In The Belly Of The Whale

Adele Evershed

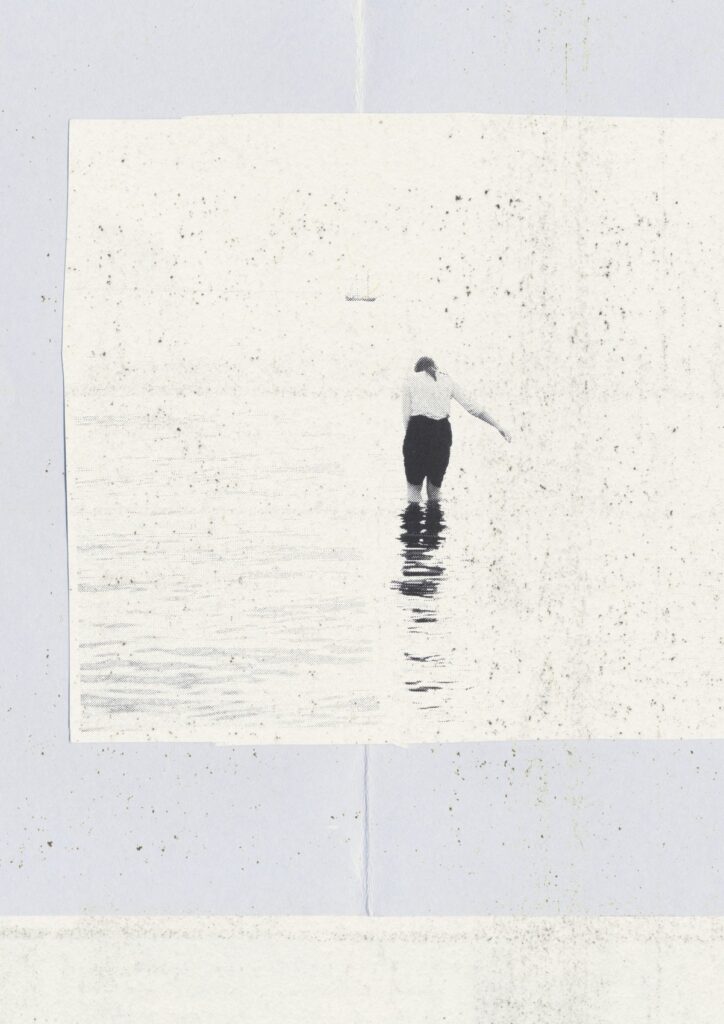

Growing up by the sea the air yellowed everything, the railings of the school, the paint on our house and my mother. When we were young, I taught Gareth, my brother, to lick his arm and taste the salty corrosion bubbling on his skin. I told him we had the tang of the waves because we were selkies and came from the sea. We had lost our seal skins and grown legs, but our father still lived underwater with the whales and fish, which was why he couldn’t visit. And Gareth, with his eyes so dark you couldn’t make out the pupil, and with sea mist frosting his curls, it was easy to believe he was magical.

As we grew, I added to the story. I would take Gareth hunting for our lost skins, looking in rock pools and dank caves. And because they are of the land and sea, seagulls became our messengers. We would shout at them to tell our father we still loved him. Now, I know Gareth never let go of that feeling; his instinct stayed inside out, longing for something he could never find.

On those blue-grey days after our father disappeared, Mam would pour stories from the teapot. She always served Gareth first; he’d drop in a sugar cube, like a pebble, and make a wish as the rings rippled outward. My favorite tale was about the old witch who lived in Kenfig Lake. I’d listened wide-eyed as Mam told us how she wanted to regain her youth by drowning the children that never listened to their parents. And if we’d been cheeky she would say, “You know she needs nine hundred to get her wish? Well, last I heard she only needed two more so mind yourself now”. Gareth my brother always protested that he could swim so that old water hag would never get him and then he’d beg for the story about Meridog, Prince of Whales.

Mam would slow her voice and say, “Once, so long ago Wales was a kingdom there was a Prince whose song could magic up trout or lobsters, oysters or pearls. So his people were never hungry, and for that, they loved him well. His name was Meriadog, which means head of the sea. Everyone was happy apart from”, here she would pause so we could shout, ” Dark Dylan, God of the Sea,” and Mam would look almost happy.

When we were got older she would let Gareth finish the story. He would deepen his voice and say, “Old Dylan was jealous, so he sent a wave to sweep Meriadog away. His sister, Bronwyn, was heartbroken. She went to Dylan and begged him to save Meriadog’s life. So, Dylan let Meriadog live in the belly of the whale but in exchange, Bronwyn had to promise never to leave the sea. Then the whale could come back one day a year, and Meriadog could go ashore. After the story, the teapot would be cold, and Mam would strip the tablecloth to wash away the stains. It’s only now I realize Mam never told us what would happen if Bronwyn broke her promise.

Later, when I went to live in the city, Gareth stayed behind. Yet, he never seemed to hold down a job or a girlfriend for more than a month or two. Then, finally, he told me that he couldn’t fill up his empty spaces no matter what he did. So I joked he was still searching for his sealskin. I should have rescued him from the clamor of the waves, but I was selfish and too full up with what I thought I knew.

When Gareth went missing, Mam always set a cup for him in case he just showed up again like the rain. At first, we spent long hours looking for him and pestering the police. Later we sat silently drinking lukewarm tea and slopping brown splodges like dirty tears on the tablecloth. Mam never bothered to bleach them away and I never left the sea again.

I lay the table with her tablecloth; those tea age spots match the ones on my hands now. I set a cup for me and one for Gareth. I am the one who is yellow now—weathered from a lifetime spent watching the sea. When I was little and people told me I lived in Wales, I imagined we were a people like Jonah or Meriadog. I pour the tea with the weight of our unfinished story and make a wish on a sugar cube for my brother to be safe inside that warm bellied world, lulled to sleep by the ocean until he can be brought back home to me.

Adele Evershed was born in Wales and has lived in Hong Kong and Singapore before settling in Connecticut. Her prose has been published in over eighty online journals and print anthologies such as Every Day Fiction, Free Flash Fiction, Ab Terra Flash Fiction, Grey Sparrow Journal. Her poetry can be found in High Shelf, Tofu Ink Arts Press, The Fib Review, Wales Haiku Journal, Shot Glass Journal, Selcouth Station, Open Door Magazine and Hole in the Head Review. Adele has recently been shortlisted for the Pushcart Prize for poetry, the Staunch Prize for flash fiction, and her novella-in-flash, A History of Hand Thrown Walls was shortlisted in Reflex Press Novella Contest.