Your Dreams

Dave Newman

Wayne parks the motorhome in the driveway and walks to the front door. He spent two years picking this one out, a GM Rector with extra storage and new tires. Refrigerator with a bottom-loading freezer. The curtains look like something from a dollhouse, pretty pink with burgundy flowers, his wife’s favorite color combination.

He forgot his key and pushes the bell and waits.

His wife opens the door in her robe, a plastic cap on her head, smelling of hair dye. Her cane loops her arm. He bows like an old-timey gentleman, which he is. Fifty-three years of marriage. The jokes come slower but he keeps telling them.

“Straighten up,” his wife says. “Don’t bother me when I’m doing my hair.”

Wayne un-bows.

Neither he nor his wife move well anymore but he tries every day.

She tries when he insists but he hates insisting and the fights that follow.

He guesses he walked thousands—maybe millions—of miles on his knees, pulling wire, putting in sockets and gauges. Now he can barely straighten his neck from arthritis. Knees too. All his fingers. The humidity makes it worse, and the winter. He wakes and his aches play on repeat. His wife moves like a rusty winch and complains but refuses change, even suggestions. She spends days watching old gameshows on her computer. He brings her dinner on a tray.

They started as kids in West Virginia. Then Virginia. Then Kentucky for a couple months, where he worked with reactors. Then Western Pennsylvania and they never left. Wayne loves the green trees and the mountains and he’s fished every stream in the Laurel Mountains. All his wife’s sisters are gone, and his last brother lives in Arizona with the dry heat. When they visit, he can feel his body in the oven, baking itself back into place. His neck barely hurts in the desert. His fingers straighten so he can write in his old yellow notebook. He sometimes writes letters to his dead parents, thanking them.

Now his wife says, “I knew you’d forget your key.”

Wayne says, “Do you remember when I proposed and gave you that metal ring when we were sixteen back in Beckley and I said I’d replace it with a good one?”

She raises her hand to show the replacement ring, the diamond he saved ten years to buy.

She says, “It still twinkles.”

They lived in a cabin then a trailer then over a hamburger restaurant. He worked in the mines then a lumber yard then the reactor then a mill here in Pittsburgh until he started his electrical business. He still owns the van and his tools. He still fixes things for people at church who can’t afford fixes. His wife sold houses. Won all the awards. Got a free cruise and a trip to Hawaii and she took her sisters. Then quit one day for no reason and stayed on the couch for thirty years. He wanted her to work. The money was good. A life outside the house was better. But she wanted to watch TV. Then the internet. She drank Pepsi like it was medicine until the doctors made her stop. She worried when her sister caught muscular dystrophy. She worried when her mom got old, her dad older. She prayed for them all, eyes closed, TV on.

Wayne thinks she dreams of heaven, of golden streets and a reunited family.

But he has these years he worked for.

He still smells grease from the lumberyard and remembers the mine, blowing black snot into a rag. He’d like to live near his brother, in weather that helps his bones. He says something like that to his wife every day, a reminder that he is still here, still dreaming of things other than an eternity in paradise.

She says, “I saw you pull up in that monstrosity.”

“It’s got dollhouse curtains,” he says, “in your favorite colors.”

She adjusts her cane. Then she slides it down her arm and braces herself, leaning on the handle, pushing on the floor.

She says, “My mother died in this house. She come up from West Virginia so I could take care of her. I took care of Vee when she got so bad she couldn’t swallow. My sister Edith died here and so did her husband, three streets down. I was with them both.”

He says, “I know where my in-laws lived.”

She says, “You brought us here.”

He says, “We came here together. We lived our dreams.”

“Your dreams,” she says. “Your key is on the kitchen counter. Quit forgetting things.”

He touches his neck, feels the vertebrae.

He says, “I loved your sisters. I was the one who drove down and brought your mom here. She couldn’t have found Pennsylvania on a map. I went down and stayed with your daddy when he was sick. I fixed up that bed so he could recline, so he could sit up and watch his shows.”

She turns and takes the stairs, two feet on every step then her cane.

Wayne always thought dying your hair was vain.

He never liked makeup either.

He walks back to the motorhome and climbs both steps, feeling his knees. He starts the engine. The air conditioning blows his hair, what’s left down front. He feels the steering wheel, the plastic that looks like brown leather. They have pills now so the men can keep having sex. He’d try that. See a doctor. Dance around the bedroom. He still feels the heat, still thinks of his wife. He guesses she wouldn’t care either way. He straightens his left leg and puts his right foot on the brake. Everything is paid for. He filled up the tank on the way home. He stopped at Walmart and parked out back with the big trucks and he bought snacks and loaded the refrigerator with cans of diet cream soda, his wife’s favorite now that she can’t have sugar.

Dave Newman is the author of seven books, including the novel East Pittsburgh Downlow (J.New Books, 2019) and TheSame Dead Songs: a memoir of working-class addictions (forthcoming fromJ.New Books, Summer 2022). He lives in Trafford, PA, the last town in theElectric Valley, with his wife, the writer Lori Jakiela, and their two children. For the last decade he has worked in medical research.

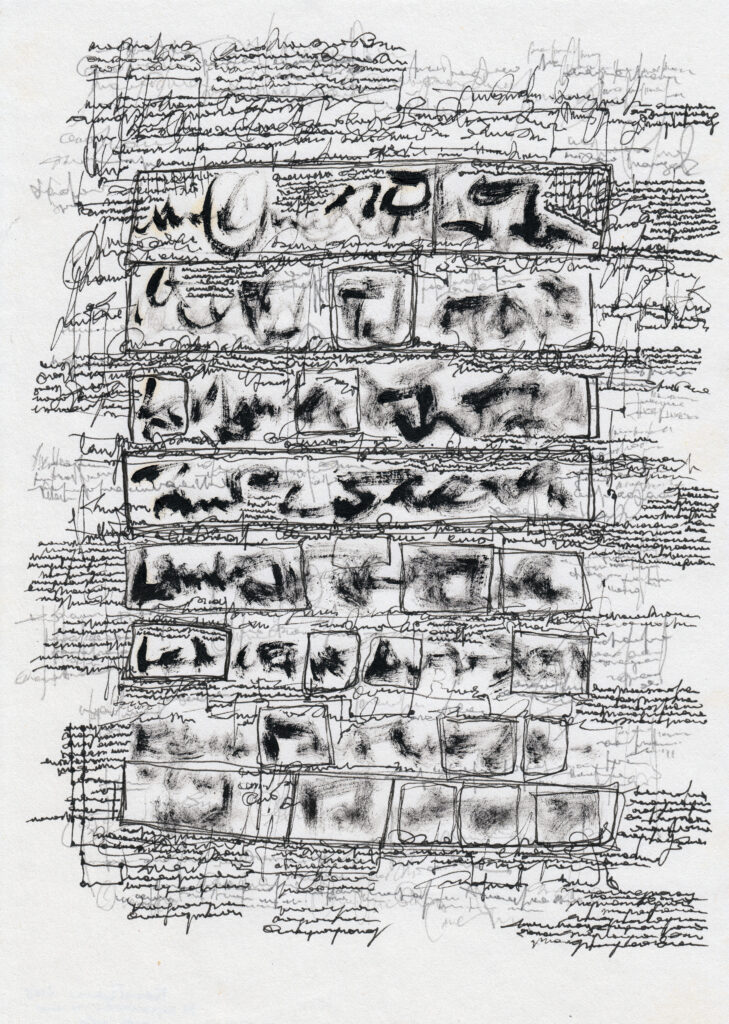

Art: Birds, Yellow Sky by Christopher Woods who is a writer and photographer who lives in Chappell Hill, Texas. His photographs can be seen in his Galleries: https://christopherwoods.zenfolio.com/f861509283

https://www.instagram.com/dreamwood77019/. His photography prompt book for writers, FROM VISION TO TEXT, is forthcoming from PROPERTIUS PRESS. His novella, HEARTS IN THE DARK, was recently published by RUNNING WILD PRESS. His poetry chapbook, WHAT COMES, WHAT GOES, was just published by KELSAY BOOKS (kelsaybooks.com).