The Drain

Heather Lynne Sparks

I sat up groggily, the bruising, bursting soreness of my overfull chest aching as I reached for baby Jack in the darkness. But he was still in a deep sleep.

The light from the missed call blinked, and I realized it had been my phone vibrating. I reached for it on the nightstand. 1:47am. My mom.

I tapped the screen to call back, and the brightness hurt.

She picked up before the first ring. “Heather. Hello? There’s been an accident. It’s Megan. Megan got hit on her way home.” I could hear traffic in the background as she drove. “You need to get to the hospital. St. Joe’s. We’re on the way.”

She kept talking as I woke up. Jack stirred in the bassinet. Jesse was awake, fumbling for his glasses. Mom’s breath caught in the receiver. “Heather. You can see the wreck on the freeway.” There was a quarter of a mile pause as she drove. “They’ve shut down the other side.”

I felt around on the floor for a flannel shirt to pull over my nursing bra and tugged on a pair of reluctant stretchy jeans, my soft stomach resenting the buttoning of actual pants.

Jesse was sitting up in bed now. There’s an ounce and a half of milk in the fridge, I said, recalling the 45 long minutes it had taken to pry the liquid from my begrudging body. Jack was due to eat in another hour. There was formula in the pantry. I didn’t know how long this would be.

He handed me my keys. “Ok. Ok, ok. Go.”

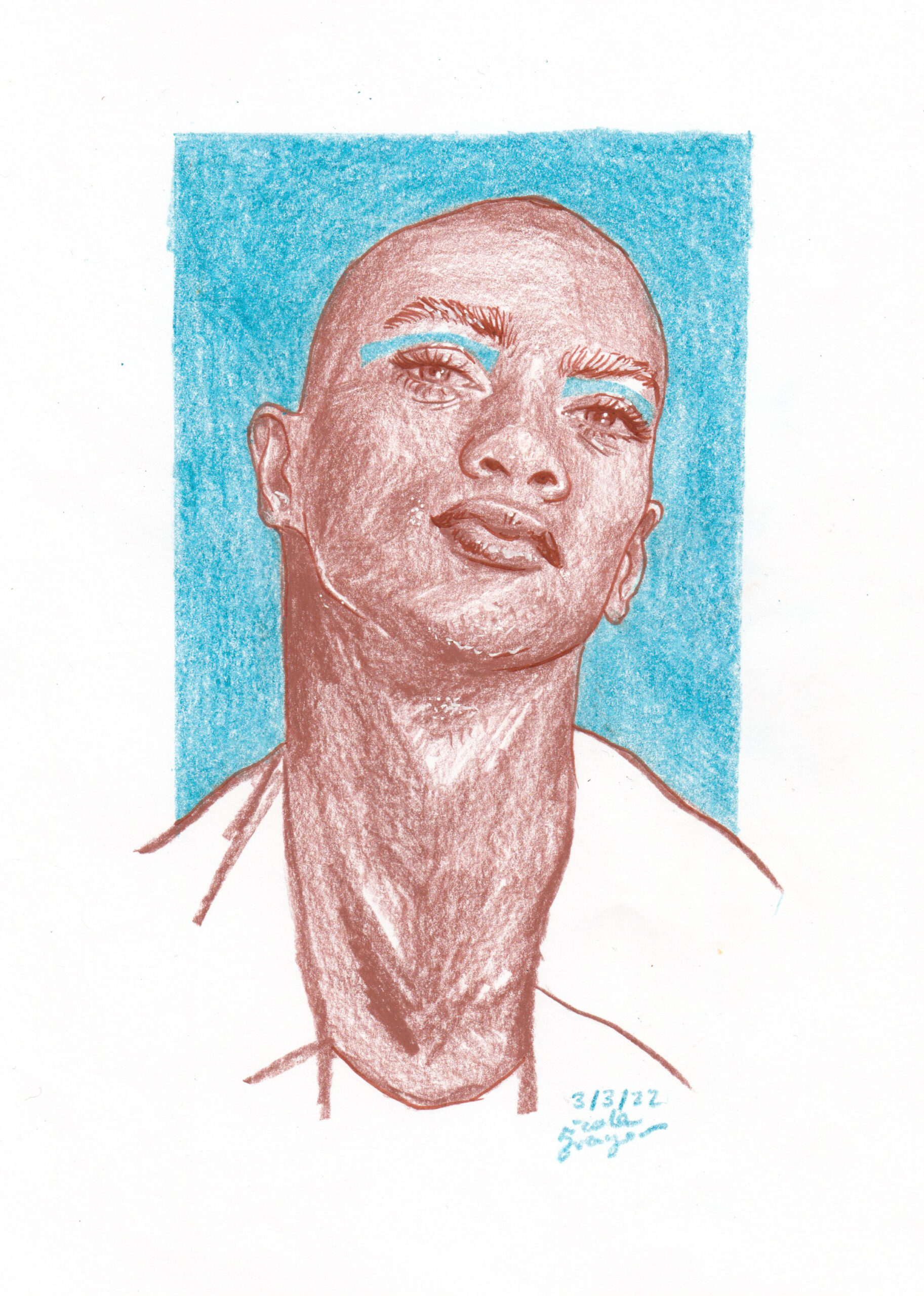

My sister-in-law worked as a 911 dispatcher for the fire department. At twenty-six, she’d been there for a few years and was still the youngest team member — though you wouldn’t know it from the canvas tote bag filled with knitting needles and aspirin she kept at her station. Still low on the department totem pole, she’d been assigned the graveyard shift. Normally, she didn’t get off until 7am, but she’d been surplussed that night and had been headed home early to my brother and their two boys. Sean was two and Miles was six months.

Calling her my in-law never seemed adequate. I’d have claimed Megan, with or without her marrying my brother.

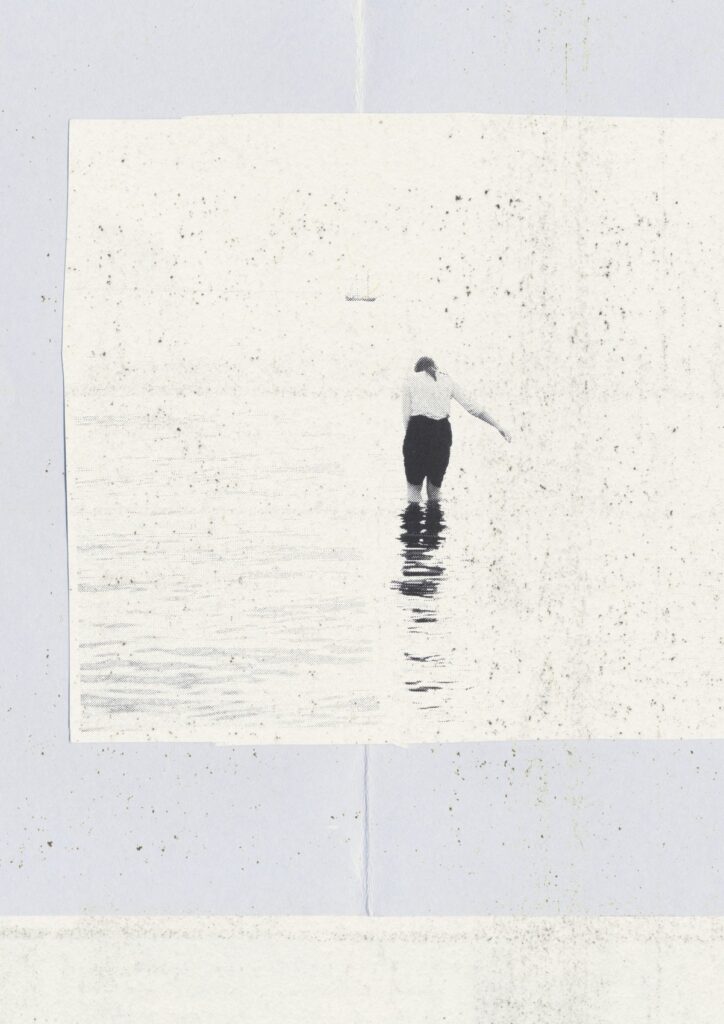

January is always unexpectedly cold in Phoenix, and I fumbled to remember where the Prius’s defroster button hid. The regional dispatch center was just shy of an hour’s drive south from the suburbs my family lived in, and Megan commuted the same way every other suburbanite did: the city’s central vein, the I-17. St. Joseph’s Hospital was an old hospital — it had been an old hospital when I was born there in the 80’s. It wasn’t far from Megan’s work, but it also wasn’t the closest hospital to her work. It was, I thought, the closest Level I trauma center. I kept the radio off.

I drove south in silence, floating through the nearly-deserted artery of 18-wheelers and late-night commuters. My chest throbbed; I should have brought the breast pump. I was close to my exit when I saw distant sirens strobing on the other side of the concrete barrier. I lifted my foot from the gas, coasting as slow as I dared past one, two, four — eight? sets of lights pulsing against the dark. Then, broken sections of metal remains — her burgundy Kia mixed with a Chevy SUV, everything facing in the wrong ways. Uniformed men walked the interstate under yellow streetlights, moving slower now that the ambulances had left. It struck me then that my brother had been in the car when Mom called.

The city gets seedier the further south you head on the 17. Getting off on Thomas Road had me checking my door locks at the stoplight. I scanned the hospital’s signage for the E.R. and pulled into the lot. It’s easy to find parking at 2:30 am.

Our family, all sweatshirts and pajama bottoms, huddled outside of the emergency triage — a tiled corridor of beds separated by pale blue curtains. Several firefighters and dispatchers stood off to the side. When you answer for 911, sometimes you answer for people you know. Sometimes you answer a call about your coworker ten minutes after she left.

“Where is she?”

Getting prepped for surgery. She’ll be wheeled out soon.

“Where are the boys?” I meant Megan and Patrick’s boys, not mine.

At home, sleeping. A cousin was with them.

I couldn’t find Patrick. “Where is he?”

In the parking lot, with Uncle Jimmy.

Uncle Jimmy is not the one you go to when you are sad or scared or even when you need to translate medical jargon. Uncle Jim is the family muscle. “Wait — why?”

No one answers at first. Eyes drift to a second triage curtain concealing the source of loud and slurred sobbing. Loud and slurred and conscious sobbing.The Chevy driver.

Uncle Jimmy is out in the parking lot, restraining my brother.

I hadn’t thought about the other driver yet. And I didn’t know. I didn’t know that when you’re taken to the hospital after a drunk driver hits you going 70 miles per hour south on a northbound highway, his ambulance will drive to the same hospital and he will be sitting up, one faded blue curtain away from your fading body.

It seemed like a gross oversight, either on God’s part or the hospital’s.

I’m the middle child of three. Older sister, younger brother, and me. Patrick is three years younger than me, but he’s been bigger since I was 11. He’d race me home from school, win, and beat me to the TV, where he’d sit on my back, pinning me to the floor so that he’d have control of the remote. If I tried to change his Power Rangers back to reruns of Full House, he’d pull my hair and laugh.

When I had my first middle school break up, a traumatizing crucible in which my 12-year old boyfriend told the entire seventh grade that I was both a prude and a slut, my fourth grade baby brother had my back in a different way. He chased Dustin Marley across the playground, through the kickball field, and off campus. The whole school watched.

Patrick came back through St. Joe’s automatic doors with wild eyes. Megan’s gurney rolled out for surgery; she was trached and vented. We were able to touch her hands and tell her body that we’d see her soon. That we loved her. Patrick whispered something into her ear, kissed her temple, and then walked himself to the bathroom.

Our growing group moved to the ICU. Megan’s parents were there now, and her grandparents, and more cousins. Her bishop. The quiet talking resumed. The operation would put a shunt in her brain to relieve swelling. Neck injury. Carotid artery. Stroke. Hemorrhaging. Her little sister was driving down from college. My dad was flying in from business in Atlanta. The bishop wanted us to hold hands and pray.

Each time someone new walked in, there were long hugs. I was swollen and sore against my maternity bra, and each squeeze brought physical pain. I thought of the measly ounce and a half of refrigerated breastmilk I’d left, 40 minutes away at home with a hungry-by-now baby Jack and cringed. But this was not important here, now.

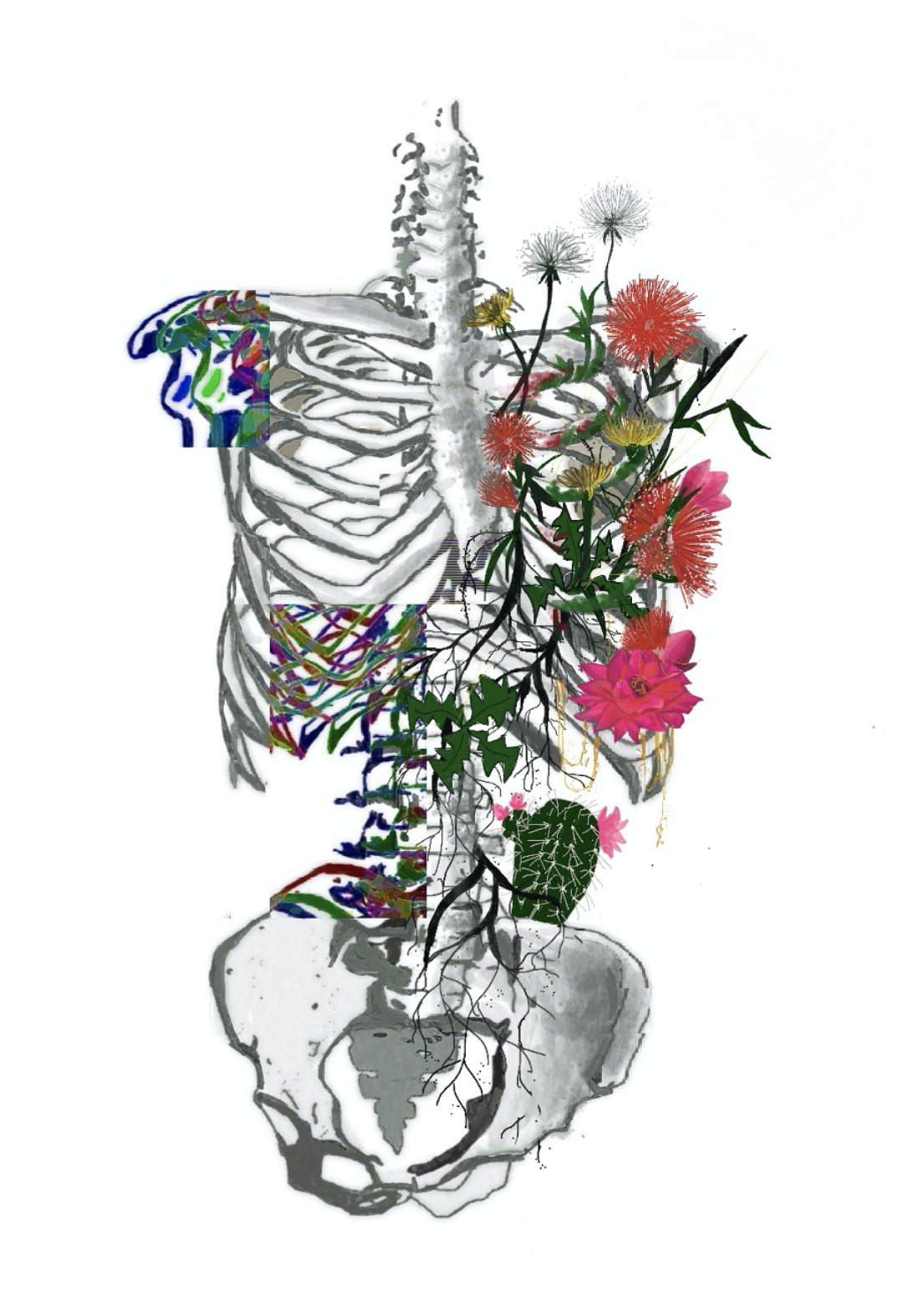

There was an unspoken knowledge hanging in the waiting room air, and no one was looking it in the eye. I held my breath and pictured my own anatomy as best I could. Behind my swollen chest, behind my rib cage and behind my lungs, I would keep the air from telling any facts to my heart.

I didn’t officially know anything.

The persistent ache of my chest fell in with the background noise of orthopedic shoes on tile, distant beeping, and the nurse at the desk typing.

My eyes begged to close. Everyone knows that moms of three-week olds don’t sleep. I hadn’t gotten more than two consecutive hours since Jack’s arrival.

Jack hadn’t been born in that hospital, like me, but up north in our suburb. He’d emerged swiftly with the fifth push, the doctor catching all eight healthy pounds of him at nine at night and laying him on my waiting chest. Megan had come to the room the next morning, so excited. Our two boys, our two second sons. She held Jack and introduced him to his best friend. We unbuckled Jack’s cousin from his car seat and lay them next to each other on my hospital bed. Five months old, her tiny Miles seemed a giant next to my wrinkled newborn Jack.

Megan’s surgery was only supposed to be an hour or so. If I fell asleep, maybe I’d miss the next part. All I wanted was to fall asleep.

Patrick wasn’t back yet.

I willed my legs up and edged out of the waiting room. I walked out towards the restrooms. I heard him before I turned the hallway corner.

Inside the men’s room, Patrick’s fists slammed the push handles on each sink as soon as the faucets had the nerve to shut off. Mist splattered the mirror as he spun on the stall doors, slugging each one in turn to swing on its hinge. Some were already dented.

When he saw me in the doorway, he stared back just long enough for me to cross over and catch him as he collapsed, draping his height over my back.

When you’re 29 and your little brother’s wife is dying, you don’t know how to hold him.

My first marriage had failed spectacularly and ended just as my first son turned one. Carter and I moved in with my newlywed brother and his wife. Patrick and Megan gave us two of their bedrooms and shared all of the snacks in their pantry for six months. Between Megan working nights and my status as an emotional shipwreck, we spent a lot of her nights off watching HGTV in our pajamas, eating peanut butter pretzels and banana chips on her couch.

Right out of surgery, visitors were allowed in Megan’s room. I know now that this isn’t a good sign.

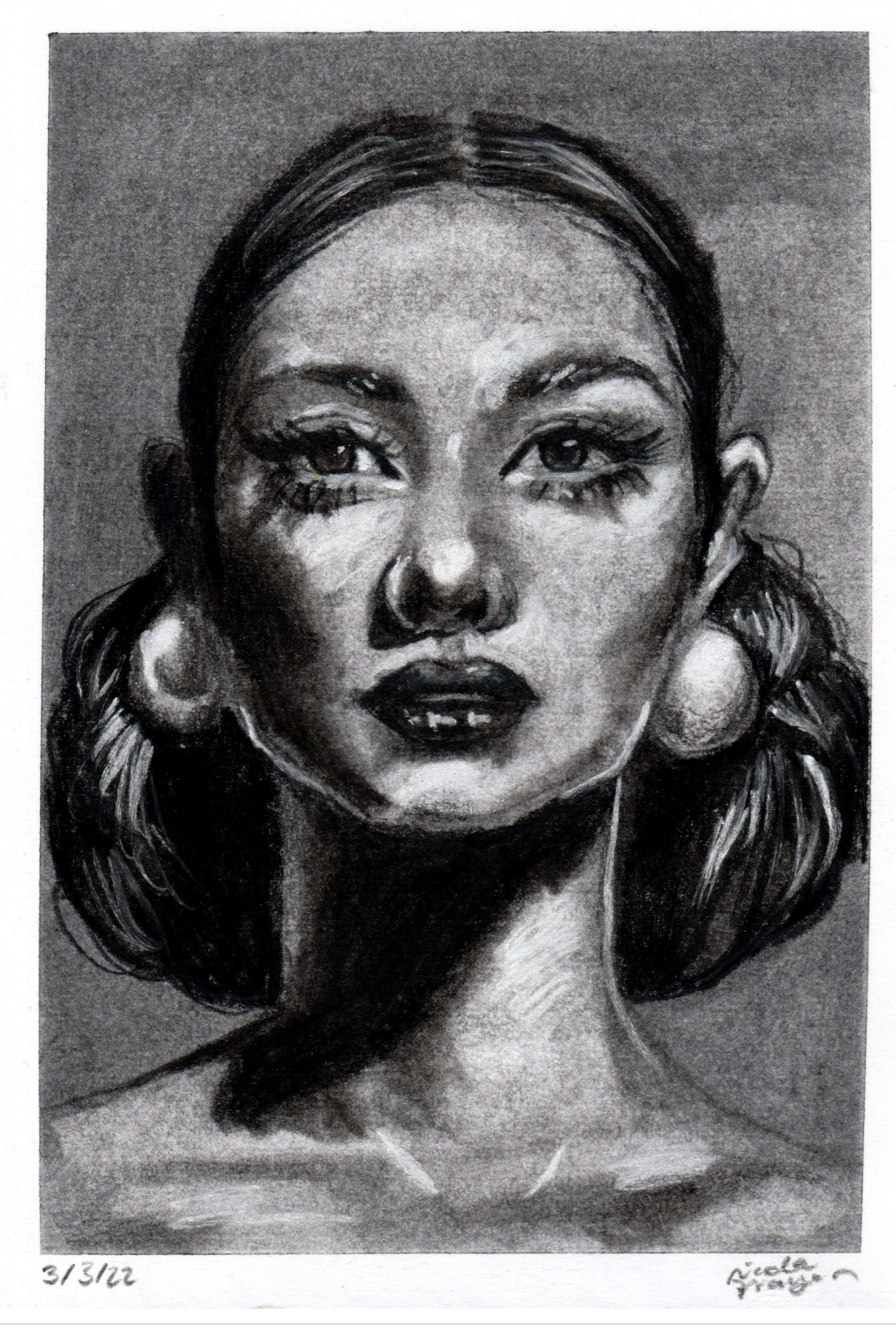

In life, Megan was beautiful. She had shiny dark hair down her back and freckles sprinkled across her tiny, perfect nose. I don’t think she ever fully arrived at the hospital that night, just what was left of her. Her eyes were swollen shut, and her jaw sagged unnaturally. Her neck was bandaged, but everything else from the chest down was strangely unscathed — the strong, efficient torso and limbs of a healthy 26-year old woman. Just a baby herself, really.

The neurosurgeon had shaved the left side of her hair, and I sat stroking the delicate stubble. I lifted her hand and set it in mine. The nurses had cleaned her, but somehow missed her hands. Blood dries to a powder after it sprays, I know now.

“Megs?” I whispered. No answer. Just the rhythmic hissing of the ventilator. “Megs?” Monitors beeped back. Her hand was small and clammy, her fingers limp.

A line formed outside her room. I let go of Megan and told myself I’d have another turn. I’d have as many turns as I needed. That’s what the nurse said. I shuffled sideways out the door, the next person entering as I simultaneously exited, never meeting eyes. Chairs dragged from the lobby lined the hallway. Cousins and coworkers sat on the floor. Megan’s sister sat in their mother’s lap.

The walls around the post-op bed were glass. Every visitor could be watched, but not heard. Megan’s grandparents, married 45 years, held hands as they stood beside the bed. Her mother crumpled to the floor. Her stepdad’s face swelled red, spilling angry tears. My mother pulled socks onto Megan’s bare feet and straightened her sheets. Could she have a blanket? My dad, who had refused to go to church since we were in grade school, waved wildly up at the fluorescent lights, begging.

People acted like they weren’t watching when Patrick went in. He appeared to be negotiating with Megan. He paced, and then stopped, and then paced again, arms and mouth opening and closing at her before he knelt at last with his forehead on hers.

I leaned against the wall outside, willing myself to keep watching. Megan was still here, right here. There were still doctors and nurses working here. There were still grandparents and parents here. There were still baby boys waking up at home.

It registered slowly and then all at once: I was soaked through. My flannel shirt hung heavy and cold; translucent milk droplets collected at the hem. How long had I been like this? Had anyone noticed? I didn’t have it in me to conjure embarrassment.

Again in the bathroom, alone now, I took off my top and wrung the milk down the drain, the squelching fabric releasing a small storm of cloudy rain. I pulled the shirt back on, damp even after being held under the blow dryers. My throbbing chest ached less, but I was shivering and certain that I smelled.

The doctors, followed by the second opinion doctors, lead us into a room with a long table. When they talked, they talked to everyone — parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, the bishop. But they set the papers in front of Patrick.

When you are 26 and married to your high school sweetheart, you’re the one who has to pull the plug if she goes braindead. I know this now.

After nurses turned off the machines, Megan took nearly six hours to pass. Her breath was ragged. Her body fought. An otherwise perfectly healthy patient with a severed carotid artery does not die quickly, I know now.

I also now know that someone, anyone, else has to decide whether to throw out her electric toothbrush or donate her jackets. Someone has to feed the last of her pumped milk to her six-month old and check her calendar for pediatrician appointments.

Years later, someone has to find strands of her hair in the vacuum and the 20 dollar bill she kept in the cookie jar.

Someone has to drive her oldest to his first day of kindergarten, and then her youngest two years after that.

Wise people tell new moms, “The days are long, but the years are short.”

It’s complete and absolute crap. It’s utter bullshit.

The days are long, and the years are long, and all them are so, so full of everything that someone you love is missing. Life, for the living, is long. Time will pass —seven years will pass — even when you’ve pleaded for it not to. I know this, too.

And most of all, I know that an ache in a chest can somehow keep draining long after the plug is pulled.

Heather Lynne Sparks is a tired but hopeful writer, woman, and mother of four. Formerly a public high school English teacher and gifted education specialist, she lives in Phoenix. These days you can find her child-wrangling, typing up her debut novel, and wishing she had a cat.