Blackberry Winter

Adele Evershed

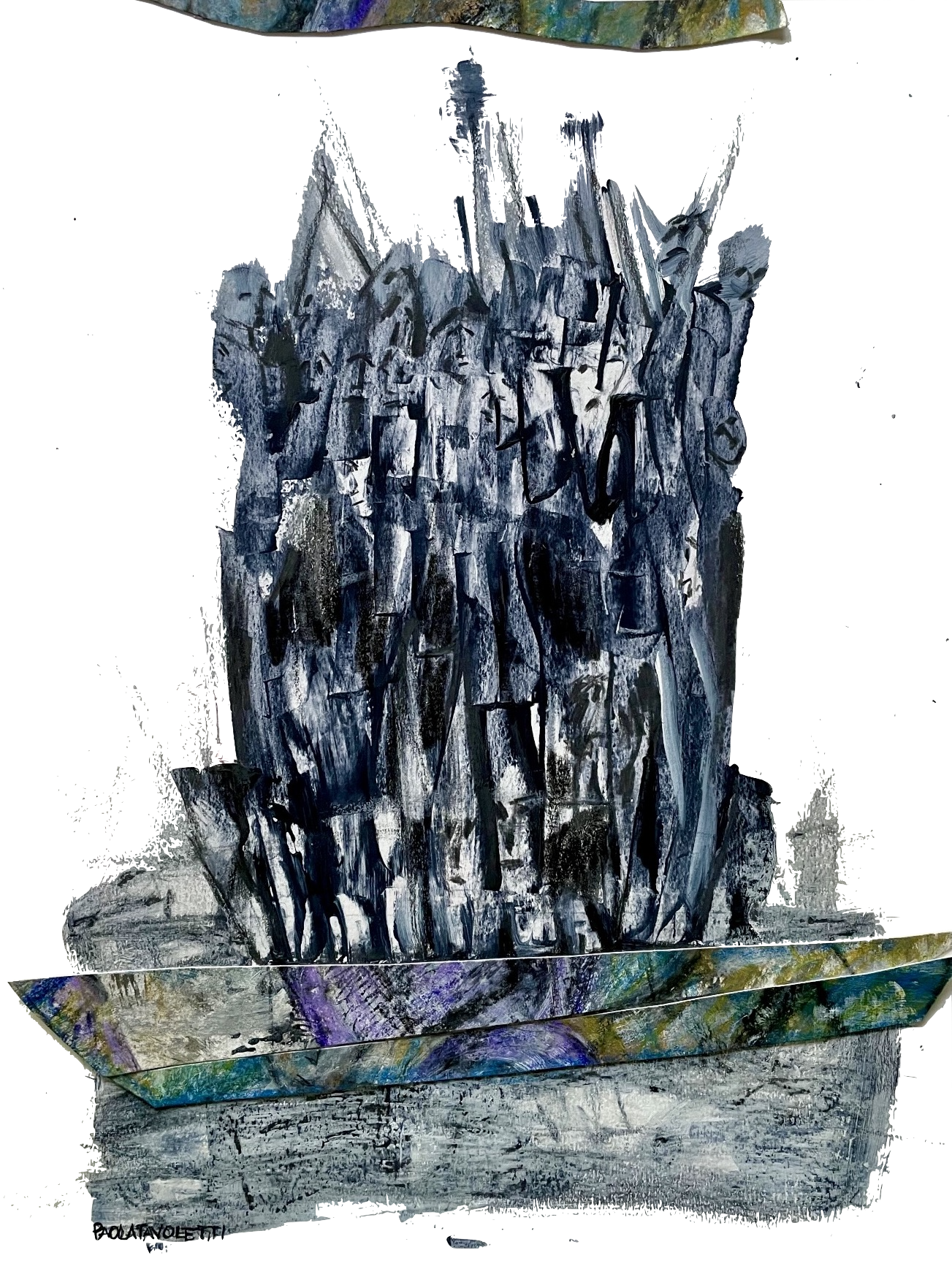

We all knew Bernie was dead. Papa had even dug a hole next to Johnny’s grave beside the low slung wall of stones that bound our small patch on this earth. When he came in, he took off his work boots and told Mama, “Johnny will be a good big brother and look after our baby girl until we all meet in heaven, God willing.” Mama didn’t say anything; she carried on rocking Bernie in the cradle as if she wasn’t already engulfed by her eternal sleep. Slowly Ma picked up a rag to clean off the clod from his boots as if Papa might need them to go back out to work soon. But Papa’s job like Johnny had been gone for a long while now.

The following day Mama peeled herself from her chair and spruced up the house as if we were expecting company. Then she turned her attention to my brothers and me slicking down their hair and saying to me, “May bug git yourself outta those raggedy pants and put on your best polka-dot dress.” When none of us moved, she snapped, ” Hurry now. Why are you lolling about like a puddle of long sweetening? ” Papa took her gently by the shoulders and tried to lead her back to her seat, but she shook him off like a shower of rain.

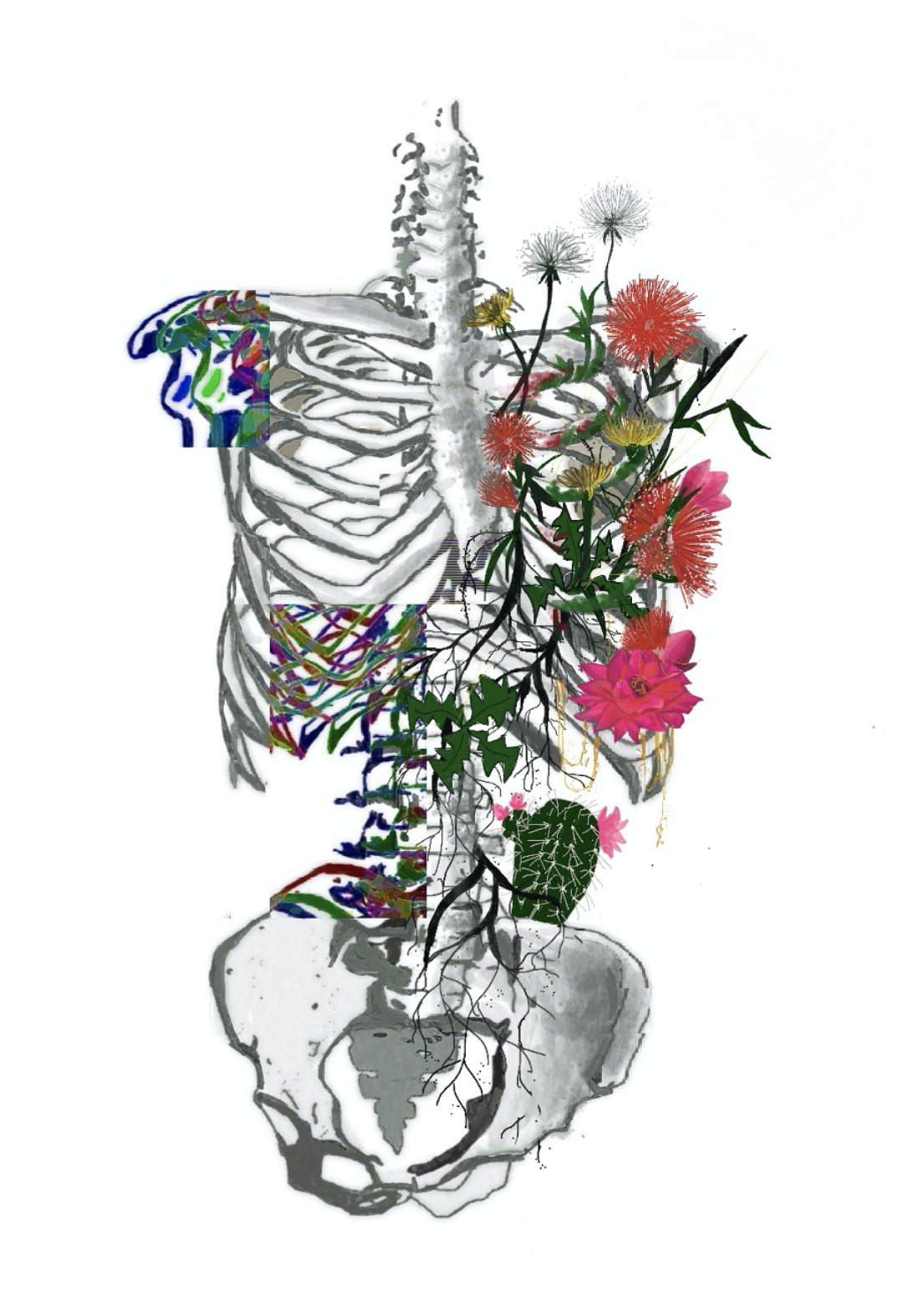

Mama looked sideways at him and shuddered as if she was breaking from the inside out. And then she unpacked her black dress, the one she kept wrapped in plastic. The rustling made me think of the wren that had flown into our house the week before Bernie passed. Mama had taken the broom to it, stunning it, and as I watched, she hit the wee mottled bird with the cooking pan. I let out a squeal like one of the wild piglets, and Mama turned to me, her eyes like foxfire, and said, “Oh May bug, I needed to git it before it could get word to God.” Teacher had declared all these old beliefs just superstitions, but I could see Mama was scared. She believed if a bird flies into the home, someone would die. After my sister, Bernie, passed, I never put much store by what Teacher said ever again.

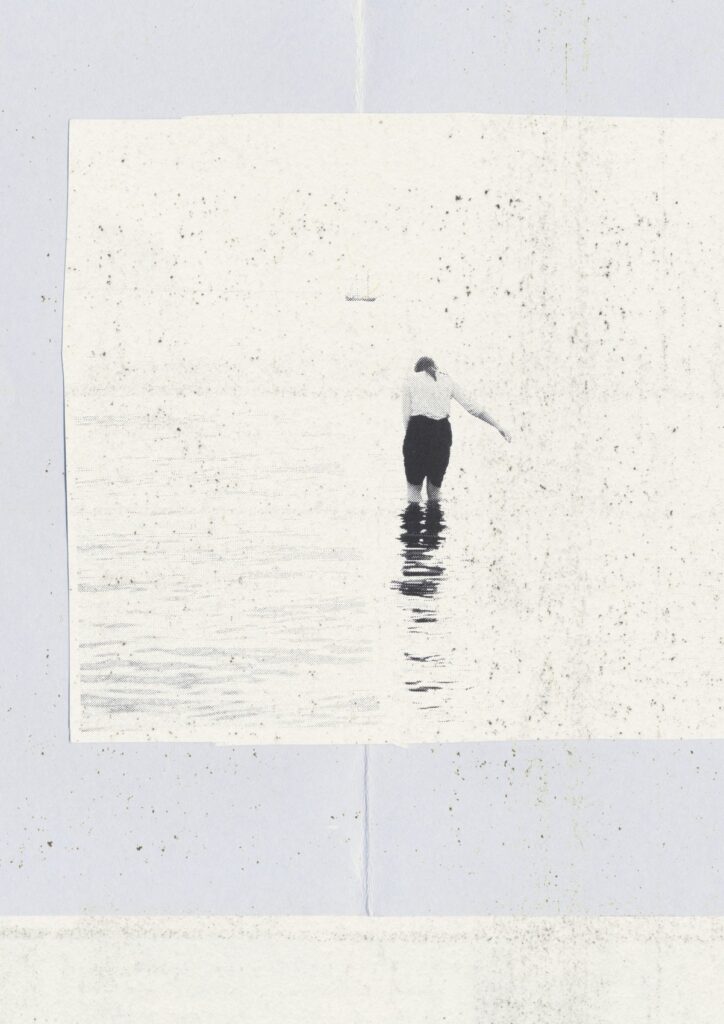

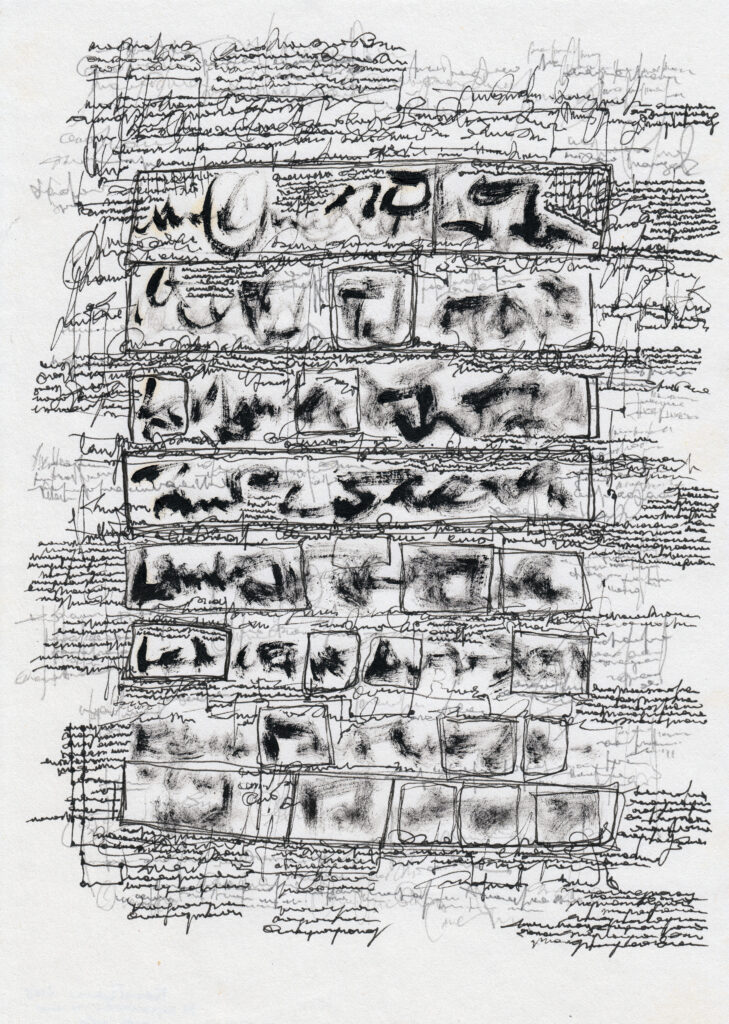

Mama stood up straight as if she was addressing the Reverend and said, “I’ve been a-studying about how to say this till I’ve nigh wearied myself to death. Mary-Jo told me….” Papa interrupted, tutting, “Now that women’s tongue’s a mile long. I put no store by any of her wild tales,” Mama continued as if he hadn’t spoken, “There’s a man taking photos for a New York magazine in the Cove. He’s already been to the Mobley’s to photograph poor wee Riva. You know she’s backset with the measles”. Papa stretched his neck as if he had a crick, “I hope you ain’t saying that mule trader is bringing himself here?” His voice had deepened, and his eyes were like chips of coal. I could feel the waspers in the air that Papa could let loose when he was vexed and backed against the wall. My brothers, skittish, came to join me. I took my lucky white stone out of my pocket and gave it to Cooper, my youngest brother to try and distract him. But although Mama peaked, she said, “I allowed he’d git here this afternoon.” Mama picked up Bernie from the cradle and started to sing a lullaby as she dressed her in the white coat and matching booties she had knitted not a year ago.

This was the only time I ever saw Mama defy Papa, and it not end in a whopping. The man from Time Magazine came and took our photo. It was a blue cold day when he crossed over Line Fork Creek on the rickety bridge to our two-room shack, but at least the temperature meant he couldn’t smell the sewage frozen in the water. Papa told us all not to smile, said it wouldn’t be proper. And he refused to put on his boots or put out his roll-up.

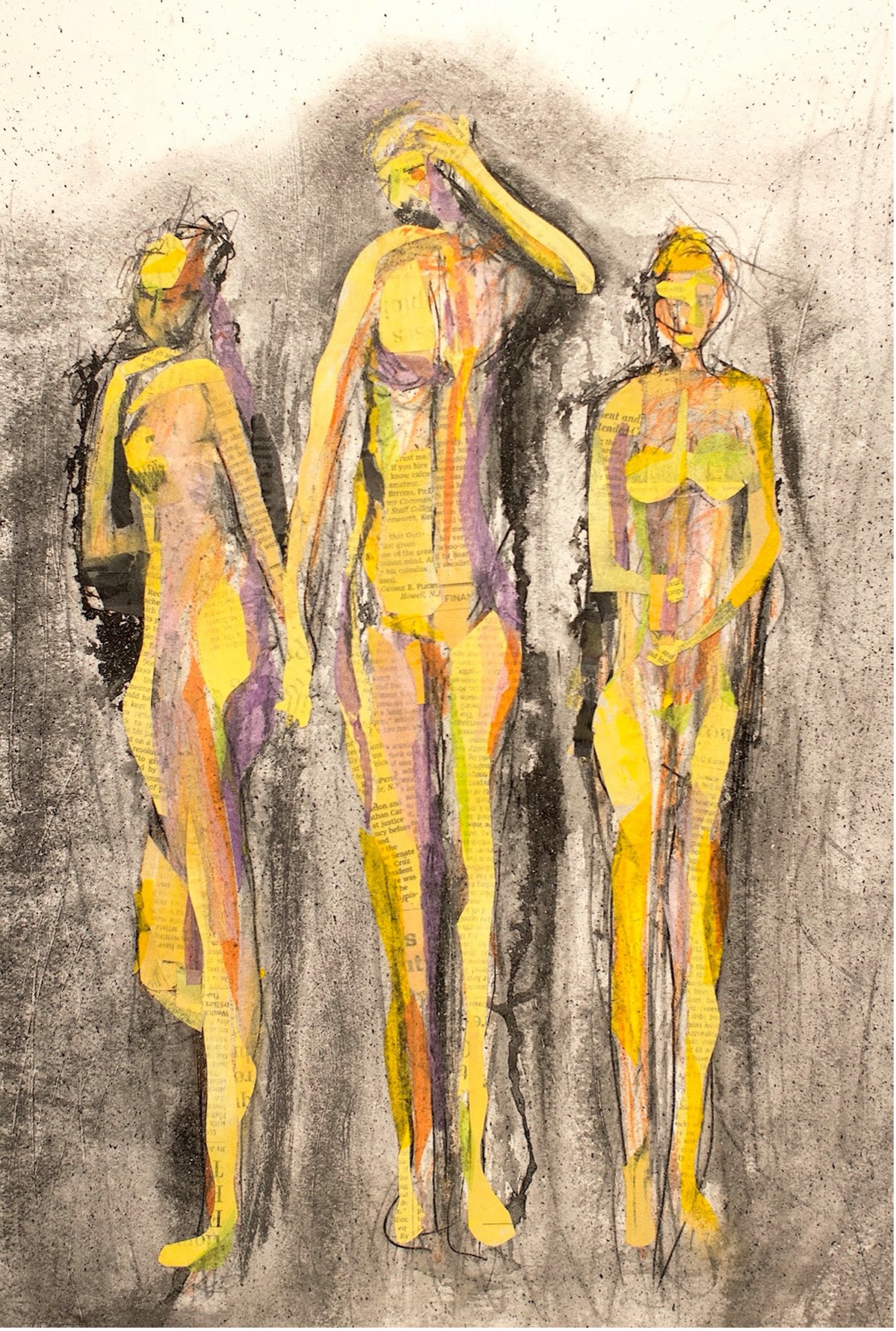

Later, Mary-Jo cut out the photo and brought it over for Mama. When Papa saw it, he took the belt to Mama, leaving her with indigo bruises up and down her arm. All that winter, Papa raised welts on Mama; they sprang up like clumps of blackberries on the forest of her body. And like a forest Mama stayed silent, letting the fury pass over her like the wind.

Papa never said why the photo made him so vexed, but I think it was because Mama was smiling, and he knew nothing we could do would ever make her smile again.

Adele Evershed was born in Wales and has lived in Hong Kong and Singapore before settling in Connecticut. Her prose has been published in over eighty online journals and print anthologies such as Every Day Fiction, Free Flash Fiction, Ab Terra Flash Fiction, Grey Sparrow Journal. Her poetry can be found in High Shelf, Tofu Ink Arts Press, The Fib Review, Wales Haiku Journal, Shot Glass Journal, Selcouth Station, Open Door Magazine and Hole in the Head Review. Adele has recently been shortlisted for the Pushcart Prize for poetry, the Staunch Prize for flash fiction, and her novella-in-flash, A History of Hand Thrown Walls was shortlisted in Reflex Press Novella Contest.