Sometime You Have a Toy Gun

Brandon Diaz

Sometimes you have a toy gun. Sometimes you have a toy gun that is blue, shaped like a machine gun from a Chuck Norris movie, with an extended clip, although you do not know what an extended clip actually does. It looks cooler. Sometimes you have a blue toy guy with an orange tip, just in case anyone might confuse it for the real thing. Sometimes you have a blue toy gun with an orange tip, whose trigger hinges back slowly when pressed, producing a mechanical sound that mimics the firing of a fully automatic weapon like in a Richard Bronson movie, but only slightly, lest it be confused for the real thing.

Sometimes you run around Grandma’s house with the blue toy gun on missions for imaginary bad guys. They look like big throw pillows, or cushions from chaise lounges. Sometimes the bad guys will be shooting at you as you round the corner down the long hall toward Grandma’s room, where you race over the plastic runner, dodging their bullets, almost convincing yourself of the real danger, and like a hero, hurtling through the air, landing on the crisply made bed (the way only Grandma makes), falling to the far side, where you dismount from a roll, in the safety of the bed’s cover. Sometimes that corner of the bed is your car to hide behind, or your stacks of warehouse crates—the ones where the drugs are in the final bust scene.

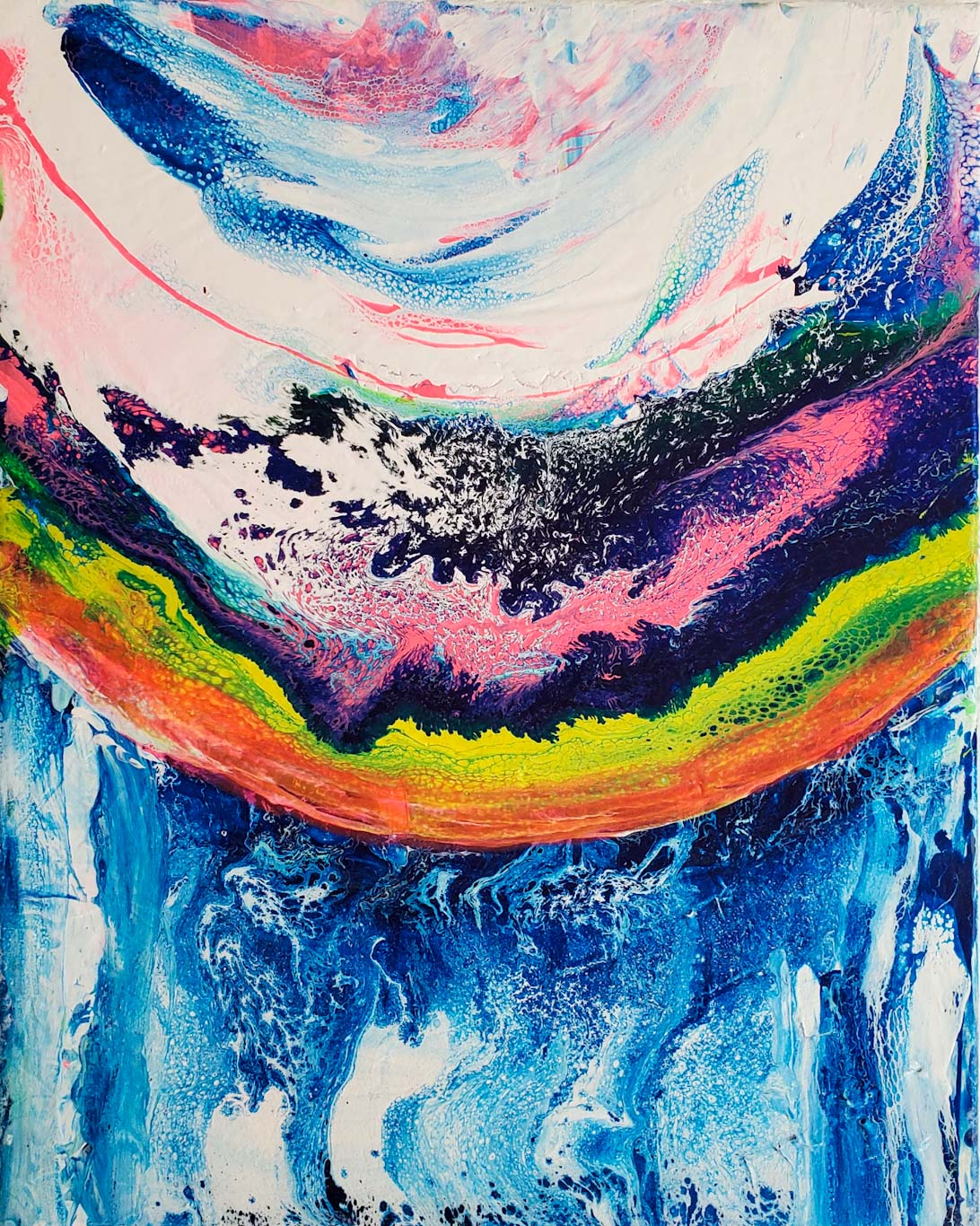

Sometimes Grandma has moved apartments. The hiding place where your blue gun with orange tip has also moved. Sometimes Grandma has rearranged her closet, and only unpacked half of her belongings. The blue gun with the orange tip only belongs to you at Grandma’s house. Guns are not allowed at your house, replica, or otherwise. Sometimes the blue gun can belong to you, but only at Grandma’s, when you’ve found its new location in the mop closet, between two boxes of photo albums. It is on a shelf that wafts of cleaning chemicals. It takes a climb on child’s high chair, kept from the 1960s to reach. Sometimes you try to sneak the blue gun with the orange tip home in your weekend bag, but Grandma will catch you, removing it without remarking on it. It is easy this way. Sometimes you try to sneak the blue gun with the orange tip home after the weekend at Grandma’s is over, and it has slipped her mind to monitor your cunning. But Mom promptly empties the bag of its contents when you get home because Grandma is a smoker. Sometimes Mom says your clothes are drowned in smoke and makes a face when Grandma drives off. Everything must be washed. The blue gun with the orange tip is found and in an exchange you don’t see, is returned to Grandma, where it is once again nestled up between the boxes of photos and a rainbow colored duster. Sometimes you wish the duster had some toy-ish use on account of its magnificent reds, yellows, greens, blues. This coloring is a signifier for toys. Sometimes, when you’re in stores with Grandma feeling that you have behaved, you are likely to hint that you may want one, a colorful figurine with functional joints and a utility belt, but never do you outright ask. Toys cost money. Toys are expensive, and expensive draws exasperation and shooting brows on the looks of not just Grandma, but on your faces aunts and uncles too. Sometimes you merely fantasize about asking for a colorful toy. Sometimes the blue gun with the orange tip is gone. A cousin has been over for a weekend with Grandma. He got to eat junior bacon cheeseburgers and drink root-beer floats. He humped the big brown pillow after propping it up like a bad guy. He stole the gun from its shelf and is creating entirely new action scenarios, full of heroic couch dives, hot lava escapades, bannister slides, while mowing down hostile imaginary ninjas, emerging from piles of laundry to drown his sisters in death as he sprays away with that mechanical rapid-fire mimic. He even does it wearing a headband.

Sometimes when the blue gun is gone, the one with the orange tip, Grandma notices that you are bored. Despite having incurred the expense of cable, which she mentions every Saturday morning as she smokes, and fills envelopes with checks, TV only holds your interest for so long.

Sometimes you must be able to do what the heroes do, after you see them do it. Sometimes Grandma wants to hear your running footsteps running down the long hall, knowing you’re playing make believe. Sometimes, Grandma warms up black coffee in the microwave. She calls it nuking. Grandma listens to see if you’ve found another reason to hurtle through the air, tucking into a roll on her nicely made bed.

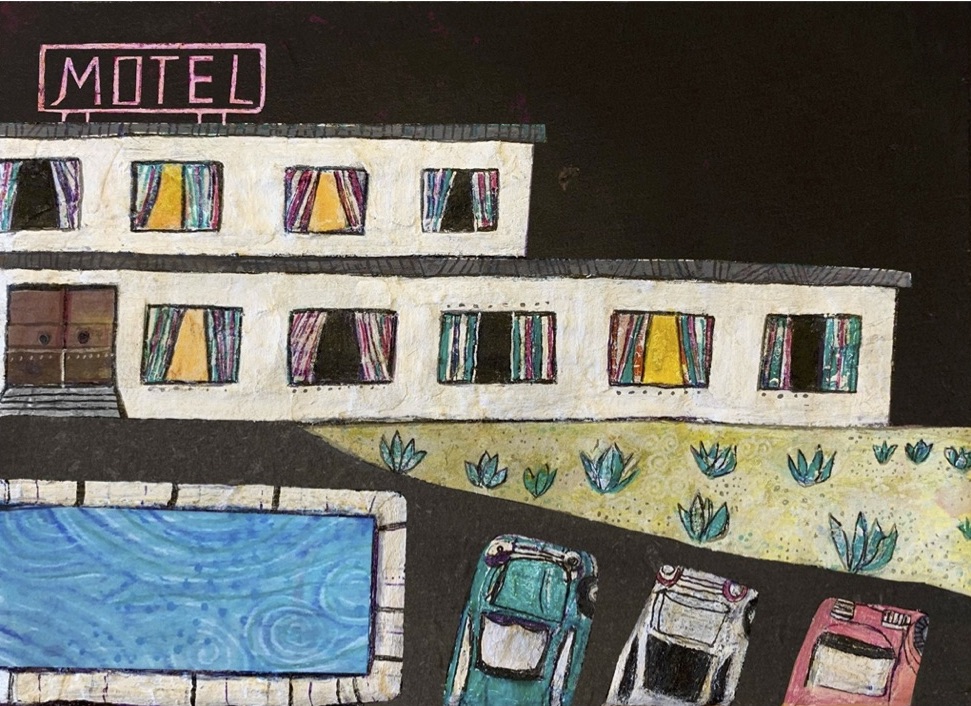

You haven’t. Sometimes Grandma will remind you that you could always ride your bike. You’ve been reduced to Saturday afternoon syndicated movies. They are rarely action films. There are no heroes, or guns, or ninjas, or headbands. One of them though, is about a man who wears a suit and doesn’t like his job. He meets a woman in a leather jacket who catches him off guard with her excitable dress, and deep purple lipstick. They make waves in a bar, and soon the man in the suit casts off his briefcase and mundane life, and they end up at a motel. She uses his shirt and tie to bind him to the motel’s bed. He has never had such an experience before. Sometimes you are searching the TV for more movies like this.

Sometimes it’s been a while since you were at Grandma’s. Sometimes you visited other Grandma with a lush backyard lawn, green like a stadium for the pros. Sometimes at this Grandma’s, your grandfather orders pizza, and lets you help with the design of the treehouse.

Sometimes you miss the other Grandma and your blue gun with the orange tip, but when you go back, it is still missing. You’re up on the high-chair from the 60s. It has been replaced with a plastic revolver like the ones laid out on the blankets at the flea-market. It’s like a sheriff’s in a Western movie. It also has an orange tip, comes with a plastic holster dyed brown like cowboy leather. The gun is not fully-automatic, or even semi-automatic. It makes no sounds when the trigger is squeezed, though the hammer clicks. This is its only satisfying feature. Who are you supposed to kill? Indians? Sometimes you spend entire weekends at Grandma’s ignoring the new gun. Not because of its limited killing capacity, or its cheap silvery paint and orange tip, or its lack of weight. But you are pulled out of the action. Who is the owner of this type of gun? Cowboys? Sometimes you’ve seen them in movies. They look slow and leathery in the face. Everything they do is labored. They are not buff. They do not wear headbands. They are killing Indians and Mexicans and other cowboys, and even at eight-years-old this doesn’t seem right. Mostly though, cowboys cannot dive over crates, cement pillars, Jeeps, speedboats, pallets, big caches of dope, club sound systems, or fish tanks for cover. The best they have are trees, hay, and bar tops, and Grandma’s bed is not an ideal bar top. You do not feel right killing imaginary Indians. However, having a bow and arrow to shoot imaginary cowboys seems better. Indians have face paint, which even if imaginary, is just as cool as a hero headband. Sometimes Grandma allows for projectile toys, until you break something. You never get a bow and arrow, not even the ones with the suction tips.

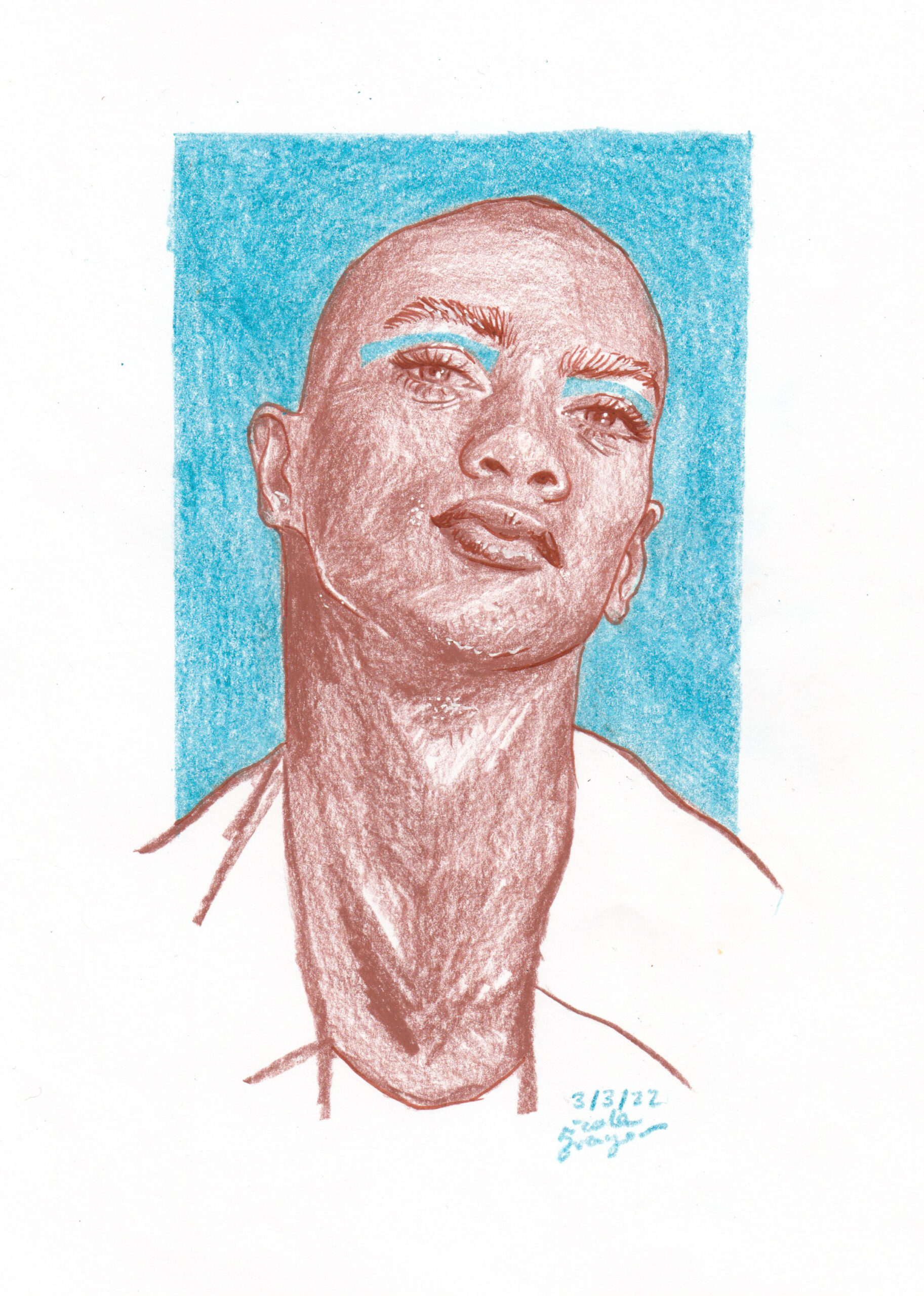

Sometimes Dad comes home from the Army with a Stepmom and two small step-daughters. They are sweet girls and call him Dad. He playfully thumps them on the head as a means of affection. It’s their game. Thumps like compact punches just above the eye. Their father is between jails. Sometimes Dad thumps the step-daughters as they are groggy and bleary-eyed after getting out of the car after a trip to the park. One laughs. The older of the two doesn’t find it funny. He means well. Sometimes Dad seems like the biggest hero on the planet.

He shares his dehydrated field rations from the war, remarking to Grandma about how you love the hot dogs and the look on your face when you discover the powdered ketchup. Powdered eggs are magic. Sometimes Dad is better than all the heroes and all the headbands because he is real. He also has the camouflage pants from the actual army, complete with cargo pockets, for grenades and stuff. He is the real deal. He has a mustache and looks like iterations of three different characters on the G.I. Joe cartoon. You rarely miss an episode. Sometimes you do.

Sometimes, since Dad is home now, he takes to you the movies. Always action. He too, loves the heroes, with their blades, and big titted love-interests, explosions, knives they dip into the bags of dope to test the purity, their haircuts, one-liners, their ability to do the splits between two kitchen counters because the floor has been electrified by two henchmen, their compound fracturing hand techniques, high-kicks, car crashes, exotic locations. Sometimes a hero is in a country in Asia, where the streets are bustling with shorter people hawking livestock. Dad says, ‘I’ve been there.’ This is how you say ‘Thank-You.’ Sometimes Dad is the smartest.

Sometimes Dad leaves his gun on the table when dropping you off at Mom’s. When you go to touch it, Mom cries out, and Dad’s voice grows deep and menacing. Never touch it. It is silvery, like the replacement gun at Grandma’s. But it is no revolver. It is real. It is a real pistol. It looks like one a hero—a cop hero, right on the tail of a bad guy might have at the end of the movie. Sometimes the rap songs talk about Glocks. It might be one of those. It can be held with one hand. Sometimes, when no one is looking you pick it up and it weighs more than all the groceries you help carry in for Grandma. It is real. Hero real.

Sometimes Dad pulls the gun on someone at a wedding. His own sister’s wedding. Your Aunt’s wedding reception, and how about that for omens? It had rained that day. Sometimes the weather is all knowing. Sometimes it’s foreshadowing. Just Dad and you racing to morning haircuts, nearly running reds. Stepmom stressing over getting the girls hair done in time. Their little brown foreheads, shiny with product. Sometimes you are sitting in the car as Dad runs into the store for a few last-minute items. Then you are racing to the church. It is time for your Aunt’s wedding. The truck hits a divot in the road splashing a puddle on a pedestrian in a crosswalk. You both laugh. Sometimes Dad is the oldest child you know. The coolest. Sometimes he’s the safest driver when rushing, but Grandma doesn’t think so. Sometimes, when Grandma is bitching, saying her favorite enjambment—Goddamnsonofabitch—it makes you uneasy. Her stress bites at your legs. Sometimes you say, ‘I cannot stand Grandma.’ Sometimes Dad says, ‘Would you say that if she were gone?’ Sometimes, just sometimes, he has a point.

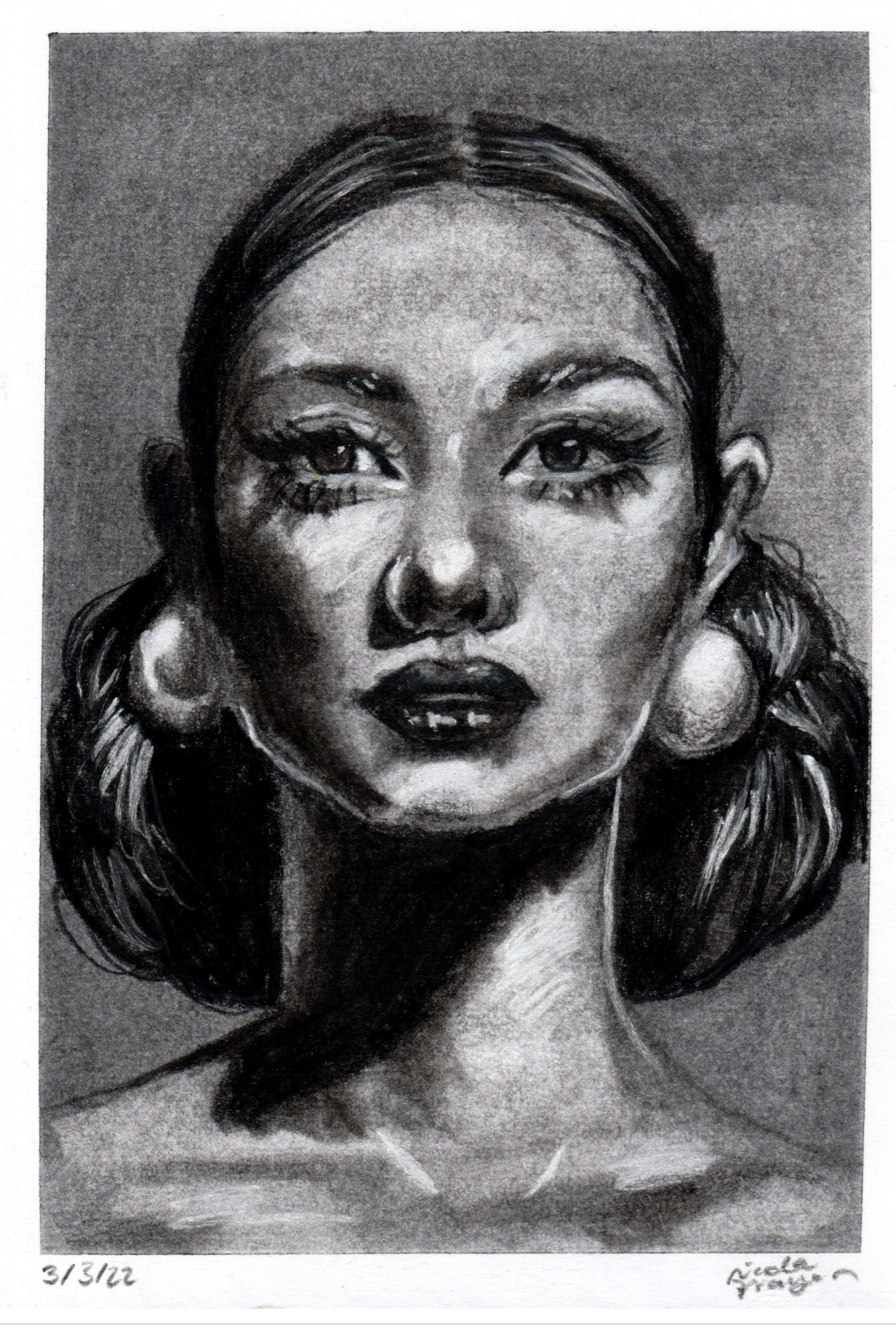

Sometimes Dad’s fuse is so short that the potential consequences of a small slight make no bearing on his actions. Sometimes Dad is all reaction. Sometimes wedding receptions have an angry wife who has to drag her drunk husband out after too many. Other times, a fiancé will feel uncomfortable staring over at her prospective to-be, because deep down, she knows they will never be like the couple that just got married. They are trapped by inability to admit to themselves their red hearts are not so red. She doesn’t want the corsage. She drinks alone and sneaks a smoke from a guest. Then she is back in, dancing with you. All seven or eight, or nine years of you, in your first suit. A haircut has accented your moviestardom, but what wins you the ladies is your dancing. You carve the floor. The wedding DJ remarks on the mic. Look at this kid go. Grandma is seemingly in a better mood after some champagne. A relative of your Aunt’s husband tells you affectionately, that when you’re about ten years older, to give her a call.

Sometimes, after you’ve danced yourself tired, and the stepdaughters start complaining, your Stepmother takes you to the car to wait. Dad is going to help collect the platters, and clean up the folding tables, and leftover cake plates with a few other volunteers from the groom’s family. One of them, slightly drunk bumps into Dad and makes a snide remark. No one heard it, but the two of them.

Sometimes Dad is one snide remark away from jail. Even at the wedding reception for his oldest sister, your Aunt, a sweet woman who first really got you to trust spaghetti, and the richness of tomato sauce. Sometimes Dad’s trigger could be pulled by a fingerless hand. Sometimes, as you and the stepdaughters are waiting in the car, the rain really begins to come down. It is the early afternoon, but the clouds make it look like a mean night. It is time to go. There is a running woman. Your stepmother has urgency on her face and panic for eyes. She is running from the reception hall as fast as her stick legs can carry. Sometimes when you are with your Dad and your Stepmother, something has happened. Sometimes something is going to happen like a pot handle left jutting out on while eggs boil.

Your Stepmother flings the car door open cursing your Dad. She is saying your Dad has gotten into it with someone and he’s about to kill him. She is saying it is one of your new uncle’s relatives. He has said something to your Dad, something most vile that could end his days on a rainy afternoon. The stepdaughters grow quiet. She smells of cigarette smoke, she is frantic. She is searching under the front seats for something. Her hands like scurrying rodents hurtling over the floor mats. You, the stepdaughters, and the whole world are silent. The loudness is the pouring rain on the roof of the car, your Stepmother’s urgency, the banging of your heart in your little suit, the stepdaughters’ absolute fright, so loud that one nears tears, the crash of your Aunt’s special day nearing ruin in the denouement.

Your stepmother touches a blue cigar box under the driver’s seat. It is the kind a boy might keep a rock collection in, or where an old lover keeps letters from her sailor, long since gone. Inside of this box is a gun. A real pistol, like a hero’s. Not blue. No orange tip. Its sound effects with the potential to pluck human beings from the world in an instant. It is heavy. She is saying, your Dad wants to kill this man. Words fling out of her mouth. I’m taking the gun. Do not tell him where I am.

Sometimes your Stepmother runs off into the pouring rain and out of sight, and just like a movie, where the timing of one character’s exit signals the arrival of another, out of the hall comes your Dad, just as your stepmother leaks around the corner of the building, and out of the shot. Sometimes, the synchronism of timing.

He is crashing out of the hall, running full speed toward the car. He is biting his bottom lip. Inside of the reception hall there had been a matador with a billowing red cape. Your Dad is the bull from the Bugs Bunny Cartoon. He is the bull’s choleric eyes. He is the intimidating ring from the snout, the hooves scraping the dirt, the pointed horns angled at death, the immutable stare, and he is right at the driver’s side door, which your stepmother told you not to open.

Do not open this door for your father. I have the keys.

Sometimes you cannot remember whether or not you, being the oldest, chose to unlock the door. You can’t reclaim the memory over the clanging of your heart still stuck there in your tiny little suit. Sometimes you make up what happened next.

Sometimes it goes like:

Dad’s aggression at the driver’s side window scares you into opening the door. Open the fucking door. It sounds something like that. His hands like piranhas under the seat looking for the cigar box. He’s found it. Your stepmother never took it. He’s back off through the rain smelling blood, careening toward the entrance to the reception hall. You are frozen in fear. The younger of the two stepdaughters is in tears. Sometimes the both of them understand even less than you do. Bang. Then, Bang, Bang.

Even the rain grows afraid and goes silent as it falls to the ground. Someone has just hit the mute button on the outside world. Then a woman is heard screaming. Then, several women are screaming, and their screams tear down the doors to the hall. Your Aunt, in all white is running in the rain, her fingers gripping tightly at her skirt, the train of her dress growing grey from dragging on the flooded ground. Black streaks careen down her face. She is lost and running to nowhere.

Sometimes it goes like:

Dad’s aggression at the driver’s side window scares you into cowering with the two stepdaughters in the backseat. Open the fucking door, right now. His hands like boulders as he raps on the window. The rain flings off his eyelashes. He his blinking raindrops off furiously as if he is not already blinded with bedlam. He is a dog with his snout just beyond the slats in the fence, snapping, with its teeth reared. He is a psychotic clown with a laugh bubbling behind a funhouse mirror. He is the man with knives for fingers plunging through the mirror. He is the caretaker with the axe, splintering the bedroom door open to get to his wife and son. He is screaming your Stepmother’s name. The rain is loud. He does not have the gun. The real gun. He’s back off through the rain smelling blood, careening toward the entrance to the reception hall.

You are frozen in fear. The younger of the two stepdaughters is in tears.

Sometimes the both of them understand even better than you do. Sometimes the things they will be forced to witness lay ruin to their childhoods. They will see more men with guns. Men with armored vests, and cargo pockets, and police dogs, and lights meant to scorch eyes and stun, and so many voices yelling that discerning a single one is impossible, and the rhythmic glowing of alternating red and blue beacons blasting through their front window. They will see Dad dragged from the bed and his hands and their mother’s in the air, like on TV. You will be at home with your mother and step-father—the family you actually live with—playing video games and eating pizza every Friday night. You pick out one kid-movie, and one Kung-Fu movie at the video store. You go to Taekwondo, and complain because it seems like a chore after playing all day at school. You race bikes on the cul-de-sac with the neighborhood boys. You go on adventures in the forest just a few blocks from your neighborhood. You splash in the creek and set a fire. You write letters to your crush and go to Disneyland. You record pop songs on the radio and complain to your mom about eating baked chicken again.

But sometimes it is Bang. Then, Bang, Bang.

Sometimes when the stepdaughters relay to you what will happen later, they will say that it was really early in the morning when they came to get Dad. And that as the men with the armored vests and police dogs pulled Dad from the bed, he tried to fight them off. Sometimes when they tell it, he’s pulled outside of the house and his face slammed into the concrete. It is still dark out. They are crying, and the world is loud.

Sometimes the police with the dogs stick the gun to your Dad’s back as his face is smashed into the concrete.

Sometimes they lodge the gun right onto his neck. Sometimes the muzzle of the gun is directly up against the back of his head and his face is smashed into the asphalt. Sometimes there are multiple guns aimed at all of them. None of the guns are blue. They are all always the real thing. None of the guns are blue. None of the guns are blue and plastic and lightweight. None of the guns mimic the sounds of guns. This is certain.

Brandon Diaz currently teaches courses in Literature, English Composition and Rhetoric at San Francisco State University and Los Medanos College. In addition, he’s published several short-stories in prominent and less well-known literary magazines. In 2016 he was awarded SFSU’s Department Award for outstanding academic performance for my graduating MFA thesis, a collection of shorts entitled, Fishing with Sergeant Barbecue. Diaz is an Oakland-based Lecturer and culture writer. He lives with his plants and thoughts.