Vero and Jesse

Christopher Williams

Vero slid down a hole after her mother died. Life in the hole was dusky and out of focus, so she wandered around her childhood home, ambling from room to room as though she’d misplaced something, a water glass maybe, or a set of keys. But she hadn’t lost anything she could recover; she simply paced because sitting still forced her deeper into the hole.

She resurfaced a month later, surprised to find she had a guest in her mother’s room. No longer submerged in the inky waters of recent loss, she inspected the whole house, finding evidence that the guest had been there for some time: a razor in the bathroom, a mixed martial arts magazine on the kitchen table, two large duffle bags of clothes by the closet in her mother’s room, and a black oxford hanging from the curtain rod. A room not truly settled into is a lonely sight, but Vero was relieved that whoever it was hadn’t taken over her mother’s drawers and closet.

As she was gazing through her mother’s bedroom window, wondering how she could’ve missed having another person in the house, she spotted him. He was sitting on the back patio, smoking a cigarette and rubbing his eye with the heel of his hand. She knew him. They had dated, or, more accurately, they had gone out twice and then settled into a weekly hook-up schedule. He was a bartender at the Mexican restaurant Vero and her mother had frequented. His thick black hair shone with gel and he had always sent free drinks over to their table. She never in her life would’ve dated a man who wore gel in his hair, but the complimentary margaritas, the bushy eyebrows, the cavernous dimple on his left cheek, and the mere warmth of his presence had been more than enough at a time when the only person in her life, the only actual person, was dying on her.

She remembered now. He’d told her about a dramatic falling out he’d had with his roommate, and she’d told him off handedly that he would’ve been able to stay with her if it weren’t for her ill mother. Looking out at him now as he stubbed his cigarette out on the armrest of the patio chair, she realized that the type of hypothetical generosity to which she’d always been prone had finally come back to bite her.

She retreated to the kitchen and tried to remember his name. Her memory flashed to his colorfully decorated name tag, one of the many festive signatures of the Mexican restaurant. Standing next to the purring refrigerator, she read the memory out loud:

“Jesse.”

“There you are.”

He came into the kitchen buttoning up his work shirt, the black oxford she’d seen hanging in her mother’s room. The gel in his hair reflected the sunlight creeping through the kitchen window. He seemed otherworldly, even slightly angelic as he stood in the golden light particular to that part of the house at that hour. She meant to ask him a whole slew of questions about his presence, but was stopped short by the sight of him bathed in afternoon warmth, smiling so widely that the dimple on his left cheek appeared deeper than the hole she’d just crawled out of. What’s more, his arms were spread wide for a hug, and as she stepped forward she was momentarily blinded by sunlight. Once inside his orbit, however, his wide shoulders shielded her eyes from the light. It was the first physical contact she’d had since the funeral. She suspected it was false, of course, but that did nothing to lessen its effect.

*

After the diagnosis, Vero decided to accompany her mother to church for the first time in years. She weighed the decision carefully; the last thing she wanted was to give the impression that she’d regained her faith. But the thought of frankincense smoke and stained glass windows overrode her caution. She hadn’t experienced those sensory cues in years, and she knew they would put her in touch with a version of herself that took her mother’s immortality for granted.

They sat near the front in a wide ray of sunlight where dust motes bobbed in otherwise imperceptible air currents. Vero heard nothing of the sermon, didn’t look down at her hymnal once, but instead basked like a lizard in the spring sun that felt somehow different, she might’ve even said holy, shining as it did through the stained glass Immaculate Heart.

Afterwards, they sat outside at a favorite breakfast spot and watched couples not much older than Vero walk their dogs and toddlers. The sun filtered through the branches of a freshly blossoming cherry tree. They didn’t say much, aside from Vero’s mother occasionally sighing, “This is nice,” not from a lack of anything to say, but because it was, in fact, really quite pleasant.

“Remember this,” she said, making a motion with her hands that, despite being slight, clearly indicated the whole world, and even beyond. To Vero, her mother’s hands suddenly looked like those of an old lady, complete with liver spots and paper thin skin. She closed her eyes and concentrated on the sun’s warmth. She heard her mother’s next words as though in a dream.

“When I’m gone, you still have to get out. I mean, look at all of this beauty.”

Vero nodded. She knew her mother was editing God and Jesus out of this talk for Vero’s sake. This was another one of her countless concessions to her daughter, and the graciousness of it grated on Vero. She had always been one to roll her eyes when her mother said she would pray for her; had always looked askance at the books with pastel covers and titles that suggested God was close by, next door, or even across the kitchen table; she had once even scoffed out loud at an angel figurine her mother had sent her in the mail, as though it was so important that it couldn’t wait until the next time they saw each other. Now, of course, Vero realized she’d been insufferable.

“Try to get out into the light,” her mother said.

The sun now lit up Vero’s closed eyelids to a shade of red that, she had to admit, bore more than a passing resemblance to the stained glass Immaculate Heart. She nodded in a way that she hoped displayed both respect for, and yet distance from, her mother’s beliefs.

“I’ll try,” she said.

*

She needed to talk to someone about Jesse. The only person she’d connected with since she’d moved back was a girl she’d known in high school named Renee. They hadn’t been friends then, not really, but they’d run in similar groups, and when Vero had first moved back Renee reached out with a message on Facebook,“Welcome back to Limbo!”

They quickly became the type of friends who required little pretext to spend time together. They ran errands, watched awful reality TV, and went out to eat whenever they didn’t feel like cooking, which was often. At 25 they had given up on the hallmarks of their age: partying, exotic drugs, drinking as religion, complicated romantic entanglements, and anything that could be reasonably considered a “scene.” They had long since diagnosed themselves with an early onset allergy to crowds.

They met up for coffee on the plaza, and Vero quickly realized that this particular meet-up had been a mistake. Renee took seriously her responsibility to help her friend process the loss of her mother, which was noble, but it was also exactly what Vero did not need. She had grieved, in her own way, and now she just had some questions she needed to talk through. She knew, however, that if she brought up Jesse she’d be robbing Renee of her right to play her role as the supportive best friend. So instead Vero went through the motions, talking about the emptiness of her mother’s home, all the while thinking of its non-emptiness, of the person who’d come, in some sense, to replace her mother.

Vero struggled to keep track of the conversation. It was already hot even at that early hour, and would easily reach 100 in the shade by early afternoon. On such days, Vero and her mother had often retreated to the coast for fish and chips and bags of salt water taffy. The vibrant collection of ridiculous candy would then sit on the kitchen table for days afterwards, and although Vero had never actually liked the taffy, she’d always appreciated it as a way of holding onto the drive out to the coast, to the cool moisture of the Pacific on her face and forearms, to the relief they’d found from the sadistic heat.

Vero finished her coffee quickly. Renee invited her to lunch, but Vero begged her off, saying she was just going to lie low at home to escape the heat. The second she crossed the house’s threshold, she could tell something had shifted. It was still morning, so the rooms were shadowy, and because it was bright outside and she never wore sunglasses, it took her a moment to adjust to the darkness. She circumvented furniture and walls from memory, and it struck her that this must have been exactly how she’d looked during her month of mourning, though now she was actually looking for something. His name, at least she thought so, was Jesse. But he was gone, along with every trace of him. No razor in the bathroom, no magazine with a baroquely tattooed ectomorph on the cover, and no overflowing duffle bags in her mother’s bedroom.

Not knowing what else to do, she slumped onto the couch to begin an hours-long assault on her brain with the shimmering sledgehammer of daytime TV. Ostensibly she was watching the game shows, soap operas, talk shows, and small claims court dramas play out, but really it was the commercials that were the most therapeutic. They had changed very little since her days of staying home from school for a range of imagined symptoms. True, production values were better now, the General looked spiffy in computer animation, for example, but in many ways the pleas to invent something, to purchase life insurance, to contact a personal injury lawyer, to buy a button that called 911 for you if you face-planted in the garden, to enroll in a for-profit university and become a dental assistant, to call if you’d received a mesh implant as part of a hernia surgery between 2003 and 2007, they were all basically the same. The message being, you are home and the sun is shining, people are out making money and learning skills in life, therefore you who remain stuck to the couch are either decrepitly old and/or hopelessly useless to society.

Vero couldn’t argue with that. Even before her mother’s death she’d been merely treading the waters of adulthood. Most days, making rent in San Francisco off hostess wages had felt like enough of an accomplishment. But there were times, possibly triggered by her addiction to daytime TV, that she’d felt she should do more, should want more. When her mother developed chronic headaches with no relief and a brain scan revealed a tumor, Vero was actually relieved to move back up north and be of some use to the world. She had imagined herself in flowy white clothes, tending to her mother in the gauzy afternoon sun that shone cinematically through the bedroom window. She would feed her mother little spoonfuls of chicken broth and wipe her chin clean with a white hand towel. She had assumed her mother would get better after a month, maybe two, and that her own efforts as caregiver would be, if not the main cause of the recovery, at least a strong contributing factor.

Of course, nothing turned out as Vero had imagined. For one, she’d never even gotten a chance to buy the chic minimalist clothes of a sophisticated art gallery owner; after she’d moved in, the dying process lasted only as long as three laundry cycles. A week after Vero had arrived, her mother went completely blind. A week after that, she could no longer get out of bed. She became incontinent and hospice took over. Two weeks after that and she was gone. It all had the feeling of a hit and run, or a drive by, or being shot in the face while turning a corner. Vero didn’t have the exact image it corresponded to, but it involved speed and flying metal and a body destroyed; she knew that much.

It was during the period that would’ve corresponded to the second load of laundry that Vero had taken up with Jesse. Some of it, she had to admit, was due to her mother’s encouragement.

“Oh honey, he’s adorable.”

He had all the qualities that would appeal to a mother, and the fact that he spoke glowingly and with almost disturbing frequency about his own mother actually reassured Vero. This is a crossing guard of a man, she’d thought.

*

She awoke on the couch. Were it not for Frank Sommers reading the five o’clock news, she would’ve had no decent guess as to the time. She’d known where she was even before opening her eyes, however, because the smell of her mother’s home was impossible to confuse, even in her sleep. The weatherman motioned to seven yellow suns lined up like trophies, and Vero wondered if the smell would fade, if it was particular to her mother or to the house itself. She couldn’t decide which she would’ve preferred, though for the moment the smell proved comforting.

Jesse came into the living room in his work clothes, eating a bowl of her cereal. He was hard to make out. The afternoon light was always dim in the living room, and the TV gave off only a faint glow. Because she was the type of person who had to turn off the radio to parallel park, she muted the TV to help herself comprehend the reappearance of a man who, she now realized, might be the realest person in her life.

“You’re back,” she said.

He cocked his head at her and sat on the couch. They looked at each other, for how long Vero wasn’t sure, but something about his easy smile and her own lingering sleepiness made her lower her head slowly onto his lap where he stroked her hair slowly, from root to tip, just as her mother used to. Her last thought before she fell back asleep was that he smelled like nothing, or, at most, like a warm breeze. All she could really smell was the house. When she awoke this time Dennis Richmond was silently mouthing the ten o’clock news. She wondered if it had all been a dream, but that was impossible, after a certain age she’d lost the ability to remember her dreams. Either way, she could sense that she was alone again.

*

She came up with a sort of plan. She invited Renee to the Mexican restaurant for dinner and arrived early to get a table with a view of the bar. When Renee arrived, there was still no one manning the bar, and Vero kicked herself for suggesting such an early hour. When the waiter came to take their orders, she said she was fine with chips and salsa and a glass of water. Renee took this to mean that her friend just needed some company and an excuse to get out of the house; she offered to let Vero stay with her for a while. Barely listening, Vero thanked her friend, intent on not missing the appearance of Jesse at his post. When a short, heavyset man with curly hair took up the spot behind the bar, Vero buried her face in her hands.

“What is it?” Renee asked, turning around to see what had caused the reaction, “Do you know that guy?”

“I’ve never seen him before in my life.”

She was silent for the rest of the meal. Renee tried to cheer her up with a story about a recent date. She told Vero all about the date’s appearance, job, and interests; all the statistics you recite to yourself when you’re considering sleeping with someone, but all Vero could think of were things she’d rather not say.

For example, her mother had been the only one in Vero’s life to meet Jesse, on a night when he’d picked her up to go to a terrible comedy he’d picked out. Vero had told him to text upon arrival, but he’d rung the doorbell so that he could escort her to his car and force everyone to know what a gentleman he was. But he then charmed the pants off Vero’s mother, making her laugh with some of the corniest jokes Vero had ever heard. Despite herself, she too found herself laughing. Any levity in those days was more than welcomed. But now Vero wondered at this supposedly happy memory. Was a memory happy if you had no one to share it with? Was it a memory at all? These were the things on her mind, topics she wouldn’t broach with Renee for anything in the world.

*

The edges of her vision had started to fade while they were still at the restaurant, and Vero felt an overwhelming need to return to her mother’s home immediately. By the time the bill was paid and they were walking to their cars, spots in the middle of her field of vision were starting to fade to black as well. She had no problem hiding all this from Renee; they were not that close after all, and had only ever really wasted time together, playing out the clock until something happened in their lives. For Vero, that time was now, and as she hugged her friend goodbye, a more final farewell than Renee could’ve imagined, she was reminded of her mother’s blithe acceptance of going blind, and how it wasn’t actual disinterest at all. Her mother had viewed her failing sight as a sort of blessing.

“At least I don’t have to watch you suffer anymore,” she’d said.

Similarly, Vero was glad she didn’t have to see Renee’s face at that moment. She could not have abided the look of sympathy, or worse, pity, that her friend was likely giving her right then.

The nearly blind drive home would’ve been harrowing had Vero cared what might happen to her. If she were to die now, she reasoned, her life would have had meaning. She had taken care of her mother in her last days, and once that was taken care of, she had exited this world gracefully. Whether a fatal car crash qualified as a graceful exit was debatable, but she wasn’t going to worry about that.

Her sight was completely gone by the time she walked through the front door. Without needing to turn on the lights she glided calmly to the living room and sat on the couch. Perhaps in an attempt to further channel her mother’s unwavering acceptance of all of life’s twists and turns, Vero thought of all the money she’d now be able to save on the electric bill.

“You’re back,” Jesse said, calling out from the kitchen. She heard footsteps and then the groan of the loveseat as he lowered himself into it.

“How was it?” he asked.

“Can I ask you a question?”

“Of course.”

“Do you even have parents? I mean, you’ve talked about your mom a lot, but is she still alive?”

“Everyone has parents. Mine are still alive.”

“I just don’t understand what’s going on. You’re living in my mom’s room, apparently. Or maybe not. I should stop talking. There’s nothing to say. When people die there’s nothing to say.”

“No, it’s okay. It can help to talk.”

“I wish I could see you. Even though I don’t really know you at all.”

“I understand.”

“Do you?”

“Would it help if I told you what I see?”

“I don’t know. Try.”

“A young woman sitting in her mother’s living room. There’s moonlight coming in through the window. She’s staring at nothing, because she can’t see at the moment. But it’s temporary, because everything is temporary.”

“You can see that?”

“It’s plain as day.”

Vero tried to picture it, partly because she was now terrified by the totality of the darkness, and partly because her mother would’ve wanted her to at least try. But sometimes things simply went dark, and you had to accept that. She could see that now. When she spoke again, someone might be there. Or not. It made no difference.

*

Vero awoke the next morning to the jubilant smell of her mother’s jasmine perfume and the earthy smell of her unwashed hair. She had no memory of making her way to her mother’s bedroom the night before, but here she was. The window was open and the crisp smell of the neighbor’s freshly watered lawn filled the room. She realized that her sight was back, and she was relieved, but burying her nose into her mother’s pillow and inhaling what was left of her smell was her more immediate concern.

It was still early, but it was already obvious that it was going to be another punishingly hot day, and sure enough it soon grew too hot in the bedroom to keep sleeping. She got out of bed and her first thought was to use her regained sight to search out traces of Jesse and settle that matter once and for all. But this option didn’t appeal to her in the same way it might’ve during the previous days. She assumed this was due to the deep, restful sleep she’d gotten in her mother’s bed, her first solid night’s sleep in months. Of course, there was no way she could know that she had dreamt of her mother. And even if she had been able to remember her dream, there wasn’t much to this one: her mother had simply come into the bedroom and sat down on the edge of the bed to watch Vero sleep. The look on her face had been perfectly neutral, but because it was her mother, also loving.

Awake now, Vero stood on the carpet in her mother’s room, unsure what to do with herself. She stared at the curtain glowing yellow with the early morning sun. The heat was building, steady and mindless. She decided to drive out to the coast. With no memory whatsoever of her dream, Vero assumed the idea was hers alone.

She ate fish and chips in her car with the windows down to the cool ocean air. She bought a bag of salt water taffy on the way home, not to eat, but to put on the kitchen table as a memento, like old times. The bright, unselfconscious way it basked in the morning sunshine, and how the pale blue pieces were sometimes the exact shade of the sky on an autumn morning, while the yellow ones mimicked the sun; all this brought a smile to her face almost every time she glanced in its direction.

She would’ve offered Jesse some of the taffy if he had ever come around again, but she never saw or heard from him again. One night while getting ready to watch a movie, Renee picked up the bag and commented on the candy being hard as rocks. Vero paused before saying, “Toss it.”

Vero turned towards the living room as the cabinet door squeaked open. She listened keenly to the nearly simultaneous sounds of the swish of the trash bag and the thunk of the taffy hitting the bottom of the bin. It was not an easy sound to hear, and she reasoned she could fish the bag of candy out of the trash later. She could also drive out to the coast and get more. Of the two options, the drive appealed to her more. There was no rush, though. Whenever Renee had time to go with her, maybe on a dark winter day when the fervent candy could stand in for the sun. It would be an imperfect replacement, but being bright, and hopeful, it would do.

Christopher Williams graduated from San Francisco State University’s Creative Writing program. He currently lives in Oakland, California where he works as a Medical Interpreter. You can find more of his fiction at christopherpaulwilliams.wordpress.com.

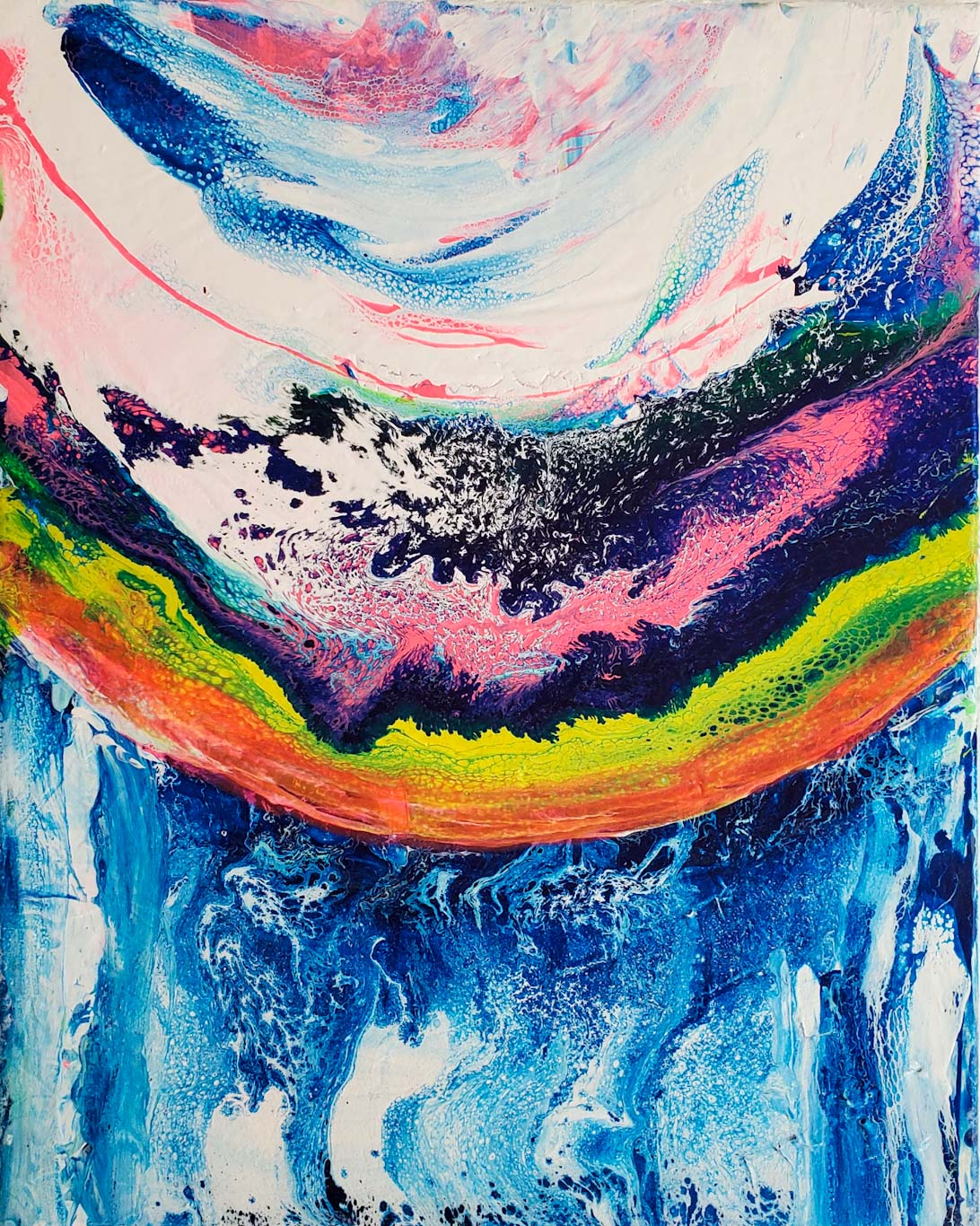

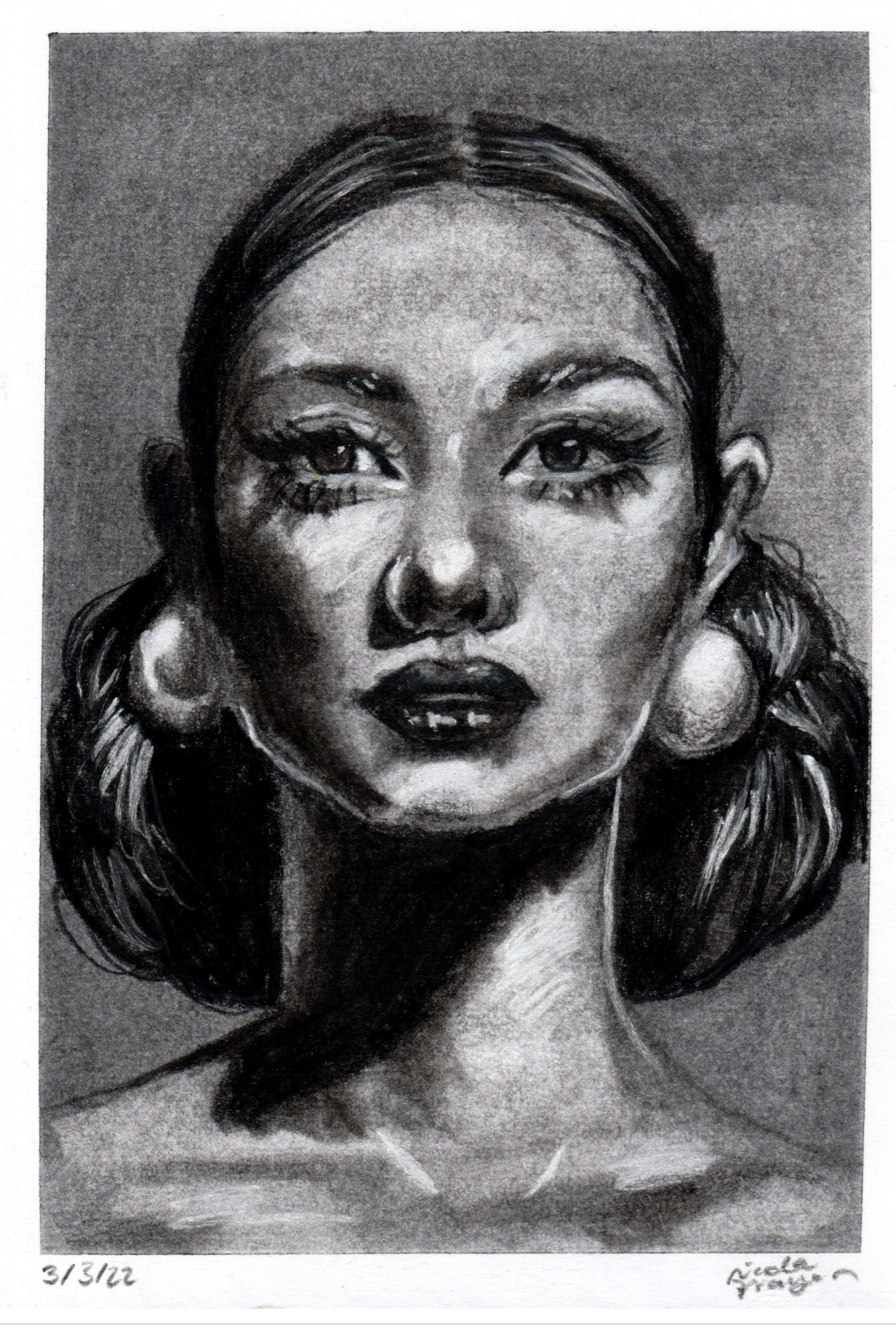

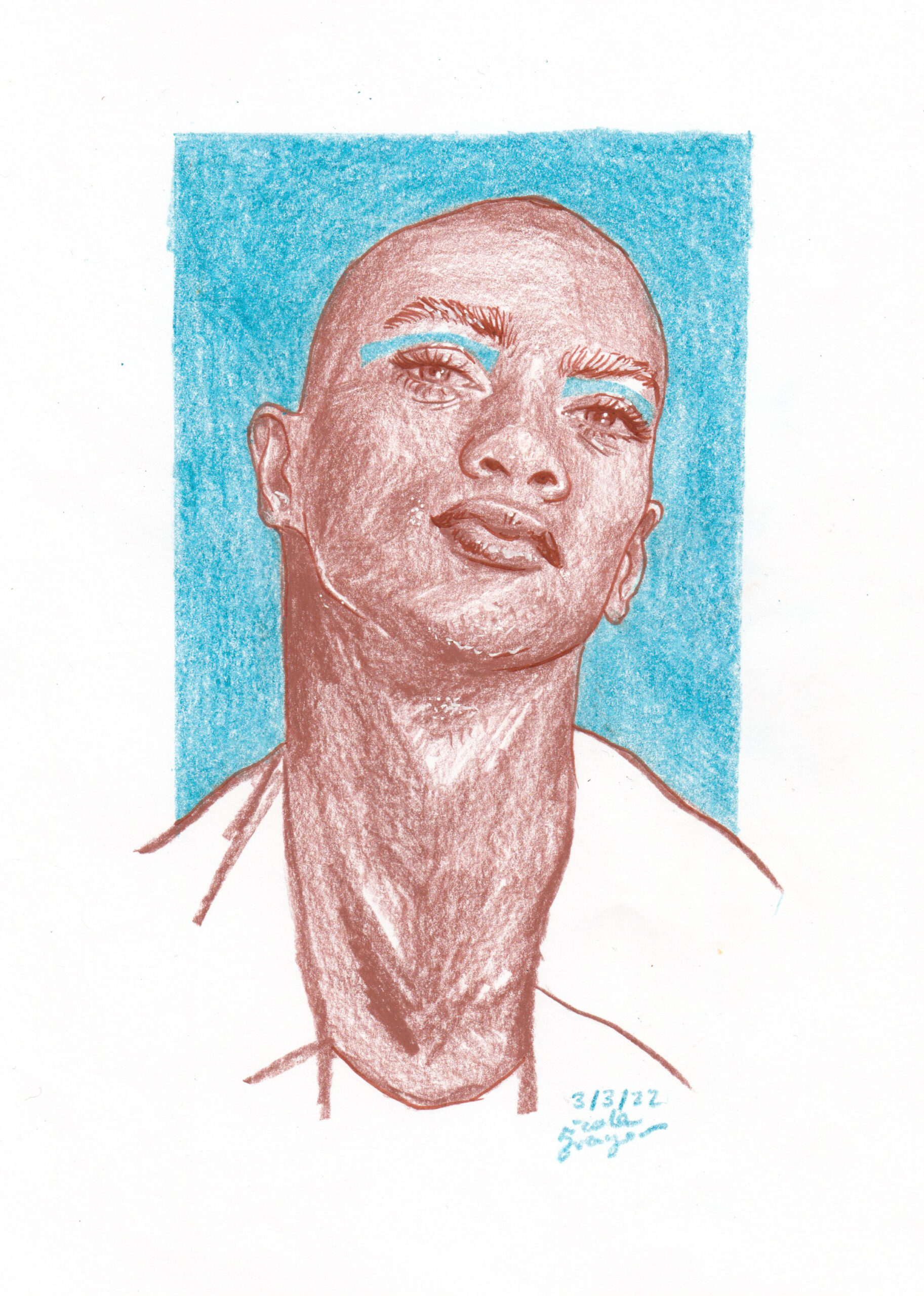

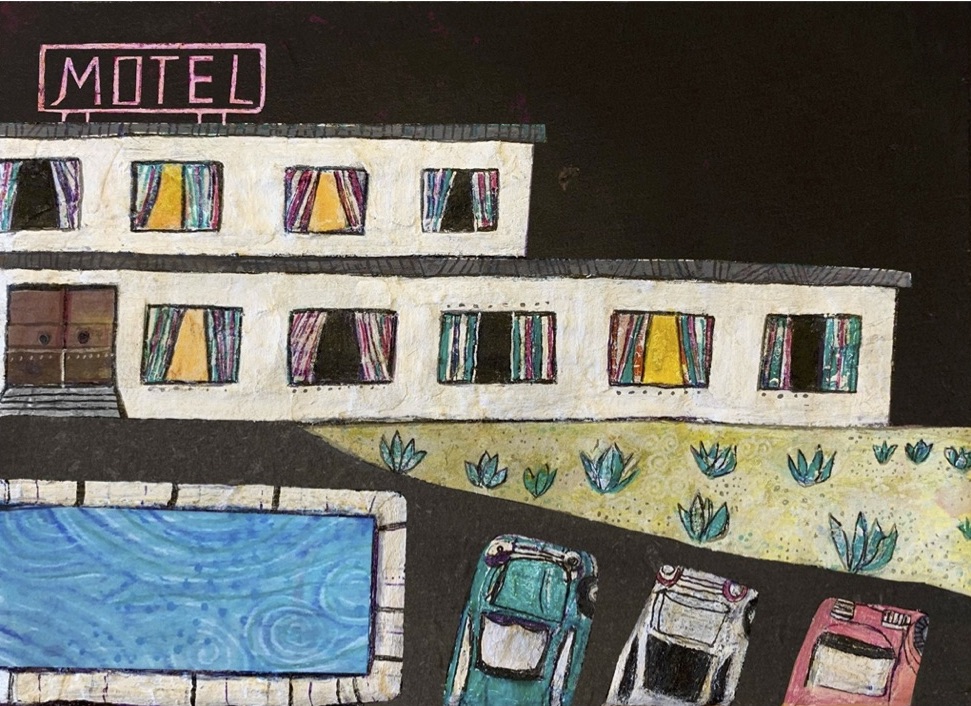

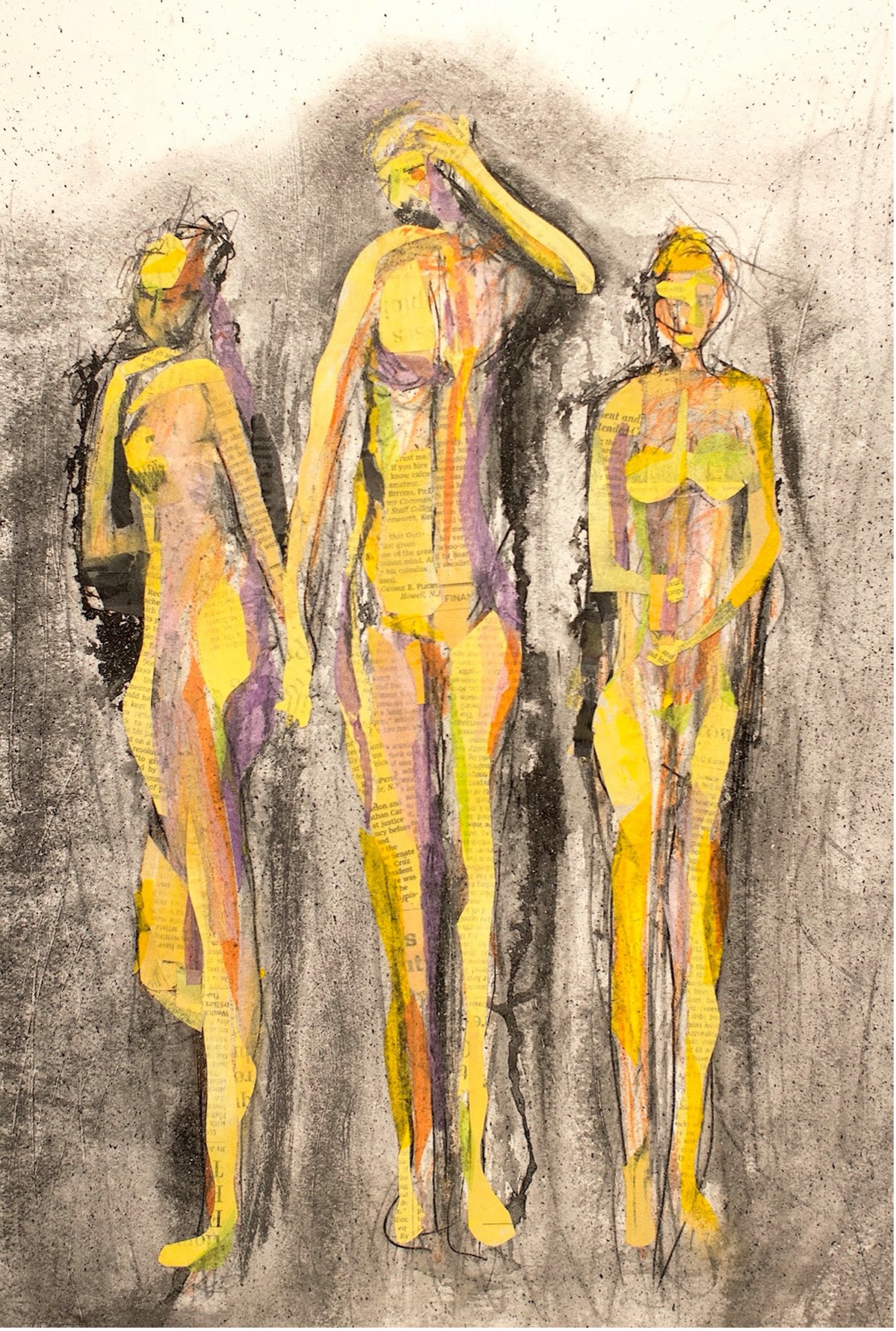

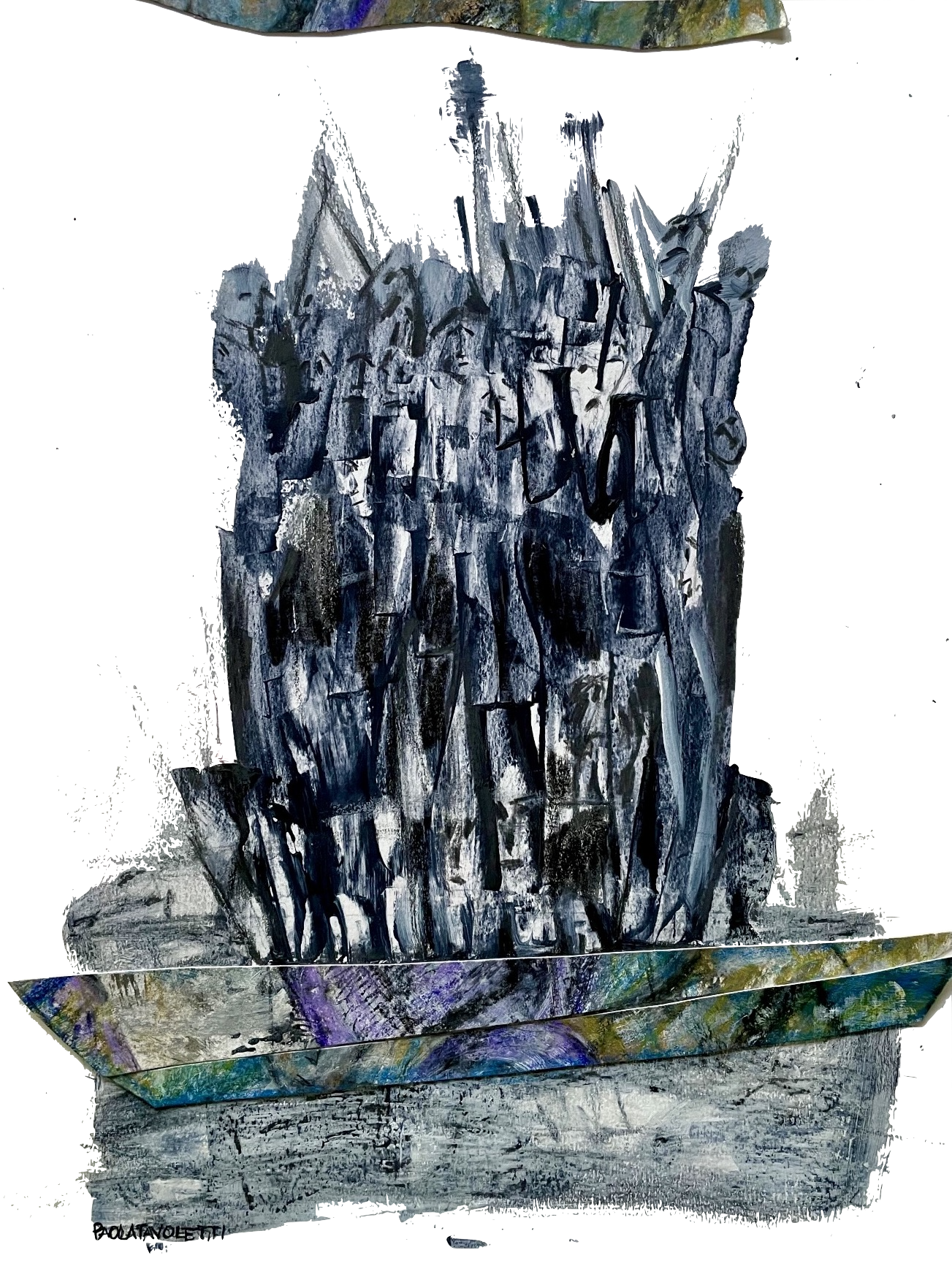

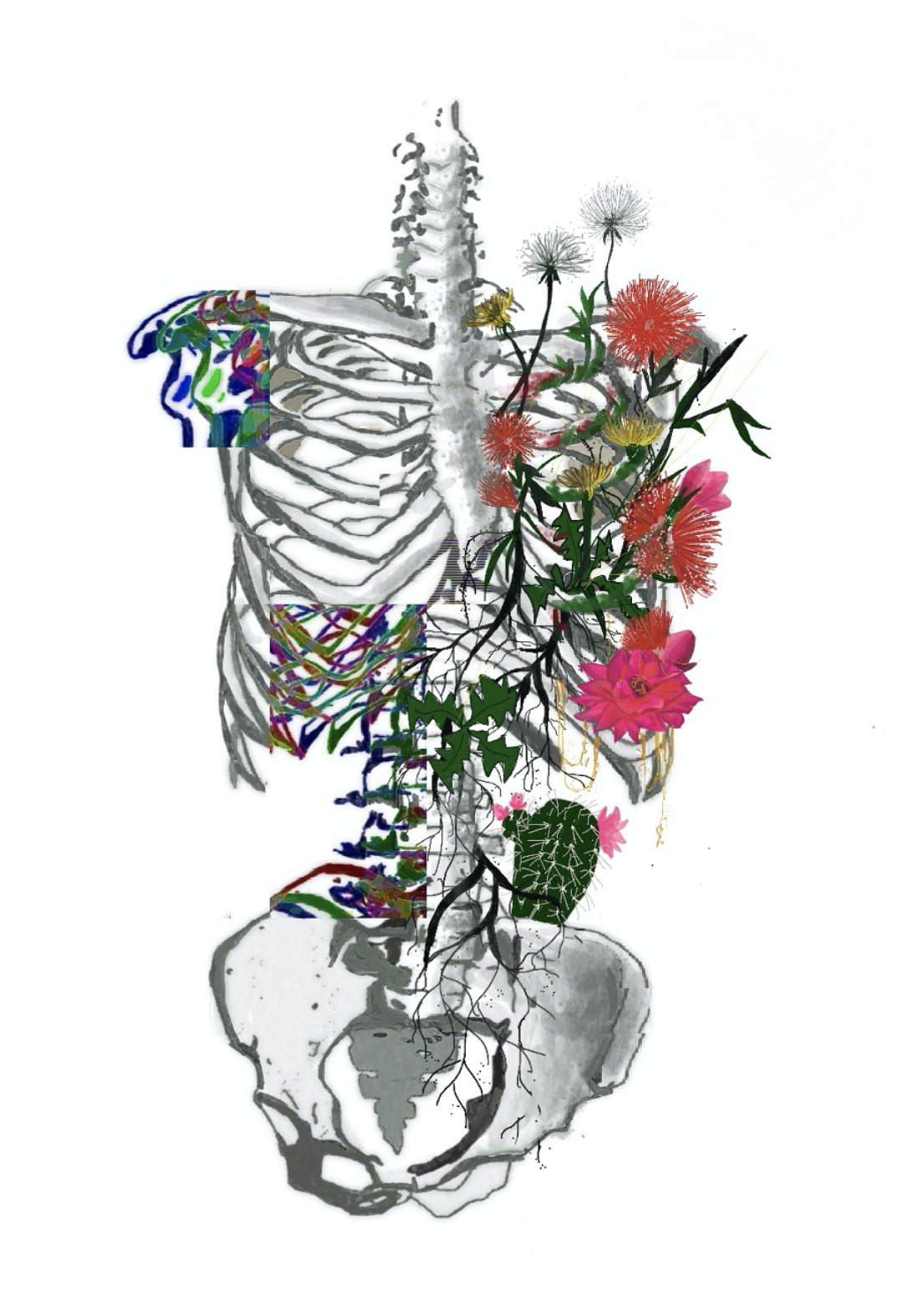

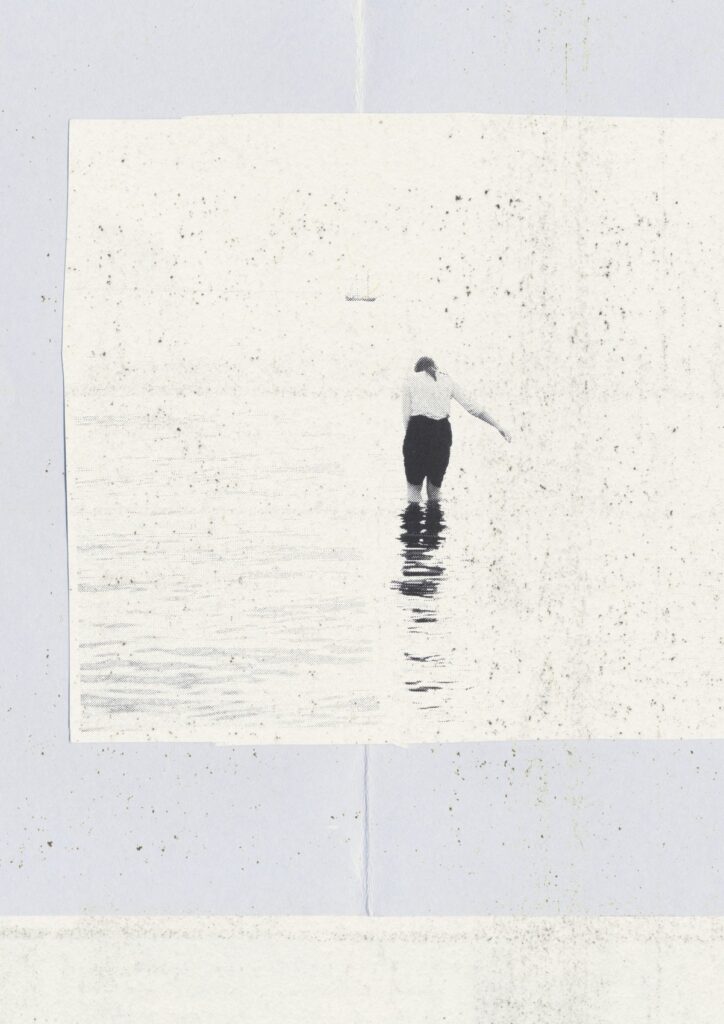

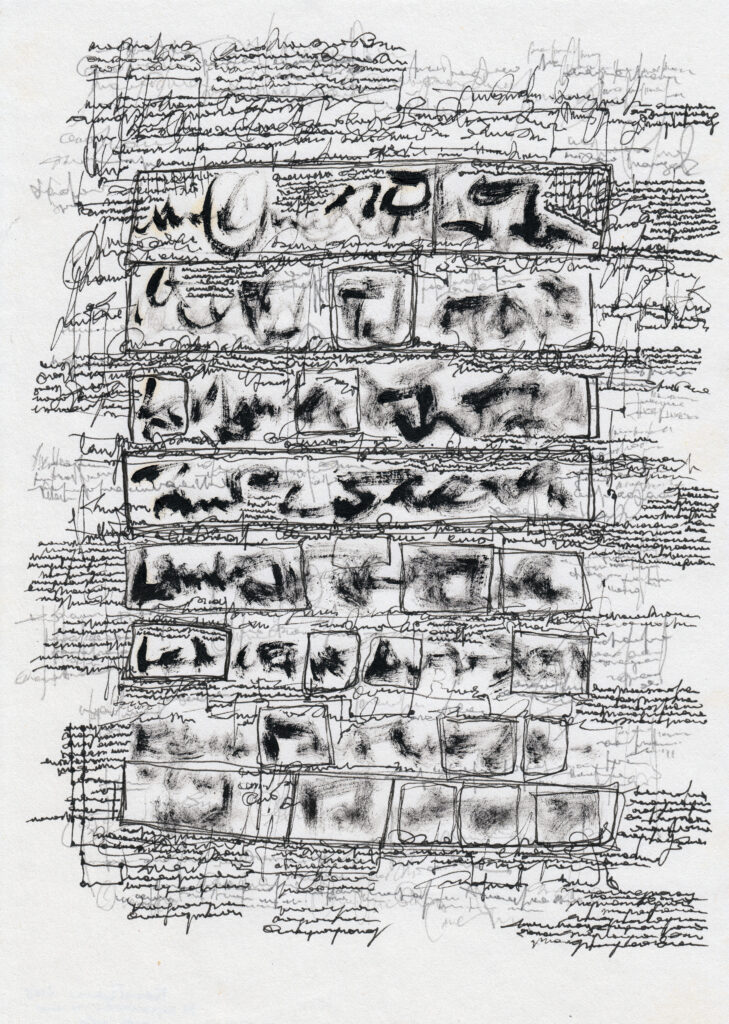

Art: Transitioning by Meghan McGrath who is best known for her large scale, colorful paintings on paper that express the search for memory. The paintings take on a woodblock, print-like appearance with two inch white borders and layering images. Portraits and architectural imagery are juxtaposed to transcend the literal and capture the complexity of memory. Rather than nostalgia, memory serves as a visual history. The portraits become metaphors for maps describing time, place and linear movement. McGrath developed her interest in painting on paper during her graduate years at Colorado State University. For an independent study in printmaking, she made large scale prints of overlapping photos. These works were pivotal to her artistic path, and eventually led her away from working with oil on canvas to acrylic on paper. Born and raised in the suburbs of Chicago, McGrath grew up taking classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. It was there she began to discover self expression through visual arts. She studied art at Northern Arizona University, earning a BFA in Painting and BS in Art Education. She completed her academic education with a MFA from Colorado State University in 2009. McGrath resides in Shorewood, Wisconsin with her husband and two children where she is currently an active artist in her community. She taught art K-12 in Chicago and Milwaukee, and at the College level at Colorado State University. McGrath is collected and exhibited throughout the United States.