Mr. Walking Stick

Ron Pullins

“I suppose you also have a walking stick,” I say. “All five-year-old girls have walking sticks. If you don’t have a walking stick, what are you doing being five years old?”

We have decided to take an afternoon walk. Her folks have sent her to stay with us awhile as they try again to ‘work things out.’ Since noon she’s played dress-up with my wife’s clothes in the closet. Now it’s time for us to go outside.

I suggest she leave the slippers here at home, the gold lame ones she likes so much and wears around our house. Clump, clump, clump, if you know what I mean. She likes to wear my wife’s old dresses, too, which are a dozen sizes larger than I imagine she will ever be. My wife’s old clothes are not a style for five-year-olds, but she likes dressing up, being someone other than she is.

“I don’t think you’ll be wanting high heels on our walk,” I say.

That takes some five-year-old thinking on her part, but she comes around at last and returns to wearing tennis shoes. I put bows on them, I tell her, so she will fly if the wind comes up. She says that ought to do. We are on the far side of autumn now, and the ground outside has hardened, but she doesn’t ask about the weather, or the wind, or the temperature. I think she feels herself — with her flying shoes and everything — safely decked out in magic.

She insists on wearing black beads my wife no longer wants. I drape them around her neck, and they dangle to her waist. She also has acquired a noisy wooden bracelet, nor will she leave my house without her purse. She wants to look polite. Who knows but we might stop for tea and something sweet, she says. I imagine that we will.

I put on a scarf. She puts on hers. And we leave by the front door.

We step into a season of wild colors and craziness — of leaves, and clouds, and unstable temperatures. It’s a time of change. By now everyone should have had their harvests and put up food for winter. Birds know that, and trees. I am a great lover of trees, even trees nearly stripped of leaves as they are now. And the birds are fat that fly at night against the moon.

She holds my hand, a way to honor me. Perhaps she thinks otherwise she might fly away. Or I might fly away, and she would want to fly with me.

After some short distance, she asks, “What’s a walking stick?”

She doesn’t talk that much. She rarely asks a question. She is a quiet thinker, keeping all thoughts private, as is common for many girls five years old.

I ask, “Are you inquiring about the common, old, everyday sort of walking stick, like mine, or about some magic one?”

She turns away as she thinks again, as if I don’t notice how she arrives on her conclusions.

“The magic kind,” she finally says.

She sticks to her opinions, once her mind’s made up.

“I figured so,” I say. “Well, the common walking stick, the kind you see most often, helps a person when he walks along. But a magic stick does that, and more. It talks but it does many, many other things.”

“I keep mine in the woods,” she says. “Up there a-ways.”

We follow a path along a creek.

“Then we’ll get it as we go,” I say. “I’m certain we will find it.”

It’s that cool time of day — I like the cool — some few hours before it’s evening. We walk along an unkept wood.

My wife and I care for this young girl from time to time. She seems happy to come and visit us. It’s her respite while her parents work things out, as if things can be resolved. I’m grateful for her company, a pause in my mostly quiet life. I especially like the way she discovers moments, as if her life is a string of them, each unique and a surprise. She is a very brave, young voyager.

We walk along a creek bordered by trees and shrubs. Our walk takes us away from home and our old selves. The day is also nice, if you like crisp, and also a winter’s promise, so there’s that as well.

Black beads swing from her neck as she walks up the hill. And I follow.

We’ve not gone far before she finds her walking stick.

“Just where I left it.”

“Looks like some old limb that’s fallen off a tree,” I say. “But you found a perfect place to hide it. Along this creek. In there with other sticks. Who but you would find it? No one wants their walking stick to fall into a stranger’s hands.”

“Oh, no,” she says. Of that she is quite certain.

Her walking stick is thick, stouter than the walking stick I use, more than what I expect a five-year-old to have. A wild stick, rarely used, I’d say. Gnarled, too, a little taller than my friend herself. No spots worn shiny from frequent wear. She trims it off, as we walk along. She pulls away the dirt and clinging leaves, the loose bark and the twigs. She snaps off the small end to shorten it, and, that done, we take to walking once again, following the creek towards where a hill rises from the edge of town. She is walking with her stick as if they are old friends.

She grips her stick tight. Her hand just fits around it, below a knob where one branch joins the stem as it grows skinnier through a dozen bumps and gnarls.

“You haven’t introduced us,” I say to her.

“Of course,” she says. “Excuse me. Mr. Walking Stick.” She holds the stick upright and out towards me. “This is my father’s friend. We call him Da,” she says to it. “And, Da, meet Mr. Walking Stick. I know you will enjoy each other’s friendship. You’re both good friends to me.”

We walk on. We could go anywhere. There is nothing familiar here; just an old creek, trees, some paths that lead to nowhere in particular. We follow Mr. Stick wherever it is he goes.

She is very nonchalant as she leads the way. She swings her stick most cheerfully, more a friend to swing about than a stick she needs to walk. I am more deliberate with my own. I plant my walking stick down firmly. I swing it out, then lean on it as I move forward. She stops at a stone bench beneath an oak where she waits for me to catch up. I hear her chatting with her friend who is mute to me, as I have said before. Mere silence.

She seems quite happy. I notice that. It is good for her to be outside feeling the birth of winter. She holds her walking stick in front of her, as if her hand is resting on the shoulder of a friend. The string of black beads has been draped around her Walking Stick.

“Those beads look nice,” I say.

“He wanted to wear them, and one must always be polite, you know, and learn to share.”

“So true.”

“We have become such good friends,” she says. “We’ve shared so many secrets.”

“What secrets have your shared?” I ask.

She pauses, then holds the stick away and stares a moment, knits her brows, so serious.

“You must promise not to tell,” she says to me.

When I promise, her finger motions down my ear. “My mother has a boyfriend, and his name is Edward. I’m not supposed to know.”

“Edward?” I say. We talk in quiet voices.

“He’s tall, has yellow hair and drives a truck. That’s a good job, you know. There’s quite a bit of money in driving trucks.”

She leads the way up steps to the Museum.

The Museum is open until the early evening. It sits in all its loneliness out here and casts long shadows. We’ve visited before, but this will be a first for Mr. Stick which, perhaps, is why he’s led us here. The place is small and remains each day the same as it was the day before, but inside they often change things about, so there is always something new to see, or at least some new way to see what we have seen so many times before.

“Mr. Walking Stick has said how much he likes you,” she says to me.

“I wish I could hear him talk,” I say.

“He would like to talk to you as well,” she says. “But although he’s very magic, he can only talk to me. Or maybe only I can hear him. I’ll tell you anything he says, though, and all you want to know.”

“How nice,” I say and thank her.

And I follow them.

Years ago the Museum was built here on the edge of town. It’s little used, a shame. Vines have grown up its stone sides, as if they will escape. The door is thick glass. It seems dark inside. It is quiet when we go in as if silence is the clothes of timelessness.

They allow her to bring in her walking stick in. A necklace dangles from a gnarl. She has tied a string around the middle like a belt.

The Museum has many rooms, slices of the past enclosed in glass along the walls, each capturing a moment — animals in natural habitats posed to kill, or to be killed. Or ancient beings in fur who carry spears and such. Mountains have been painted as the backgrounds — or trees in forests, or a vast savanna in which an ancient family wanders, carrying with them tents and the miracle of fire. We go from case to case and look at each and think our thoughts.

She leads the way. But then she pauses in front of a panorama of trees and ferns. There is a fox with fangs, and lizards the size of dogs. She stares up at an owl that sits serenely on a branch. It’s white and motionless with large and yellow eyes.

“Why, that old owl’s alive,” I say.

“It’s not alive,” she says. She’s firm on that.

“Alive, and very smart, I think. Pretending to be an old stuffed owl, so they won’t catch him here and stuff him.”

She says nothing, but stares at that old owl, and neither of them move.

“Just watch and that old owl will blink,” I say. “We have wet eyes, like that old owl. Sometimes we have to blink. And it does, too.”

She looks steadily at those yellow eyes and says nothing. Then she blinks.

“You see?” I ask, as if I don’t see her. “That old owl blinked.”

She says nothing, but stares at that old owl again. But then she blinks.

“Smart old owl,” I say. “You’d think that it was stuffed unless you knew.”

She doesn’t say a word. For a long time she stands and looks, but misses seeing that old owl blink. Soon enough, she shakes her head and moves on to look at other rooms and other captured moments. She chats with Mr. Walking Stick, discussing what they see. But not with me. I am feeling bad. I’m not sure what I’ve done.

When we leave, I lead the way up the hill. Behind me I hear the rattle of the bracelet and fragments of their conversation. How she contains herself. How any of us do, that is a wonder.

Outside again, she’s hooked her purse on Mr. Walking Stick, as well as the wooden bracelet she has attached to some small twig. I hear them behind me in conversation as I lead the way back home.

Now it is evening. I wile away the time going through my emails and scanning computer news. She sits beneath the kitchen table and drives a car, her walking stick beside her, as she steers through evening streets. She passes by a store and points out to her stick that this is where she buys her shoes. She points out the ice cream store, of course. She honks at some young child who nearly runs in front of her. I read the evening paper.

Before she falls asleep she bears a forlorn look, a sadness, like a fog around your feet that closes up as you walk through. She gently lays her walking stick beside her on the couch, then looks at me while her eyelids sag. “We just had to get away, didn’t we?” she says. “From all of that.”

It’s evening. The doorbell rings. Her mother has come to fetch her home. Her parents separated that afternoon I hear whispered. This time forever. I see the bruising where her father’s held her mother’s wrists too long. They prepare to leave and after some debate, my young friend is allowed to bring Mr. Walking Stick along. Just as she is leaving my dear friend beckons my ear down again.

“I knew that that old owl was stuffed,” she says. “Mr. Walking Stick told me so.”

She runs outside and they drive off.

I haven’t seen her now for years. I still take walks and when I visit our old haunt, I sometimes stare and wait for that old owl to blink. It never does, however much I wish it would and that I had not betrayed one quite so young.

Ron Pullins is a fiction writer, playwright, and poet working in Tucson AZ. His works in fiction, poetry and drama have been published in numerous journals including Typishly, Southwest Review, Shenandoah, etc. A list can be found at www.pullins.com. He is very proud to be part of the inaugural issue of Chariot and wishes it a long and happy life.

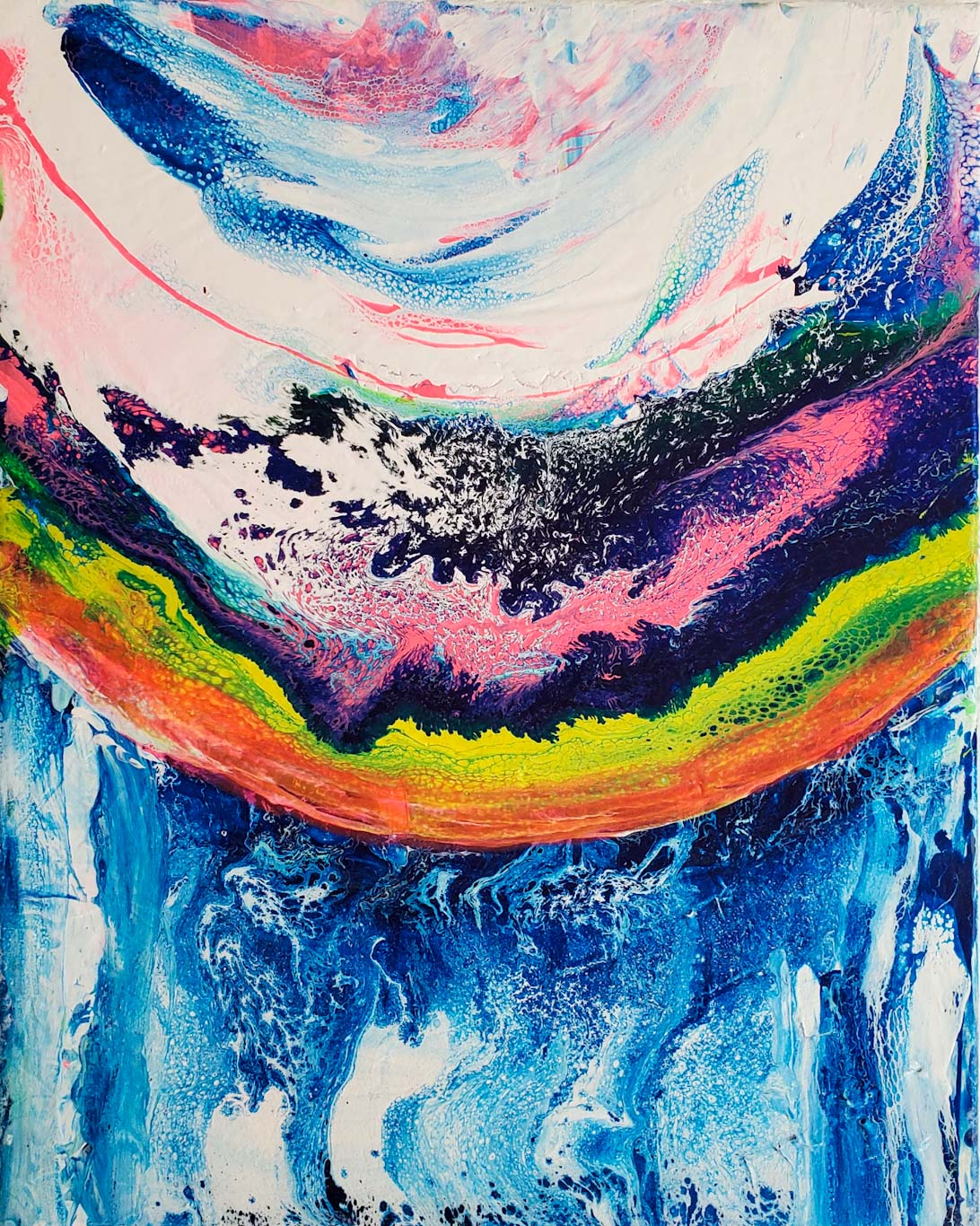

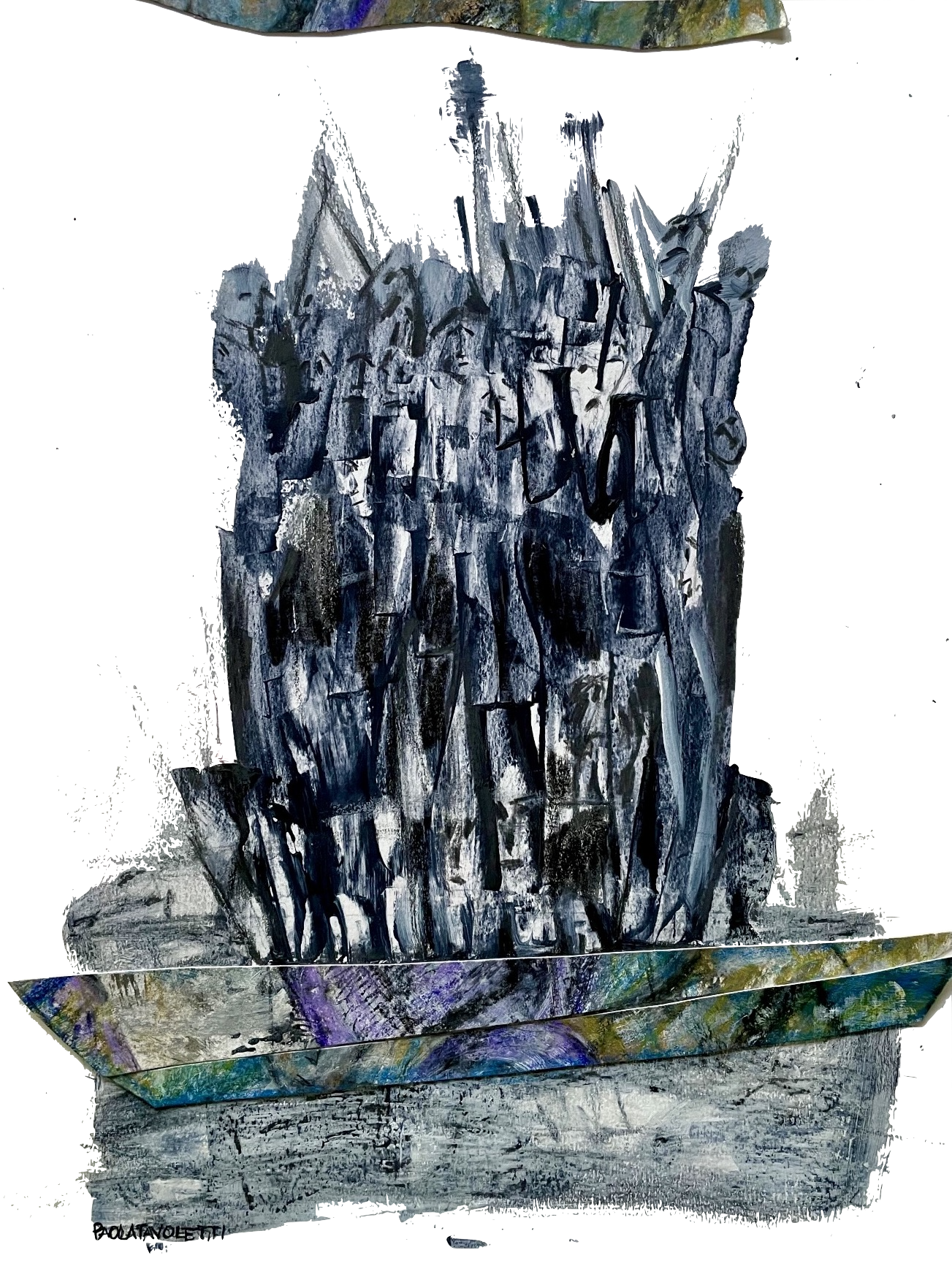

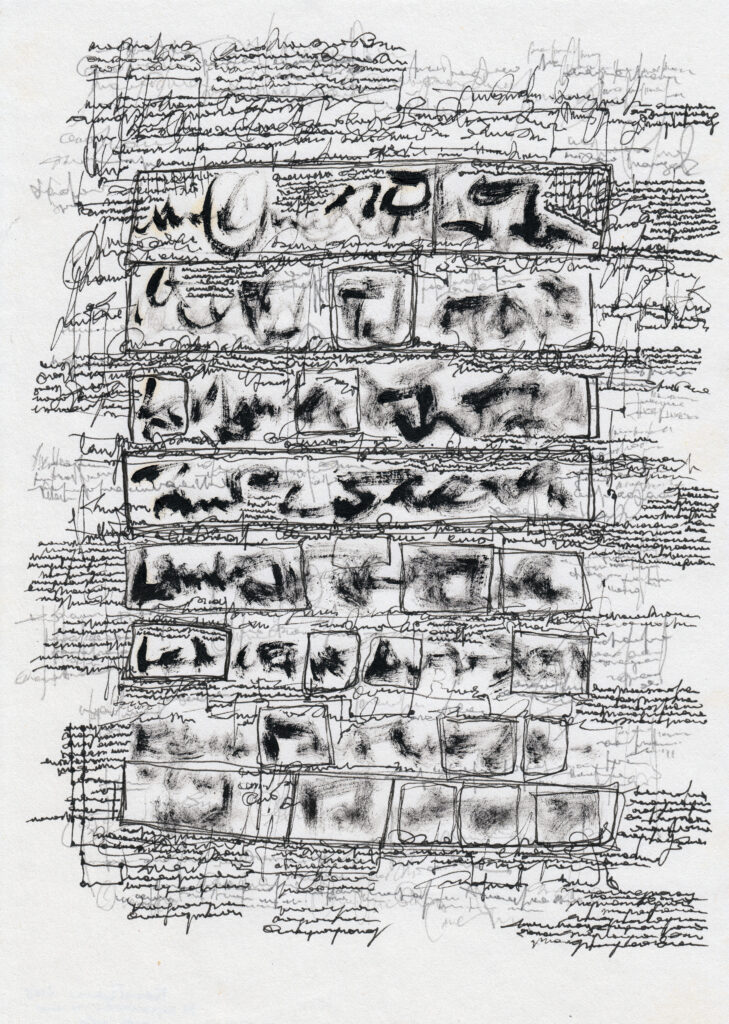

Art: Singing Thicket by Cynthia Yatchman who is a Seattle based artist and art instructor. A former ceramicist, she received her B.F.A. in painting (UW). She switched from 3D to 2D and has remained there ever since. She works primarily on paintings, prints and collages. Her art is housed in numerous public and private collections. She has exhibited on both coasts, extensively in the Northwest, including shows at Seattle University, SPU, Shoreline Community College, the Tacoma and Seattle Convention Centers and the PaciNic Science Center. She is an afNiliate member of Gallery 110, a member of the Seattle Print Art Association and COCA