The Neighbors

George Lubitz

When I stepped outside to smoke a cigarette, I made sure not to wake Jane. I promised that with the purchase of the house, I would make a conscious effort to quit. A new leaf, if you will. But it was a tough habit to break. To say nothing of the fact that smoking a cigarette in the country was inexplicably more enjoyable than off our balcony in the city, or on the sidewalk somewhere. What’s more—and I don’t mean to harbor on this too much—Jane and I agreed that it could not be a dependency I broke in one fell swoop. And I was in no position to argue. Whenever I did, Jane would deal her signature catchphrase. “Don’t start, Art.” The rhyming had a magical quality to it, like a spell. Once she said that, I was powerless. I knew my leverage was bunk. And so, I made an attempt to cut back significantly and ween myself off. Still, though, I tried to hide my smoke breaks whenever possible.

I stepped onto the deck and lit a smoke before leaning my forearms on the railing and looking out into the property’s surrounding forest. I winced at the cacophony of the crickets and cicadas because I couldn’t hear my own thoughts over their chorus, which defeats almost entirely the purpose of a meditative cigarette, if you ask me. Sometimes I wished I could just press a button and mute the sound of everything but my own breath, blocking out the noises of every little bug that floods the grass. I know it’s not exactly a realistic wish, but a boy can hope. Besides that, though, I preferred the white noise of the country at night to the wallowing sounds of the city any day. Perhaps being able to hear myself think was an overrated experience. I got used to them after a while—their orchestral timbre became as commonplace as wind.

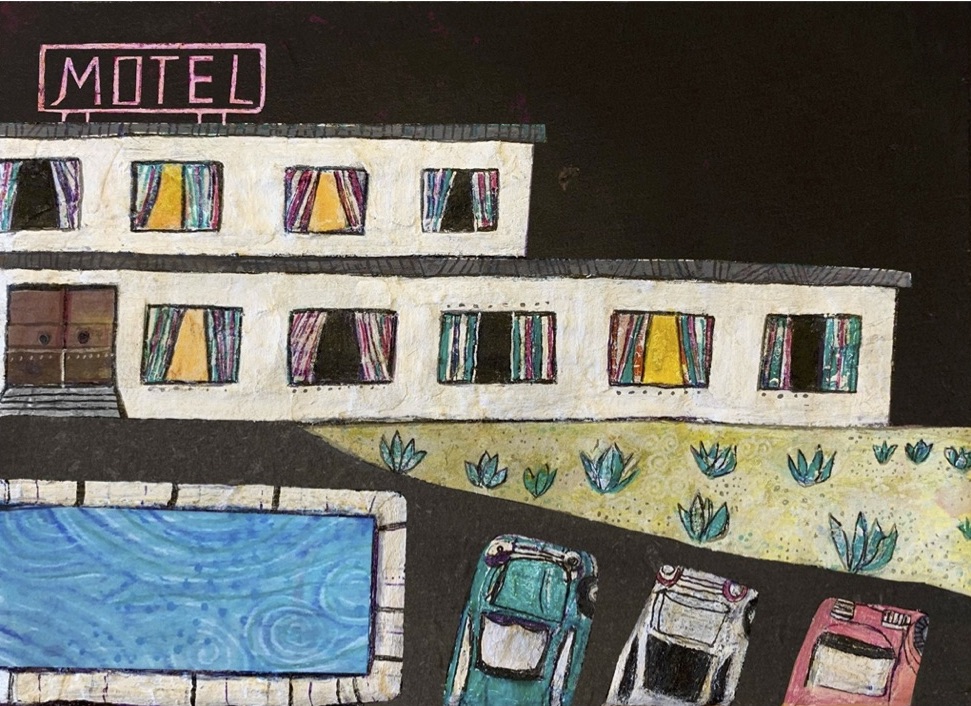

I stepped away from the railing, took a drag, meandered around the wooden deck, and faced the house. The way the lone porch light shone against the all-consuming black of the night air was cute, in a way. The way it stood resolute in its duty to keep on shining, mustering only enough juice to illuminate this small patch of the property. I chuckled at the thought and exhaled a plume of smoke toward it, which was caught in the beams. Out of the corner of my eye I noticed a shimmering neon square. I inspected it from a distance at first, but then moved closer to get a better look. A Post-It fluttered against the calm summer breeze. I plucked it from the side of the house and realized it had been written on. In dark black ink a simple note was typed: I would like to have a peaceful coexistence.

***

Jane and I did not know the property well. What I mean is: this summer was the first time we spent on the South Fork of Long Island. The house—previously owned by a family friend of mine (who I’d met only a handful of times)—was a folly, if you asked Jane. If you asked me, though, it was an opportunity the two of us couldn’t afford to pass up. The soon-to-be previous owner was downsizing to a small retirement community in Moriches and she offered me an excellent price. Plus—and I think this is what finally convinced Jane—the solitude away from the city was just what we wanted. Sure, there was some repair work that had to be done, but it was nothing major. We would only be spending summers and warm-weathered weekends here, anyway. That was the plan, anyway.

After a week of settling in, it started to feel like home. It was a secluded property, exquisitely so. In the back yard, the first order of business was setting up an outdoor woodworking space. Though this adventure into the country was meant to be cathartic, Jane and I had no intentions of completely removing ourselves from our work. We made the necessary arrangements so we could continue our jobs remotely. For my part, I’d worked out a deal with my assistant to help transport furniture down to the city, so that clients could still rely on me to have their commissioned pieces delivered. And my assistant didn’t mind making the hour-and-a-half drive to the South Fork. Perhaps a tad inconvenient, but he was already accustomed to making deliveries within the city, and I’ll add that I paid him well to account for the extra drive time. For Jane’s part, all of her work existed on a laptop, and so the first and only agenda item was installing an internet connection in the new house. Far from it for me to diminish her work, but that was indeed the case. We were both set up shop before we even had groceries in the fridge.

The shopping trip finally completed, and a few maintenance projects under our belts (a new section of perimeter fence, fresh coats of paint in a few rooms), the two of us settled into our new home comfortably. One evening, after having prepared and eaten a simple dinner of roasted chicken and Brussels sprouts, Jane and I took to the back patio, where we sat in folding chairs and shared a bottle of brandy. Not usually what we turn to, but it was a housewarming gift from the family friend, so we decided there was no better time to enjoy it than on this particular evening, when the house finally felt like ours. It carried a decidedly new air that reflected a sense of belonging.

I kicked my feet up on the wooden outdoor table, held out my glass, and proposed a toast to Jane. She turned toward me (her attention was invested in the sunset that creeped below the tree line), located her own glass, and clanked it against mine. I remember thinking: It was one of those beautifully perfect summer sunsets where you didn’t care much whether or not you ever fell in love again, but I didn’t say it aloud.

Instead I said, “I think we’re going to like being here, if only temporarily.”

“You mean, we’re only going to like being here temporarily, or we’re going to enjoy being here, even if it isn’t a permanent living situation?”

I thought to myself a moment, took a sip of brandy, and said: “The latter.”

“I think I can get behind that,” Jane said, and took a small sip herself.

“Amen.” I swatted at a mosquito that landed on my arm. Furtively it had drawn some blood. “I could do without the mosquitoes, though.”

Jane glanced at her own two arms and turned them over to scan for bites. “They never bothered me, actually. I’ve never been bitten by a mosquito, come to think of it.”

“Well, I get bitten enough for the both of us. We’ll have to get more bug spray the next time we go out.” As I said this, I tapped each of my fingernails against their neighboring thumbs, testing their sharpness like a chef deciding on the right knife. I found the length of an index finger’s nail up to par and methodically pressed twice it into a newly formed bug bite, leaving the shape of an “X.”

“X marks the spot,” I said with a smile. I zipped the last of my brandy, like a civil war soldier gearing up for amputation.

Jane laughed. “I remember as a kid, none of my summer camp friends could believe I’d never experienced a mosquito bite. We shared a cabin—maybe six or seven of us—and one morning everyone woke up covered in bites, from head to toe, except for me. Arms, legs, faces bespeckled with red welts. It looked like we’d gone to one of those Chickenpox parties, except I didn’t show. Or maybe that I wasn’t invited. They were shocked, to say the least. I think they were a little resentful, too, because all of them ganged up to make…” Jane trailed off for a moment and sucked on her teeth, thinking critically about what words she wanted to use next, as though it were stuck behind her molars like stubborn particles of food.

She began again: “They built this makeshift…bug box. That’s the only way I can describe it. They took a vinyl sheet from the arts and crafts cabin, wrapped it end-to-end to form a cylinder, and sealed it shut, with an arm-sized door on one end. They wanted me to stick my hand through it after filling the thing with mosquitoes.

“I went along with it because I was concerned with popularity. It was summer camp, after all, and besides, I knew I didn’t have to worry about getting bitten; I was immune from mosquito bites. At least, I was fairly certain. Once they loaded this insect dungeon with scores of mosquitoes, I slid my arm inside and waited. The troop of girls surrounded me as we sat at a picnic table. I was calm about the whole affair, but they were eager to see me get bit. Surely they thought at least one would bite me and leave a mark. But after twenty minutes or so, nothing. They peeled the plastic from around my arm, scattered away from the cloud of buzzing pests that anxiously broke free, and inspected me. Besides the ring left from the entry hole, I was free of marks. That was enough to convince them. From that moment on, I was sure of my immunity. Mosquitoes just didn’t like my blood. Still, though, I wondered what it felt like to be bit by a mosquito. As the girls around the picnic table took turns inspecting my unblemished arm and furiously scratching their own itchy arms, I couldn’t help but feel a little jealous.”

As Jane was telling her tale, I refilled both of our glasses. Once I finished pouring I said, “A little jealous?”

Jane shook her head. “Don’t misunderstand me. I know bug bites are the worst. I mean, they must be. I’ve seen the way people scratch at those things. But I couldn’t help but feel a little passed over, unable to commiserate with the other girls at camp. I felt like a freak of nature. Like their blood was more valuable than mine, just because not even a mosquito wanted to touch me. I remembered thinking, ‘why don’t those mosquitoes want my blood?’ What did they know about me that I didn’t know about myself?’ Maybe it sounds silly to you, but because I didn’t have a place in the ecosystem—because not even the smallest mosquitos saw me in the food chain—I felt insignificant; a non-contributing member of my environment. I know it sounds dramatic, but it’s how I felt. I felt like an alien to my own flesh and blood.”

I took another sip of brandy. “I don’t think that sounds dramatic. One of the most memorable moments of summer camp are the annoying bug bites. It must be a drag to feel left out from that, in a way.” I scratched my arm and re-applied an “X” with my fingernail.

Jane sat forward in her chair. “I don’t think it was simply that I felt left out, like someone who doesn’t get chosen for a game of kickball. There was more to it than that. It was a matter of my place in the world. And of course, I didn’t think in these terms at the time—I was only a child, after all—but I felt saddened at the idea. I was sad I didn’t fit in, like a puzzle piece that is tried in a million different directions but can’t seem to connect to any other.”

I took a moment to mull this over. I’d always known Jane to be a thoughtful person, but this one anecdote struck me. Jane’s story sat between us as though it had pulled up a chair and poured itself a glass. Then I noticed Jane’s brandy glass hadn’t been touched. Her gaze had returned to the trees.

I spoke up: “But even a misshapen puzzle piece finds its place among the others eventually.”

Jane turned her face away from the sunset and smiled. “That’s exactly right.” She leaned forward to grab her brandy glass and took a large swig. She finished her brandy, and I followed suit. The sun was finishing its descent, so we went inside to retire for the night. The weekend had come to a close and, though the fresh change of scenery was relaxing, we would both have to wake up ready to continue with our 9-to-5s.

***

I don’t know what I was expecting to find but as soon as I read the note (and read it again immediately thereafter) I turned around and inspected the small section of the deck before panning my inquisitive stare to the further depths of the backyard, searching for the culprit who’d left the note. Not surprisingly, I saw no one in the darkness. I was searching blind. The insect ensemble came back into focus, but I couldn’t imagine any one of its players had left me this note. I read it again. I would like to have a peaceful coexistence. Just then I flipped the note over, hoping to find more. Nothing. I looked out to the yard again, extinguished my cigarette, and walked back through the sliding door. I nudged Jane and she woke with a start.

“Huh, what?” She gasped.

“We have a visitor.”

She sat up in and turned on the bedside lamp. “Someone’s here? It’s late.”

“No, I don’t mean someone’s here, exactly.” I took the note from my pocket and handed it to her. “I found this stuck to the house.”

Jane read it quickly and flashed me an exasperated look. “What do you mean you found it on the house?”

“I found it stuck to the side of the house, just outside on the deck.” I gestured in the general direction of where I’d found it.

“Don’t start, Art. Are you fucking with me right now?”

“I’m trying to explain, Jane.” I didn’t mean to rhyme, but I didn’t not mean to, either. “I’m dead serious I just found this outside.” I wagged the note in front of her face, at a loss for any more words to convince her.

Jane looked back at it and scratched her forehead, eyebrows raised. “I don’t get it. What does this mean? I’d like to have a peaceful coexistence? Was this from a neighbor or something?”

With a shrug I said, “I don’t know. I don’t think so, anyway. Wouldn’t a neighbor just come up the walkway and introduce themselves in person? Not to mention, we don’t even have any neighbors. No one lives within a mile radius from us. It’s all very weird.”

“No kidding.” Jane’s eyes were fixed on the note, which now lay flat in her lap. “And what is this font? It looks like it came from a typewriter.”

I leaned over to peer at the note. Both of us were hinged over it like coroners over a cadaver. I said, “Hey, you’re right. I guess I didn’t notice that before. So, our suspect owns a typewriter.”

“Well, not necessarily. Maybe they borrowed a friend’s.”

I looked at Jane. “Borrowed a friend’s?”

“It’s possible. Or maybe they’re just very old. I dunno, I just think you’d have to go out of your way to use a typewriter to make this note. So as to avoid detection. Handwriting can be a dead giveaway.”

I considered this for a moment and added: “Doesn’t this worry you? An ominous note like this?”

“Quite the opposite, actually.” Jane shifted in her seat, spun the note back at me like a ninja star, and lay back down before pulling the covers over her shoulders. “It’s reassuring. Any neighbor that wants to coexist peacefully is a good neighbor.” She turned toward the wall and switched off the light. “We can get to the bottom of this in the morning. Shower before you get to bed—you reek of cigarettes.”

After moving about the bedroom looking for a good spot I settled on the mirror above the dresser, right in plain view. The adhesive had lost its stickiness and had to be reinforced by some scotch tape. I stuck it to the mirror, read it for umpteenth time, and headed into the bathroom for a shower. I stopped short of the door leading to the deck and pressed my face against the glass. A soft breeze rolled through the backyard, which I could only hear through an open window. The depths of the yard remained entrenched in darkness, and the stirring of the insects had lulled to a quiet purr.

WHEN MORNING CAME, I immediately turned to face the mirror. Thankfully the note was right where I left it. Unfortunately it also meant I hadn’t simply dreamed up the whole thing. I took a moment to appreciate the stress often offered on by a bad dream, the ephemeral baggage that comes with it, and the catharsis of shedding those made-up concerns like a weary traveler shrugs off a heavy coat. A heady and overwhelming amount of anxiety that dissipates once we rejoin the waking world. But alas, I had this very real note to contend with.

I turned over to Jane’s empty side of the bed. Must already be working, I figured, and rolled toward the dresser. I put on my pants, shirt, and socks while glaring at the note that watched over us as we slept. After I put on my second sock, I took the note from its place, and read it again. I folded the scotch tape over the back and folded it into my pants for safe keeping.

As suspected, Jane was out on the front patio typing away on her laptop. I set two mugs of coffee down on the table and joined her. I sat back in my chair and crossed my legs, folded my hands, and gazed out over the yard. Jane flashed me a smile and returned to her typing. Her keystrokes were fastidious and expedient. I peered over the patio railing and spotted my workbench. I’d forgotten to roll my equipment back into the garage the night before, but figured it was no big deal since it hadn’t rained. Some freshly cut lumber had fallen from a pile but no real damage was done.

“Any clues, detective?” Jane had stopped typing and turned to face me. She took a delicate sip from her coffee mug.

“None yet. Might take a walk around later. See if I can’t find anything definitive.”

“Like bootprints and a receipt from Office Max?”

“If only it were that simple,” I jabbed back.

Jane resumed her typing for a few seconds then stopped for another sip of coffee. A cool breeze rolled through the yard and brushed up over the railing to meet us. It was the type of midsummers breeze that reminded you what fall felt like, if only for a moment. She spoke up again: “The water here is very hard. Ruined my hair; makes the coffee taste different.”

“Good different or bad different?” I said.

“Just not as good.” She took another sip and winced. “I mean, it’s just something I noticed, is all.”

“You think the water is better?”“I do. I really miss it. What I wouldn’t do for a sip of city water.”

“Maybe we can have my assistant bring a couple jugs next time he comes out.”

“That’s not half bad an idea.”

“Still, though,” I began, “Look at all the trees and smell all the air. Take a look around. I don’t know about you, but some off-tasting water is a pretty good trade for serenity like this.” I swatted at a fly that was buzzing around my head.

“Just like summer camp,” Jane said.

“I know you prefer the city, but didn’t we both agree that some time away would be nice?”

“You’re right,” she said with a sigh. “I like the country. I like the trees and the air does smell crisper than the musk of the city. But…” She turned in her chair to face me completely. “I don’t think I like it as much as you do.” As she said that, I noticed Jane’s outfit for the first time. An oversized bright pink v-neck blouse, skinny black jeans, and a pair of all-white thick-soled sneakers, her jet-black hair done up in a bun. She was a fashion designer by trade, and her getup clashed with the simple country backdrop.

“How do you mean?” I said.

“I mean…” She trailed off and peered into her empty coffee cup. “I mean, I think you have nostalgia for something you’ve never known.”

“Something I’ve never known?” I looked around, as if to find an answer in the trees. “What is that?”

“I mean the country, is all. I’m not trying to be mean or anything. We’re both from the city; we’re both born-and-bred New Yorkers, but I think you have a yearning to get back to the country, even though you’ve never known it. You have an affinity for something you haven’t ever experienced. When was the last time you spent time in the country? Inundated by all this?” She held her arms out to balance the trees on them, like how a waiter carries heavy plates of food.

I sat back in my chair. “Well, I don’t know that I ever have. You’re right about that, but I disagree that I’m trying to return to nature in the way you’re suggesting.” I used air-quotes to say return to nature.

Jane put a hand on mine. “I’m not suggesting you’re making a pilgrimage to Long Island, Art. I mean, I’m not saying that. I’m just saying you take a greater stock in being out here and it’s uncharacteristic for you. Don’t get me wrong—I like being here, too, even if the water is harder than I’m used to. But I know we both feel a little out of place. It’s not where we belong, even if it is a nice break from the quotidian routine we have in Brooklyn. Don’t you feel a bit out of sorts? Don’t the bugs bother you? The constant symphony of cicadas? I don’t want this to be permanent, is all I’m trying to drive at. I don’t think I could handle it.”

I folded my arms and chuckled. “Who says it’s going to be permanent? You think I’m going to lay my roots down here and stay planted forever?”

Jane picked up her coffee cup and heaved it up toward her mouth to shake the last few drops free. Then she took my coffee and stole a sip. “No, no. I don’t think that. I don’t know what I think. Maybe I just miss the city. I’ll probably get more acclimated in a few days. Maybe our new friend will help make me settle in.”

“Our new friend? You mean whoever left the note?”

“They seem friendly enough, after all.”

I pulled the note from my pocket and unfolded it before laying it flat on the space between us. “What do you think a peaceful coexistence even looks like?”

Jane picked it up. “It’s hard to say. I suppose it depends on who you ask. If it were up to me, a peaceful arrangement might include no loud music late at night. Perhaps a borrowed cup of sugar when we’ve run out.”

I nodded. “I’m going to get to work. I’ve kept you from yours long enough.” I kissed Jane on the head, stole my coffee back, and walked down the patio stairs toward my workbench, which is where I found the second note.

IT WAS THE SAME shade of neon yellow, with the same font; typewritten ink that driven to the page by an assault of chopping metal arms. What’s more, it looked fresh. Not the least bit crumpled and without any wear, as if it materialized from out of thin air. I almost tripped over my two-by-fours and quickly plucked the note from its resting place on the side of my workbench. I’m so sorry to have borrowed this. I borrowed it to complete a project. I hope you didn’t find any trouble without it. Like before, I read it again and again. I jumped over the pile of lumber and rushed back up the patio stairs to show Jane.

“We got another one,” I said, short of breath.

Jane pushed her computer away and stood up. She took the note from me. “I’m so sorry to have borrowed this. I borrowed it to complete a project. I hope you didn’t find any trouble without it.” A stray lock of hair danced in front of Jane’s nose and she quickly tucked it behind her right ear. “What did they take?”

“I’m not sure.” I said. “It was left on my workbench, but I can’t imagine they moved the whole thing without us noticing.” I crossed my arms and looked at Jane like an exasperated parent might at a petulant child.

“Did you notice anything missing?”

“I have no idea. I left my tools out. But I didn’t stick around to do inventory. I saw this note and rushed up here.”

Jane sat back down and blew a thin steam of air through pursed lips. “This is getting kind of creepy.”

I said, “You think? I think we should call the cops.”

Jane looked up at me and furrowed her brows. “That’s a terrible idea. They aren’t going to do anything. You think they’re going to bother themselves with a rogue note-leaver? Plus, as far as the law is concerned, they haven’t done anything, except for maybe trespassing.”

“That’s exactly right—trespassing. Someone’s been coming onto our property.”

Jane put down the note and held up her hand. “Maybe so, but we can’t persecute a trespasser if we can’t even locate them.”

I sat down, my mouth agape. “What are you talking about? This doesn’t freak you out? Some random person coming into our yard and leaving threatening notes?”

She laughed. “It’s a little odd, to be sure. But it isn’t threatening. I don’t feel threatened, do you?”

“Yes, of course I do. Why don’t you?” I clasped two hands together and rested them on my head.

Jane closed her laptop. “They borrowed one of your power tools, Art. And they were very nice about it, if you ask me.”

Like one of those dreams where you try to speak but none of the words will come, I stared at Jane, unable to pick the ones that would resonate with her.

She spoke up again: “If you really want to know, I think you’re blowing this whole thing out of proportion. Yes, it’s weird. Yes, it’s unorthodox, but we’re guests here. We’re transplants from another world. Maybe this is how neighbors communicate around here. Maybe they’re too shy to meet us face-to-face. Maybe you yourself give off a threatening vibe. Hell, maybe I do, too. Maybe the locals are trying to keep a safe distance and feel us out.”

I squeezed the bridge of my nose in a cartoonishly exaggerated manner and said, “Do you think the locals are martians? That they have to leave us sticky notes to get a message across?”

Jane smiled softly. “Well, we’re the aliens in this scenario. More like an invasive species. Not to sound too dramatic or anything, but that’s how I see it. No man is an island, you know. It’s a nice sign that our neighbors have made something of a peace offering by leaving these notes.”

I laughed. “Usually a peace offering involves giving something over, not taking something away.”

Jane smiled again and folded her arms. She looked off to the tree line, as she was wont to do, and closed her eyes to let her face bask in the sunlight. Facing away from me, she said: “It’s just like with the mosquitoes.”

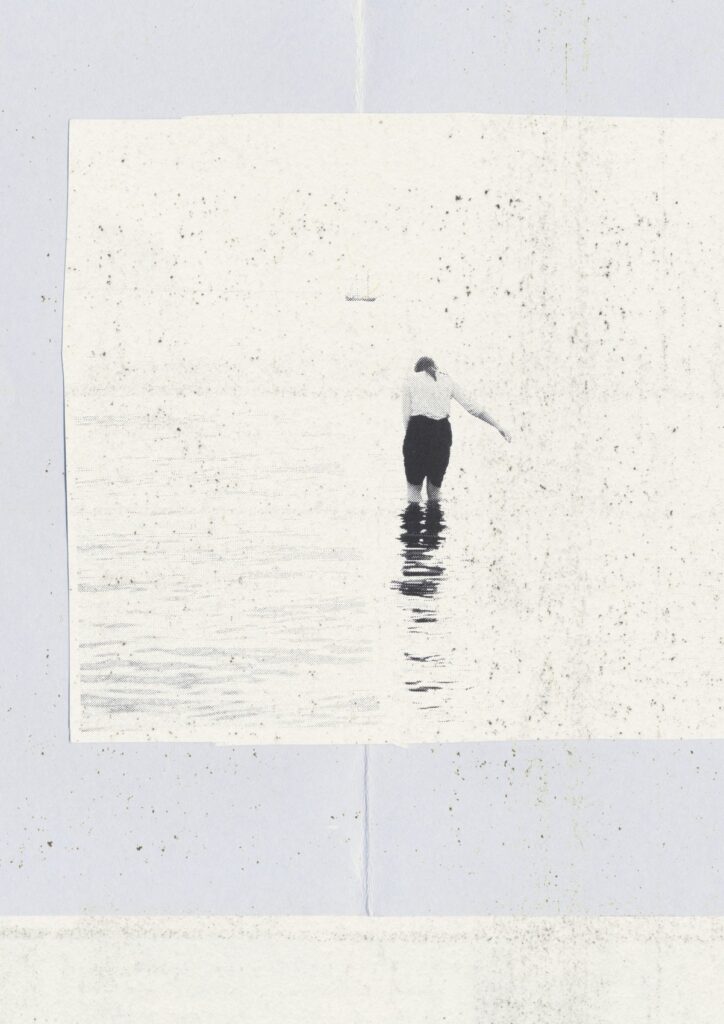

Suddenly, it dawned on me that Jane looked different from when I had last seen her just ten minutes prior. Not exactly her physical looks, but her demeanor. The patio was her chrysalis and she had undergone a sort of metamorphosis, but only of her aura. I don’t know why or how, but it seemed to me that within moments, her outlook and attitude had shifted dramatically, yet she appeared more or less the same. Perhaps it was a slow process that began when we first moved into the house. An altogether overwhelming change of place that overwhelmed her. That much I couldn’t say, but I thought better than to engage with her train of thought. It’s just like with the mosquitoes, I repeated internally. I got up without a word, took the note from where it lay on the table, and walked back downstairs. But instead of working, I decided to take a walk. As I started into the trees, I looked back at Jane, sitting up on the deck. Her figure was backlit by the sun and it gave her a commanding presence behind the laptop. The whir of cicadas grew and, for one reason or another, I thought to myself, No man is an island, but some women are.

I LIT A CIGARETTE and sauntered through the front and back yards, which gave me quite a bit of territory to cover. I wasn’t exactly sure what I was looking for, but I figured it wouldn’t hurt to sleuth for clues. Plus, I was still pretty rattled from the second note and could use the time to settle my nerves. I thought about what Jane said as I made my way around the perimeter, stepping over twigs and ducking under pine branches. I thought about the pesky mosquitoes that had taken a liking to me as I walked, and how undeterred they were in their quest despite my repeated swats. It’s just like with the mosquitoes, she had said. How exactly, I hadn’t yet pieced together.

In the corner of the front yard lay a clearing composed of felled brush. By the looks of it, it had been trampled on frequently, yet no discernible prints pointed to any one perpetrator. Long stalks of overgrown grass had fused to the dirt and what was left was a stopgap trail leading deeper into the woods. So naturally, I followed it. I took another drag of my cigarette and exhaled through my nostrils. After a few more steps forward I stopped and peered over my shoulder. The final frame of my backyard and house loomed stilly just beyond the green foreground. I faced forward and continued deeper into the woods. Suddenly, I was struck by a rather silly thought that the dense undergrowth would spring back to life and block off the trail. That the verdant corridor would collapse and expand to trap me. I laughed at the thought and continued on.

Before long I noticed I’d smoked my cigarette all the way down to the filter. The lavender-colored smoke danced into view, so I let the butt fall to the forest floor. Just then, I heard a rustling and stopped in my tracks. I stood up straight and scanned the branches for movement. I spun around on my heels but kept otherwise still, listening for the faintest snap of a twig. Silence. I inched forward in a crouch. I moved guardedly along the path until, suddenly, another rustling of branches came from my left. I could only see a few yards through trees and couldn’t locate who or what was rustling. It grew louder (and closer still). Eventually, the rustling turned to footsteps, the cadence of which sounded like a tight, graceful gallup. It grew nearer and nearer until I stood face-to-face with the noisemaker—a large buck leaped over the blur of flora and landed right in my path.

“Would you please put out that cigarette? I don’t want it starting a fire, if you don’t mind.”

All the blood in my body flowed into my head. Specifically, my ears began to grow hot and itchy. Like a tidal wave reaching an unsuspecting shoreline, the sound of frenzied cicadas rushed into my ears and drowned out all else. I stared at the deer. He was huge, at least three times my size. His looming white antlers looked like a Kindergartner’s rendition of an autumn tree, free-flowing and thick, with no consideration for direction or space.

“Sorry if I startled you. I don’t mean to be a bother, but I don’t want my home burning to a crisp. I’m a bit sensitive about that.”

I tilted my head down and—in slow-motion—scanned the forest floor for my cigarette butt. The thin trail of smoke led me to it and I stomped it out. My leg felt heavy like iron.

“Thank you. I really do appreciate it.” The deer spoke again, in a deep but soft tenor.

I tried to speak but the words simply wouldn’t arrive. They didn’t make it past my belly, much less my throat. Even if they did, I wasn’t even sure what the words would be, nor would I know what order to arrange them in.

The deer lowered his gigantic head to eye-level, almost as though bowing. I looked into his dark eyes. He spoke: “I really don’t mean to cause any concern. I’m sorry to have jumped out at you like this, and I’m sorry about the notes. I didn’t know how else to make my presence known.”

Finally, I found the words, but my shaping of them left much to be desired. “Th-the notes? Y-you left those?”

“Yes, it was me. I trust they didn’t cause too much alarm? If they did, I’m very sorry.”

“How…” I trailed off and the chorus of forest bugs rushed back into my ears. I shook my head and focused. “How did you…how do you know how to speak?”

Without missing a beat, the deer said, “The same way you learned, I might imagine. From constant repetition and practice.”

I didn’t respond. My heartbeat replaced the cacophony of bug sounds. Or rather, it harmonized with them.

The deer continued: “I realize this might be hard to believe, but the woman who lived in your house before you terrorized me and my family. When I was young, she would shoot at us with BB guns and chase us through the yard. Naturally, we were much faster than she was, but she was relentless.

“But you see, a large fire had destroyed our home a long time ago, before even the woman lived in your house. Acres and acres were depleted in a matter of weeks. I’m not sure how it started, but it forced all creatures—my family and countless others—to move inland, closer to humans. It’s not ideal, sure, but we have no other choice. That’s why I left you the note. I wanted to make sure we got off on the right foot.”

My heart rate slowed and the sound of my heartbeat made its way out of my ears. I repeated what the deer said back to me. It was the first time I internalized the sound of an animal. “You wanted to coexist peacefully? Because you couldn’t find that with the woman who lived here before me?”

“Precisely. Did you know her? Personally, I mean.”

I told the deer that I did, but she was only a family friend. We weren’t exactly close.

The deer nodded his large face. “I understand. She was not kind.”

“I’m sorry about that,” I began, “but you don’t have to worry about Jane and me.”

“That’s very reassuring. Thank you.”

“My wife Jane,” I began, but thought carefully about how to continue. “She had a theory that you were apprehensive because we were an invasive species. That we didn’t belong here—aliens was the word she used. She said that the locals here must behave that way. I suppose she was right, in some way.”

“I guess we’re both alien in our own ways,” the deer said. “You and your wife just moved into the house, but my family and me are still recovering the destruction of our old home, even if that fire went out years ago. Your backyard is still foreign to us, and we come across other animals that we wouldn’t normally intersect with. To put it another way, we’re constantly stuck in traffic, and it’s a gridlock we must learn to grow accustomed to.”

“Do you mind if I smoke another cigarette, if I promise to put it under my shoe?”

“That would be fine—certainly.”

I pulled a cigarette from its pack and lit it between my lips. After an exhale, I said, “I don’t suppose you’d like one?”

“No, thank you; I don’t smoke.”

“Of course not,” I said, and laughed. “That would be ridiculous.” I took a long drag of my cigarette and inhaled deeply. Out of habit, I turned away from the deer (Do deer dislike cigarette smoke?) to exhale. I was struck suddenly by a question I had to ask: “I’ve got to ask—What did you take from my workbench? Your second note said you borrowed something, but you didn’t say what.”

“Sorry for not being clear. I tried to place the note carefully but I didn’t want to knock over any of your tools and startle you. I borrowed your…well I don’t know what you call it, but it’s the device that help keeps the mosquitoes away.”

I thought to myself for a moment. “Oh, you mean my citronella diffuser. It works wonders. I hope it worked for you.”

“Yes, indeed,” the deer said. “I noticed you switching it on while you work outside. Regrettably, when the bugs flee from you, my family and I become their new target.”

“You watch me working? Seems a little sinister, if you ask me.”

If deers could shrug, this is what this deer did, by lowering his head and keeping his shoulders firmly in place. “Call it whatever you like. But, like I said, I had to scope you out and make sure we could live symbiotically.”

I smiled, and for the first time, let my guard down, although whatever guard I did have would surely be no match for this polite beast. “I’m happy to live in symbiosis with you and your family. No man, nor deer, is an island.”

“No man, nor deer is an island.” The Deer repeated the phrase back to me, as though he were trying to find the words himself. “As I said before, this is really reassuring to hear. I look forward to it.”

“Believe me, I feel better about the whole thing, too. I was worried some creepy human was going to…Well, I don’t know what I thought.”

“I’ll make sure not to leave any unnerving notes any longer, now that we can just speak like neighbors.”

I nodded and began to make my exit. “I have one more question.”

“I’m all ears.”

“Why the font? I mean, why did you write the notes with what looked like a typewriter?”

“This may sound overly simple, but I don’t know how to use a pencil.”

“And so you used a typewriter because it’s easier?”

“Precisely. I borrowed it from a friend.” The Deer shook his head to knock loose some mosquitoes and fleas, and wandered back into the brush.

I made my way back out from the woods and into our property. Jane was no longer working on her computer, and through the kitchen window I could see her washing some dishes. I had no idea how I’d tell her about my findings, but somehow I knew she’d be receptive.

I could sense rain was about to fall. Swirling clouds took up the better part of the sky above. I rushed to pull my workbench, wood, and other materials into the garage to keep dry. Once done, I closed the door and let myself inside the house through the garage. As I made my way up the stairs, I wondered if we had an extra cup of sugar lying around, in case our neighbors had run out.

George Lubitz is a writer based in his native New York City. He attended Skidmore College, where he received a BA in Creative Writing. His stories have been published in Tempered Runes Press, Pif, and The Adroit Journal, among others. When he’s not writing, he enjoys taking photos on film, which can be viewed on his Instagram, @razz.p.berry. His website is georgelubitz.com.