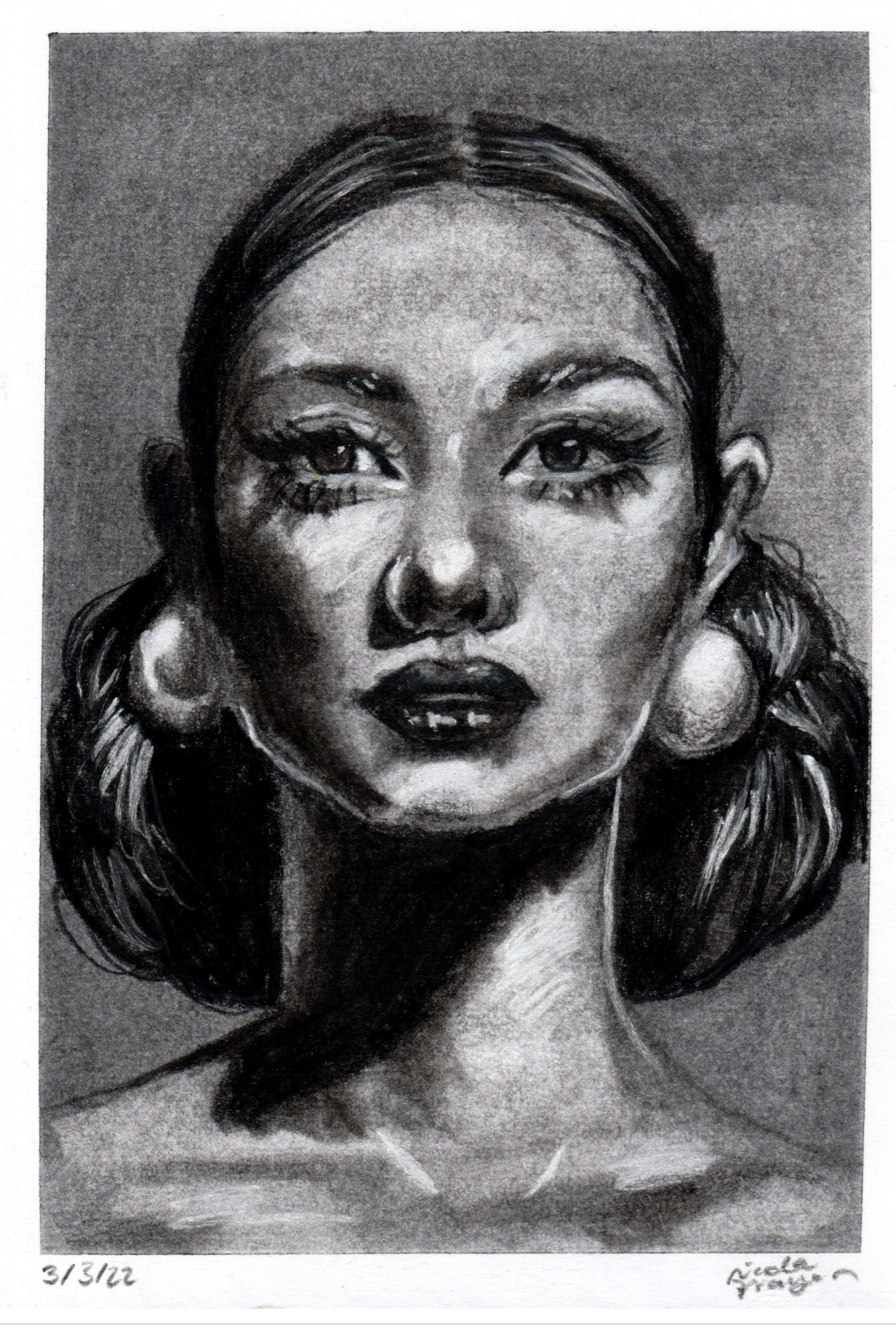

In his single-level home he has parked in front of the window in the foyer, watching birds flutter and flit about the untrimmed bushes that line the metal fence which borders his modest estate. As these birds play in the air, he wonders at the freedom granted to them by their very nature, taking flight whenever their fancy suits them. What would it be like to flee into the pale blue sky and become nothing more than a figment to the naked eye? The birds furious and flapping swim away and his gaze following their trajectory becomes distracted by a familiar face in his periphery. Tan and incandescent in a manner that only she can achieve, with soft brown eyes and a smile to reach them, adding further light and depth to their color. Or perhaps that is the sun, angled in such a way her irises shine a golden amber. Her smile is for him and so is her wave, as she opens the gate and saunters down the promenade toward the front door. He turns his chair, slow-going with the strain of the electric motor, and greets her as she walks in.

“Hey, Paul. How’s it going today?” Her voice rings high, less true, that attempt at feigned optimism too discernible. Even she has to roll her eyes at her subpar theatrics.

“It’s alright,” he says, the act of speaking an arduous but worthy endeavor, especially for the sake of engaging her in conversation. To hear her speak, if only to liven up the monotony of societal bustle outside, and to practice new forms of speech techniques that would allow him better control regarding his enunciation. After all, what company he keeps is that which he makes for himself, by invitation or by retreating into his own thoughts. But every other day, his mood is brightened, his efforts redoubled, for she is the anomaly in his otherwise rote routine of waking and eating and existing. The latter of which his desire to do so had dwindled before her arrival, for what was the point? Being, without the meaning which gives it life. That which he lacked, that purpose, instilled itself within him the day she was hired. To be there for her as others would not, or could not be. He harbors no delusions about their relationship: she is his caretaker, and he is her patient, and whatever else between these titles is but a byproduct of spending so much time together, orbiting each other’s lives. This is a fact he appreciates, despite his burgeoning romantic affection; that though he grows ever fonder of her, their positions are static and thus she remains a part of his life so long as she remains his employee. Longing at times a lingering malcontent he must dismiss.

“Did you want to go around the block a few times today?” she asks as she grabs a glass from the kitchen and fills it with water, then retrieves his pills, the muscle relaxants, and brings this all to him. He grins at her blunder.

“Dammit, sorry, Paul.” She helps him hold the glass to his lips as he sips and swallows two pills.

“No worries, Lina. And for sure, we can go around the block a few times. Actually, can we go a bit further today?”

She stops, seeming to think on this and asks, “Will you have the energy?”

“I don’t see why not.”

“As long as you’re sure.”

She asks him if he needs a bathroom break and he denies her offer, partly for the embarrassment he feels that another human being must assist him in what he considers a crude and demeaning occupation regardless of its unfortunate necessity; partly because he wanted to delay that inevitability, for the sake of whatever dignity they could scrounge. She goes through the house and cleans: the floors, the windows, the counters and desks all dusted; the pantry organized after a weekly trip to the grocery store; medication carefully arranged and then dispensed; laundry done throughout the day, during which she attends to his every beck and call. Should he need food she would prepare it to his exacting specifications, though he is hardly ever so fastidious.

The morning almost spent as the sun brightens and moves along its hourly arc, they watch a Japanese animation together while munching on some nuts and berries. Not his preferred snack but a meaningful compromise to her insistence that he maintain a salubrious diet. She asks him a question regarding the show. He answers, keeping her informed of character names and important places and the current plot arc. Eventually, he putters. A silent beat before, “Do you mind if we don’t talk for a bit? I don’t mean to be an asshole, but I’m running on fumes.”

She smiles, somehow still chewing. “For sure. Are you still gonna be up for a jaunt later?”

“A jaunt?”

“You know what I mean.”

“Yeah. Yeah, I will. Thanks for understanding.”

“No problem.”

His respite does not last long as his curiosity takes hold, and after another pair of episodes he asks her what work she was looking for before coming into his employ. She seems at first to ignore the question entirely, upholding the false pretense of being captivated by the show, but there is a drooped draw to her lips, and when she responds finally her voice has shrunk, that of a feeble self kept to our fetal origins.

“I was looking for a publishing gig initially. Uh, actually, I just wanted to be an agent, represent talent, mediate contracts, that sort of thing. But, well, to be honest, this place is in the middle of fucking nowhere and the publishing market exists as this ephemeral entity kept alive only by indie bookshops and the occasional Barnes & Noble. I was pretty put out. Regretful, that I had packed up my life and moved halfway across the country for a dream I wasn’t sure I wanted, but would certainly make my parents proud. And then I found your ad online, you know, and the rest is history.”

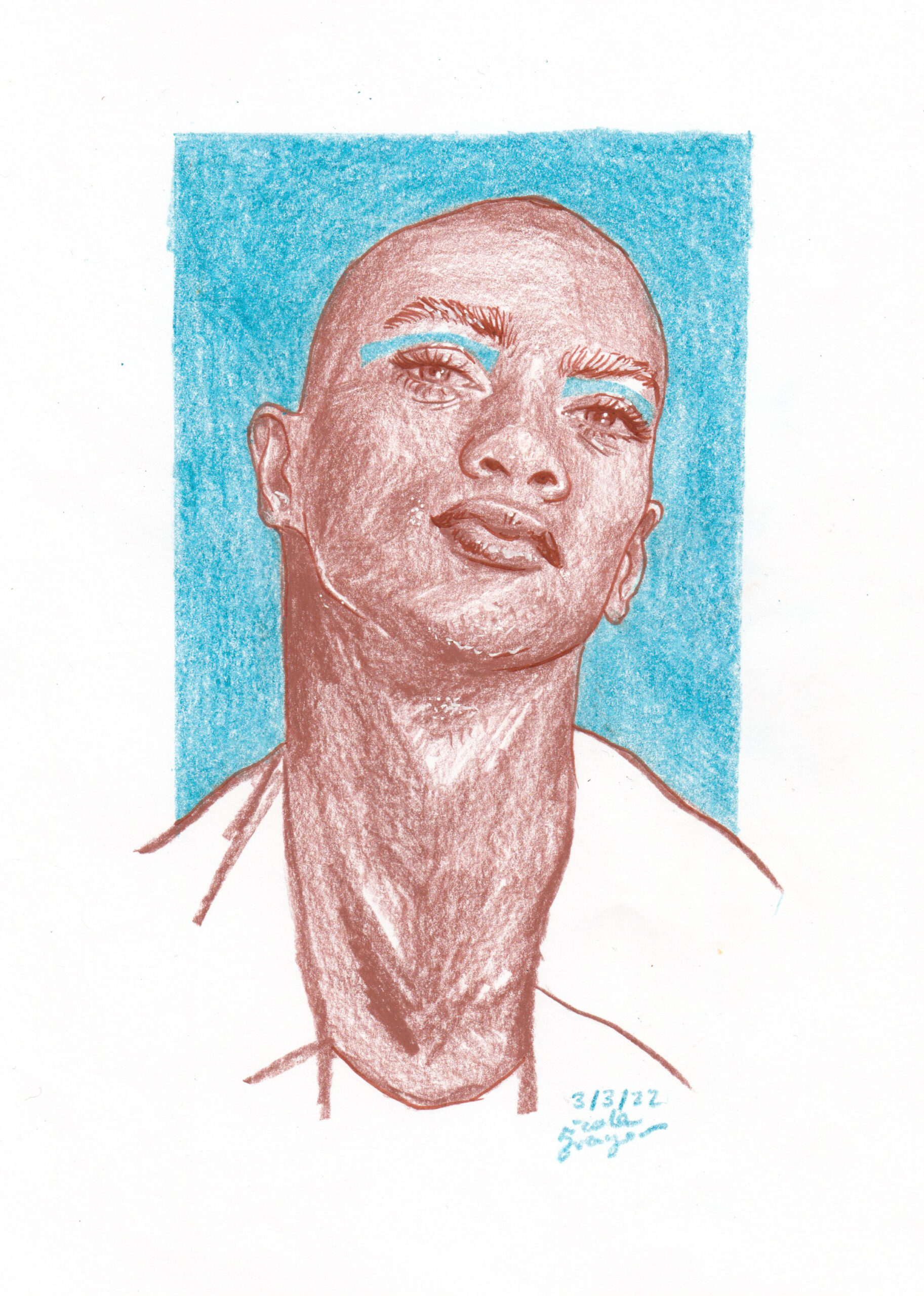

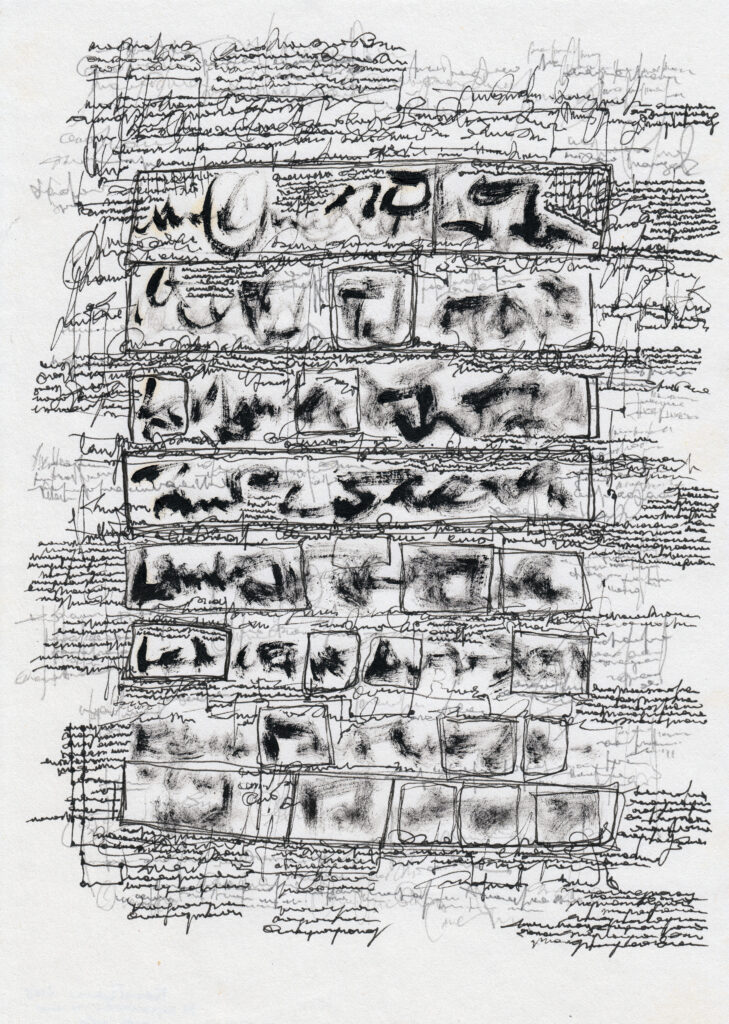

He gives her an affirmative gesture, a slight if imperceptible nod and an attempt to raise his left thumb, but does not speak, still without the stamina to do so beyond a few phrases at a time. They fall asleep, first he then her, and the house collectively settles. The TV is off and the chores are done thus the quiet here is earned; their rest a much-needed reward. When he wakes next he spots her sketching, or so it seems by the movement of her pencil upon the paper, fluid motions far too elaborate for mere script like the weaving of a tapestry only she can design. So in tune is she to this process that she does not see him move, nor does she hear the whine of his chair as he inches closer to snoop on her work, to peek behind the curtain before he can be admonished for any impropriety.

The drawing consists of a landscape, grasslands ruffled by the gentle fingers of a modest wind, but here captured as a still-frame, in the midst of that upheaval. Two figures depicted from the back, looking outward and away. In the distance are mountains, though not as they are usually drawn with jagged edges and violet-blue shading, but as a wall or a fence-line opening up just to swallow whole. The figures gaze on, unfazed or awed their body language does not say. There is a sense of fantastical scale in tandem with photorealistic exceptionalism which causes Paul to gasp, and for her to suss out his spying, to clutch her sketchbook to her chest.

“Hey, didn’t know you were awake, um, I was just, well, it’s just something I’ve been working on for a while.”

“It’s great. Sorry if I scared you. I was just curious.”

“No, it’s alright. I don’t normally share my work, though, so, um…” She puts the sketchbook down and stretches, arms high, legs out. “Do you need anything at all?”

“I’m a bit famished but I’m more concerned with why I didn’t know you were such a damn good artist.”

She stands and heads to the kitchen with him in tow. “It’s something I’ve kept mostly to myself as my own thing. No one else really knows about it.”

“No one? Not your parents, or… your pet parrot?”

“I don’t have a parrot.”

“I ran out of potential confidants and decided to go with common household pets.”

She turns, stupefied. “And you didn’t think of, say, a dog? Or a cat?”

“I was under a lot of pressure. This is beside the point, which is that you’re a damn good artist and you shouldn’t be here hand-holding an invalid. It’s a waste.”

“That’s pretty harsh. It’s not hand-holding, you’re not an invalid, and it sure as hell isn’t a waste to work for a living.”

“It’s glorified babysitting. I’m pretty sure I meet the definition of ‘invalid’. And your work while laborious and undignified is not a living upon which one should make. You deserve better than wiping my ass.”

“What the hell is with you?”

He says nothing, for the things he has said are truths which his heart cannot reconcile and none could ameliorate much like a bullet in the gut its molten metal burning the life within. She pauses in her work and approaches him like a tentative stranger seeking for a means to help.

“You yourself have said that you want people to see you as more than what you seem, yet this is how you behave? Is there something else going on?”

“I can, um, I can feel it, you know.”

“Feel what?” She kneels before him and rests her palms on his knees.

“How much I weigh on people. Eventually it becomes too much.”

He turns not waiting or not willing to wait for a reply and goes to his bedroom and by the press of an interior button the door shuts. Not a slam but a gentle closing that is somehow too violent for this sequence and abhorrent to the woman standing in the kitchen. The injurious disappointment of a genteel relative unable to righteously express their anger and thus cannot do so in any context save for a rage borne from death. This quietus place a graveyard’s demeanor.

She goes to the door and knocks upon it. No answer. She calls his name, soft in its sweetness and sweeter for the voice that shapes it. Says she’ll be waiting for him, whenever he’s ready.

***

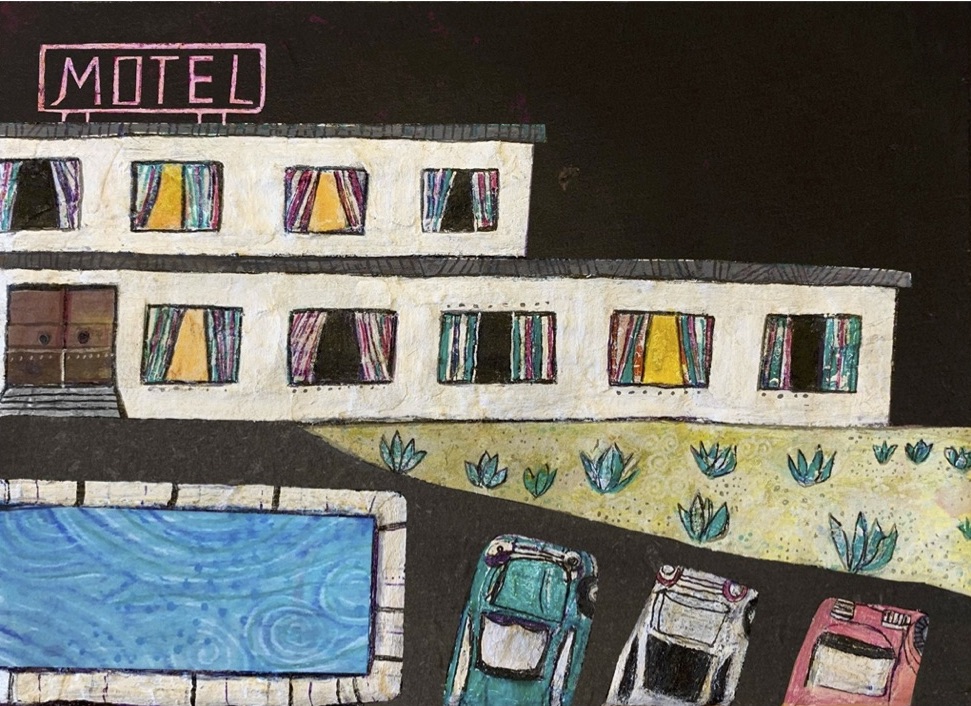

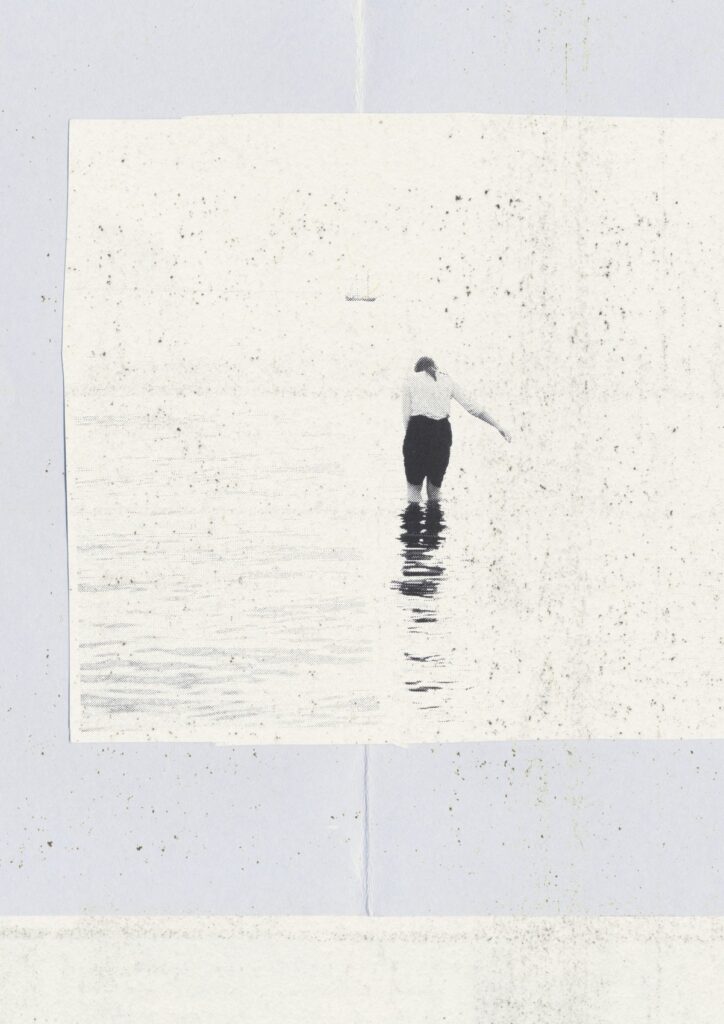

It is later when they take their agreed-upon outing, when she opens the front door at his request and beckons in the day. Spring as a season for him maintains a most enjoyable equilibrium: warm, but not exceedingly hot, with a gentle breeze to break the continuous heat. Their pace is dictated by the terminal velocity of his chair, little more than a power walk. Cracks in the sidewalk lurch and drop his wheels; the percussion to his life’s refrain. She stays at his side her hands in her pockets or tied behind her back and her eyes downcast or cast about. Stillness antithetical to her nature and he smirks at the idea. She, noticing this, mirrors his smile but completes it with a luminous grin as bright as the noon.

“What are you smiling about?” she asks.

“Oh, well. You have a bad time trying to stay calm.”

“Do I?”

“Well, maybe calm isn’t the right word. Focused?”

“Yeah, I’ve got a thing about restlessness. I like being on the move. Makes me feel like I’m doing something.”

“In general… or…?”

“Mhm. I’m a shark in that way.”

“A shark? Hmm. I’m a starfish.”

“A starfish?”

“They stick to one place fairly well.”

“Huh. What about land creatures?”

“A sloth.”

She goes to laugh but tries to snuff it with a hand to her mouth. “Oh god, I’m so sorry.”

“It’s fine, Lina. It was a joke. You’re supposed to laugh at jokes. What would you be?”

“Oh, I dunno… a, uh, honey badger.”

If he had the faculties to do so he would have nodded approval. Instead he says, “Because honey badgers are highly resistant.”

“Sure. And they’re adorable.”

A decline in the sidewalk belays their talk as he adjusts his speed accordingly and concentrates on trying not to tip his vessel. When that is done and their journey level again, he broaches another subject. “Where do you see yourself in five years?”

She chuckles. “Talkative today.”

“I need the practice. And I’m bored. I must need entertainment.”

“You find my future entertaining?”

“I find the prospect of people having aspirations admirable.”

As he goes onward she slows and eventually halts and it is a few long seconds before he realizes and turns around. Face-to-face he asks, “You alright?”

“Do you not think about your future, Paul?”

“I… Well… I don’t think there’s much of a future for me.”

She hesitates. He motors to her side and looks up at her. Within him some arcane vitality gathers enough strength for him to lift his hand, then for that hand to reach out and place but a single finger on her arm. She gasps and their stares meet.

“I’m sorry,” he says, that energy diminished, his touch retreating back to his armrest.

“Where do you see yourself in five years?” She severs contact, instead looking away, avoidant.

“I see myself here. Doing the same thing we’re doing now except perhaps with a different aide.”

“You don’t want more for yourself?”

“Is there anything more that I can actually have?”

She nods and hems. “Okay. I get it. Let’s see. I want to be happy.”

“Hmm?” Their excursion continues as it had before, slowly through the neighborhood and around the corner.

“You know, I feel like I’ve worked my whole life for someone else. Um, no offense. Anyway. At first it’s been about my parents and what they think is best for me. They sacrificed a lot by emigrating here. Took a lot of shitty jobs with shitty pay to put me through school and to raise me in the best possible environment. But what they wanted, when it came to my career at least, it wasn’t something I was interested in. Doctor, or lawyer, or corporate executive. They see success as a dollar sign. I see it as being happy. Living life not under the thumb of someone else’s expectations but operating under your own power, on your own time…”

“And what does that look like? Are you talking about your art?”

“I wanna do animation. I want to live in the countryside and live a peaceful life. I want a million dollars and I want none at all and I’m not really sure of anything at the moment.”

“So… animation?”

She nods.

“Why?”

“I think it’s an underrated form of art. And I enjoy it immensely. Avatar: The Last Airbender and Hayao Miyazaki’s films were pretty big for me. What about you?”

“What about me?”

“I know you said you’d see yourself doing all this again in five years but is that what you really want?”

“That doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter if I wanted to be a pilot or a basketball player or a crab fisherman or a sheepherder or a textile farmer. My body is a casing for my consciousness. A puppet without strings. I’ve accepted it. It’s okay. But now I need you to accept it. I need you to really understand it.”

A lull expands within the conversation, shaken by revelation. Like the murmur of sleeping giants whose wakefulness could dismay the world. Restarting their engagement comes with great difficulty as an awkward aura rebounds one from the other, and despite their physical closeness they drift ever so distant. By careful observation he notes how her body has turned opposite him as if raising a shield. How she cannot seem to look at him, not even a glance, and how her shoulders sag and her posture slouches and her knees bend sluggish the tableau of a trudging refugee. She carries an invisible weight he instantly recognizes, from his mother, and his siblings, and his former spouse.

He tries not to notice but memory and reality often feel like kin, de ja vu, c’est la vie. A wife walking ahead, onto greener pastures. A mother despondent at his side. No answers to his inquiries nor reaction to his jests. Just a placid reflection of her indifference. A brother and sister, where are they? Prescient prophets that fulfill themselves. What is Lina now but another that could not bear him?

“You’re a good friend, Paul. I’m grateful,” she says, so soft that he almost mishears.

This is when she looks at him, eyes a blissful red blessing quiet tears. Not the milieu of exasperation but of hard-won jubilation, accentuated by a small smile. She steps close and kneels before him, hands on his own.

“You are my best and brightest friend. And I love you.”

At these words he feels within a tectonic shift and he smiles as Atlas may if he but shrugged off the World. When after his quest is done he can breathe a long-held breath and weep relieved unto the dying of the light.

Cody De Palma is a recent graduate of Southern New Hampshire University and has his sights set on an MFA program. He lives in Nebraska with his wife and three pets.