Dot’s Tangle

Elizabeth Quirk

“Tell me about when I was born,” Dot requested one night toward the middle of seventh grade, laying her head on her mother ’s lap and willing her to play with her curls, soothing its tangle just as she had done when Dot was very little, each minor ringlet receiving its due. Unlike some girls her age, Dot did not in the least alter —whatever the other ways she was rapidly altering— her childish tendencies to be petted, adored, fussed over. Nor did she tire of hearing about the drama that surrounded her earliest existence; it not only mollified her vanity with its gravitas but hearing about her early mortal peril from the vantage of her current long-limbed vitality made her feel immeasurably safe. Then she was like the baby lamb asleep in a gothic tapestry, eternally embraced by its benevolent dyed-thread jungle. But other times, when she was alone and especially on pale afternoons, if she seriously contemplated the circumstances of her birth — in fact a near-death— she felt lightheaded, dizzy, tenuous. I-might-not-have-been and I-nearly-was-not would come careening with alarming lucidity to the forefront of her consciousness, sending the room spinning out of focus, and what could be solace became pure disorientation, all threads unraveling, even those at the center of her spine. (Metal, silk, and wool, weld, madder, and woad, fading and blowing away like ashes.) Then a frantic attempt at reclamation: I-am-here, I-am-me, and her name, like a summons— Dorothea-Jane-Claudel; Dottie, Dotsy, Dot— met only by whirling incredulousness and dust. She often had to lie down, her face pressed against the fabric of the living room couch, inhaling deeply its scent, before she returned to herself.

“You were so tiny; so impossibly tiny that Daddy could hold you in one hand, like this,” came the familiar narrative, and Dot’s interruption: “No, Mama, start from the beginning, with the apples.” She loved the clink of her mother’s rings as they knocked together in accompaniment to her voice, which for Dot was older than memory. Vomit and blood. Not blood, only red apple skin. Elsa’s tone changed slightly: “Of course, it was too soon.” From that very first instant, when that might have been all there was, an infant quickly taken away, to now, when her daughter had reached the mysterious and dangerous borderland of childhood, ears pierced and toenails painted, she had known that Dot was her own person, separate and entire. Only during those too-few months inside her had she ever belonged to Elsa completely, and maybe not even then. Now she could acknowledge with a warmth that was almost lightness what had once been so raw and terrible.

The second baby had come at 3:12 A.M.; Thomas Matthew Claudel was born in the caul like a present still wrapped and what centuries ago would have fetched a sizable sum on the luck charm market was quickly pierced. “He did not cry,” her mother recalled simply and Dot nodded; when she was born, she had pierced the air with her first wail, like she was supposed to, but her brother had not because he could not. There were other facts (remembered in faint tremolo): His eyes were gray and wide apart, the mirror and match of hers. He weighed only three pounds, three ounces; she weighed even less. They had terrifyingly minute arms, legs, fingers, toes, and like uncanny dolls, their skin had a translucent glow. “Can you imagine being so small?” (Dot could not.) A visitor had brought her brother a plush giraffe and it topped the strange antiseptic space of his incubator. The same person gave baby-Dot a gray elephant with pink velvet inner ears. In a near-whisper, Elsa recalled how her little son— her only son— had held her thumb with his entire hand and gazed straight at her; she had looked at him and he had looked back and from that moment, she was smitten, gone, lost. (Time stumbles; handfuls of crumbling dirt.) He died in her arms six days after being born, at 7:08 p.m., never making it to a second Monday: MON. TUES. WED. THU. FRI. SAT. SUN.

For the first time, something within Dot snagged while listening. Her barely childish body, her restless, roving mind, knew hardly anything outside the gentleness and care conveyed by the maternal hands above her, but still oblivion waits. We-never-were came like a reckoning, and its devastating follow-up: we-almost-were, we-nearly-were. In another time, a different place, she too might have died so soon. But that wasn’t what brought anguish; not possibility, but actuality now tore her asunder. Dot was like the long-ago ancient listening to its creation myth under the familiar canopy of night sky and only at this, the nine-hundred-and-ninety-eighth time, being brought to tears by those old sorrows drawn out in the stars and suddenly lived in the throat, in the heart. To weep for gods, for ourselves. Tom (wouldn’t they have called him that?) who had likely been conceived at the same instant she was, issuing forth in unison from nothing to something and sharing everything in that early darkness, was gone before they could know one another. They never held hands while running or laughed at a joke or exchanged knowing glances or fought—or anything at all. “Dorothea, you will always be a twin; nothing can change that.” Dot shut her eyes. What is a zebra without its stripes? The jellyfish pricks at the center of her being sparkled in a crescent before fading and washing over her until even her cheeks were wet. “Oh, darling,” Elsa said, gathering up and rocking the little girl she no longer was, or hardly was.

Dot dreamed of him for weeks in a row, his gray familiar gaze blinking back at her, the two of them almost identical, like two bright-eyed lemurs, and the sky never the same, always shifting color and shadow. For now, just this was enough, an initial reclamation (then we fall from the branches of trees, trees, trees).

Elizabeth Quirk won the 2021 James Hurst Prize for Fiction and teaches literature and composition at Wake Technical Community College in Raleigh, NC. She lives with her husband, two black cats, and a beagle.

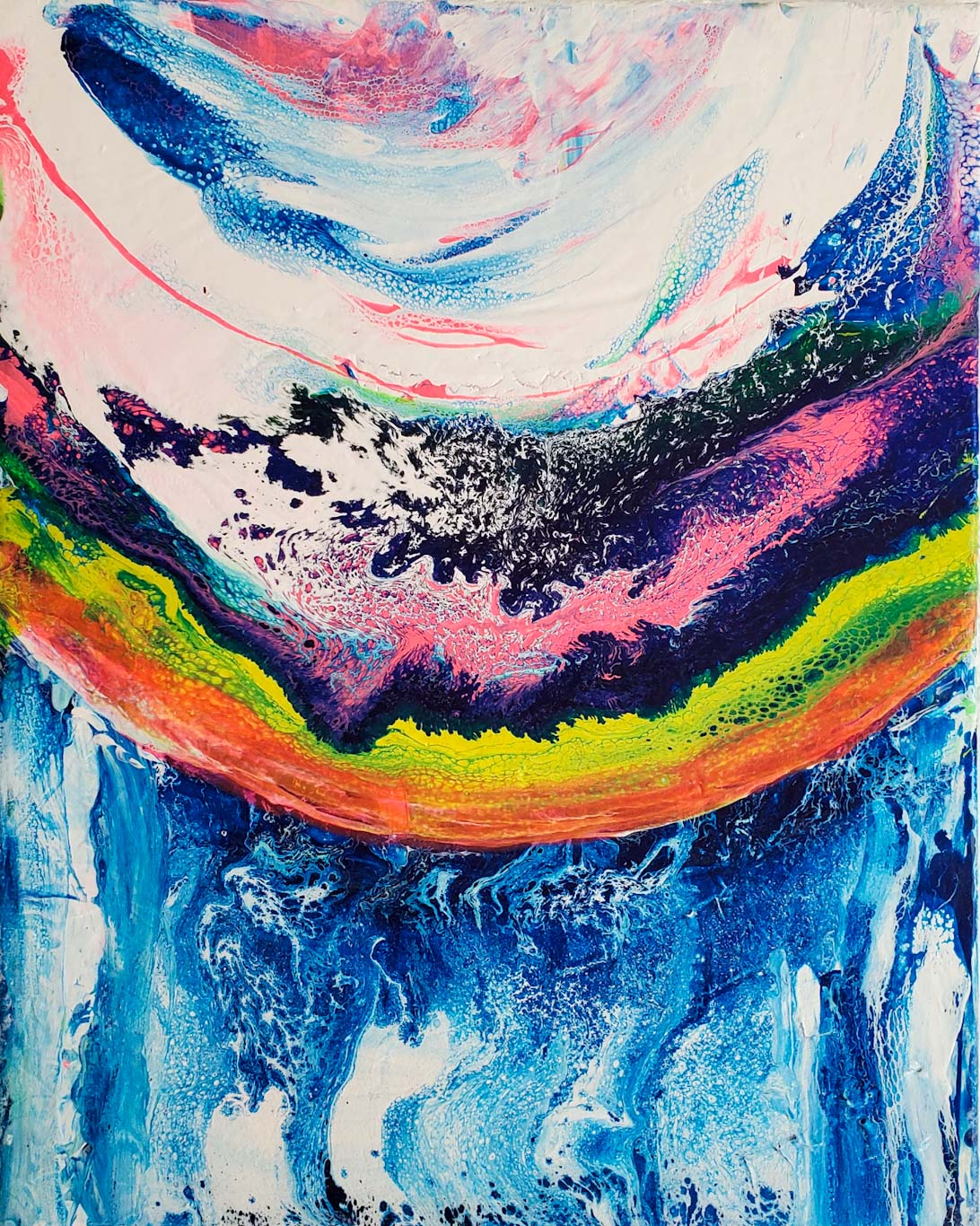

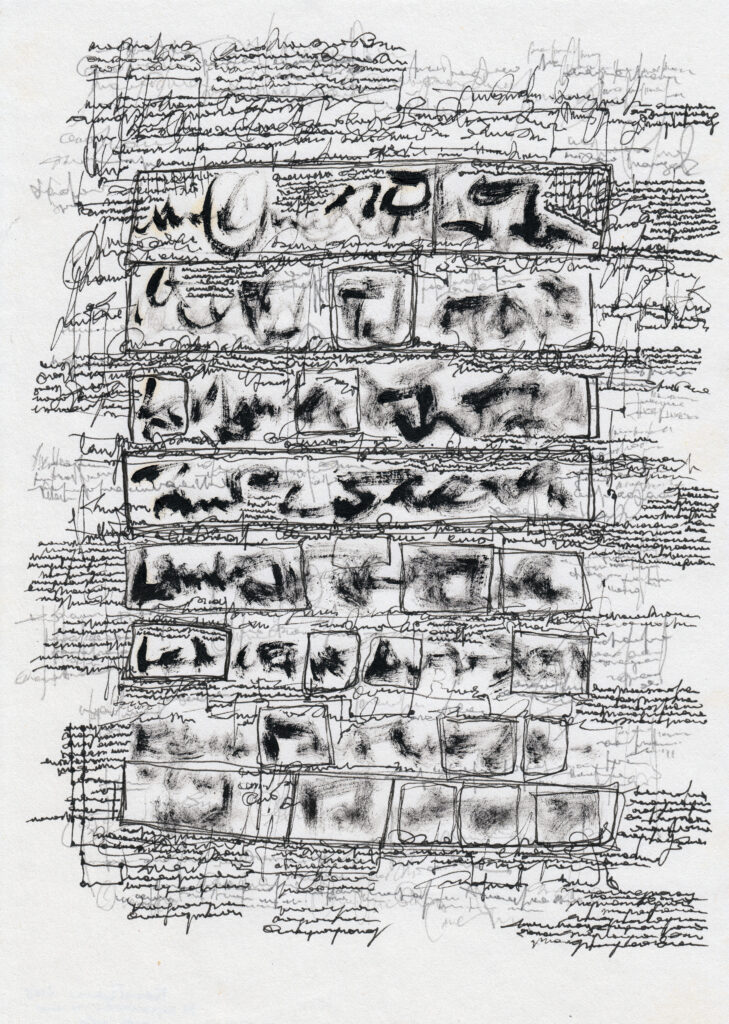

Art: Fun in Space by Anthony Afairo Nze who is an artist and graphic design student from Indianapolis. For more of his work visit him at afairosgallery on instagram.