Costa Rican Coffee and Empanaditas de Piña

Mary Sobhani

Once upon a time, in Gainesville, University of Florida, there lived a Hoosier, Indiana farmboy, transplanted to the halls of Gator grad school, hardworking like those John Deers, humble like the earth he’d plowed since he was seven.

Once upon a time, en Costa Rica tierra hermosa, there lived a Tica, a city girl, with a certain way of finding laughter in the air and kneading it, multiplying it, sharing it, compartiéndola con gusto, just like one does with empanaditas de piña.

I could say Martha was beautiful, como las rosas de Cartago, and that John was handsome, William Levy meets Ryan Reynolds (like in Free Guy, not Deadpool). But you might think I’m lying, or worse, dealing out bad clichés. So instead, picture it: July in Gainsville, land of mango sunsets, 1967.

John left his small apartment, luggage in hand, locking the door behind him. He wasn’t thinking of love. He wasn’t thinking of adventure. He was thinking of the field work that awaited him on the Costa Rican coffeebean plantations, the data that awaited his collection, and the dissertation that he’d complete afterwards. He figured his Spanish classes were about to be put to good use.

Two days later, in San José, Costa Rica’s rainy season (but the good rain, the kind that only starts after 2 p.m.), Martha was sipping coffee with her mother when the phone rang. It was Martha’s friend asking her to go to a party: “Ven a la reunión esta tarde, amiga. Llegó un gringuito.” Fresh off the plane, she said. Newly come to San José, a North American, all set to research Costa Rican coffee beans. “Le podés hablar en inglés,” the friend insisted. She knew Martha’s English was superb. Martha paused, considered, declined. She was a school teacher, twenty-five, and with no time for flings or foreigners.

Fate, however, like a good coffee, is hard to ignore when brewing.

When the doorbell rang later that evening, Martha shouldn’t have been surprised to find her friend. And her friend’s cousin Felipe. And – behind them – the American.

John fell in love with a clap-of-thunder, an eyes-dilating, pit-of-the-stomach-feeling, flash of knowing. Usually John was of the mind to tread with care, to proceed with caution, to walk the ways of the world in balance and moderation. This was not to be one of those times. When the evening was over, John abandoned caution. Audacity prevailed: “Can I call on you tomorrow?” John asked Martha. And Martha rather startled herself when she said yes.

The next afternoon, holding claveles and alhelíes, John appeared, flowers and heart in hand. Martha was bemused. Dinner. Walks in la Plaza Principle. Movies. Bowling (although they never actually bowled; there was just too much to say). And every time John picked her up, he entered with blooms in a ribboned bundle and a shy smile in his eyes.

On a city bus in San José, ten days after setting foot in Costa Rica, land of beaches and cloud forests, of volcanoes and hummingbirds, John proposed.

Martha sat back in surprise, the downtown buildings slipping by the bus window, unseen. “Estás loco,” she said. A proposal? On a city bus? He must be a crazy American after all.

A month later, the Hoosier left from Alajuela, flying back to Gainesville and grad school with his dissertation and a Tica on his mind, and one would have thought that he would have been defeated, dejected, depressed… after all, Martha has declined his proposals. Every single one of them. Every single time.

But John felt victorious; Martha had agreed to write to him. August passed. September and October, too. Letters traveled via aeria from Gainesville to San José and back again. John was certain that fireflies had never been so bright, that the University Gardens had never looked so green, that McCarty Hall had never looked so beautiful.

In Costa Rica, November began with the red-white-and-blue-edged envelope newly arrived in the mail. Martha opened it with a shiver of anticipation, of seeing John’s handwriting on the page, of reading his spirit entwined with the loops of his words. And she knew right then. “Mami, me voy a casar con él.” Her mother nodded sagely over the flour, piloncillo and finely chopped pineapple. Finally! She had already let Martha know she was a partisan of the shy flower-toting gringuito con ojos verdes.

In Gainesville, as chilly as Novembers ever get in Florida, the letter John hoped would come finally arrived: the one with yesses in its ink, in its lines, in its curves and in its edges, in its spaces, in the leaning of its vowels, in the timbre of its words. John purchased his plane ticket with a departure date scheduled as soon as the semester was over.

It’s 2021, a new decade in a new century. John is wearing his coffee-and-pastries suspenders today, and the mango-orange shirt Martha got him for his last birthday.

“Dad, what made you decide to propose two weeks after meeting Mom?”

He grins, eyes crinkling at the corners. “She was nice, a real cute girl.” It’s an understatement like no other; I’ve seen those old black-and-white photos of Mom, gleaming black eyes, ebony hair, eyebrows to die for. Dad looks into the past, and I can almost see the shy grad student he had been.

“It was less than two weeks,” Dad admits, shifting the uke he’s holding, to give the memory its due.

“What did Mom say to that?” I ask, fascinated at his daring. Dad strums. “She said, ‘Estás loco.’ You’re crazy.”

“How’d she say it?”

He grins and his fingers strum out the firsts chord of “Screwball’s Love Song,” one of his favorites. “Just like that.”

Dad’s eyes, gray more than green now, have a sly twinkle. “I asked her if I could write to her before I left. I knew my written Spanish was better than my spoken Spanish.” He chuckles, like he got away with something. I suppose he did. In those snail-mail days before Zoom and Skype and Facetime and Instagram, letters were the bridges of the heart, after all.

Martha joins us at the kitchen table, holding coffee and a plate of pineapple pastries. She scoots in next to Dad. There’s always room for her next to Dad.

“Mom,” I say, turning to her, “what do you remember from when you first met Dad?”

Martha looks at John. Her hair is only gray at her temples; the rest is still that glossy black. Just ask, and she’ll tell you proudly she doesn’t dye it. “Oh, he was handsome,” she says, leaning over and placing a kiss on Dad’s cheek. “And, you know, he looked so cute coming up the steps with a bouquet of flowers for me. He did that every day, you know. Every single day until he left to go back to Florida.”

They exchange a look that has 54 years of coffee and empanaditas and heart-songs behind it.

“But, Mom, if you liked him, why didn’t you say yes right away when he proposed?”

“I needed to be certain he was sane. And that he meant it.”

“And then what did you do?”

Mom’s eyes widen, remembering, and then dimples appear: “Ay, mamita, I planned my wedding!”

I could say that John and Martha, that Hoosier and that Tica, lived happily ever after … but only as long as we’re clear that saying so includes the hardships too: the tears of four miscarriages, the loss of the farm, the joy of a daughter and a second surprise-daughter fourteen months later, the making-ends-meet

and sometimes not,

the learning

coping

growing

failing

crying

stewing

talking

laughing

striving

loving

and Costa Rican coffee with empanaditas de piña.

Translation of Spanish words:

- empanaditas de piña = pineapple pastries

- Tica = national nickname for a woman from Costa Rica

- tierra hermosa = beautiful land

- compartiéndola con gusto = sharing it with pleasure

- como las rosas de Cartago = like the roses of Cartago

- Ven a la reunión, amiga = come to the get-together, girlfriend

- Llegó un gringuito = A North American has arrived

- Le podés hablar en inglés. = You can talk to him in English.

- Claveles y alhelíes = carnations and Erysimums

- Mami, me voy a casar con él = Mom, I’m going to marry him.

- piloncillo = brown sugar

- con ojos verdes = with green eyes

Mary A. Sobhani was born in Costa Rica and raised in a bicultural home. A career educator, she lives and builds community in Arkansas, the beautiful Natural State. Her poems, essays and articles have been published in the Journal of Interdisciplinary Humanities, Acentos Review, Interstice, Chasqui, Hispanic Studies Review and @Urban Magazine. When she isn’t writing and teaching, she enjoys Baha’i Studies and K-dramas, and she adheres to the famous Persian Educator Baha’ullah’s words of wisdom: “Let your vision be world-embracing.”

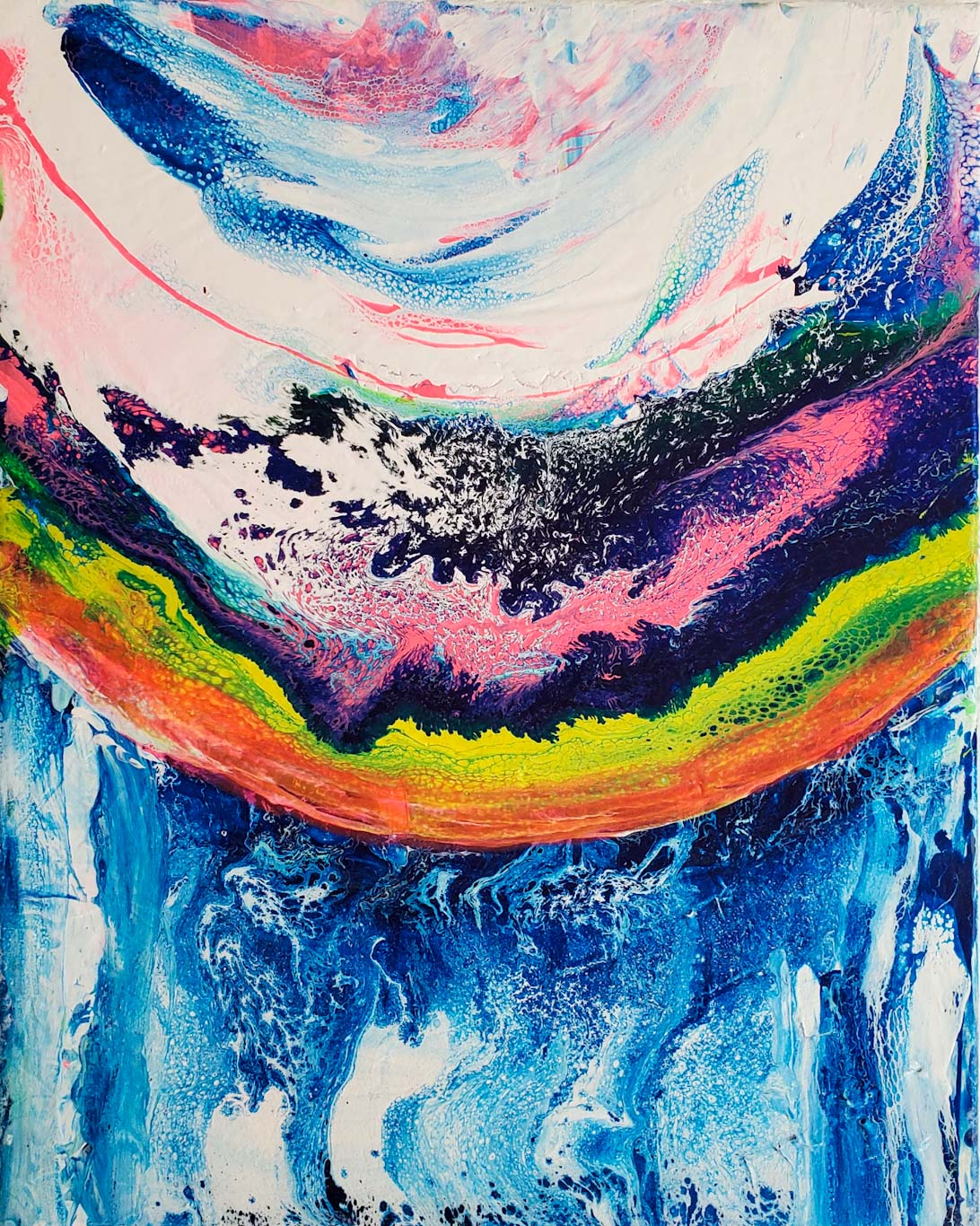

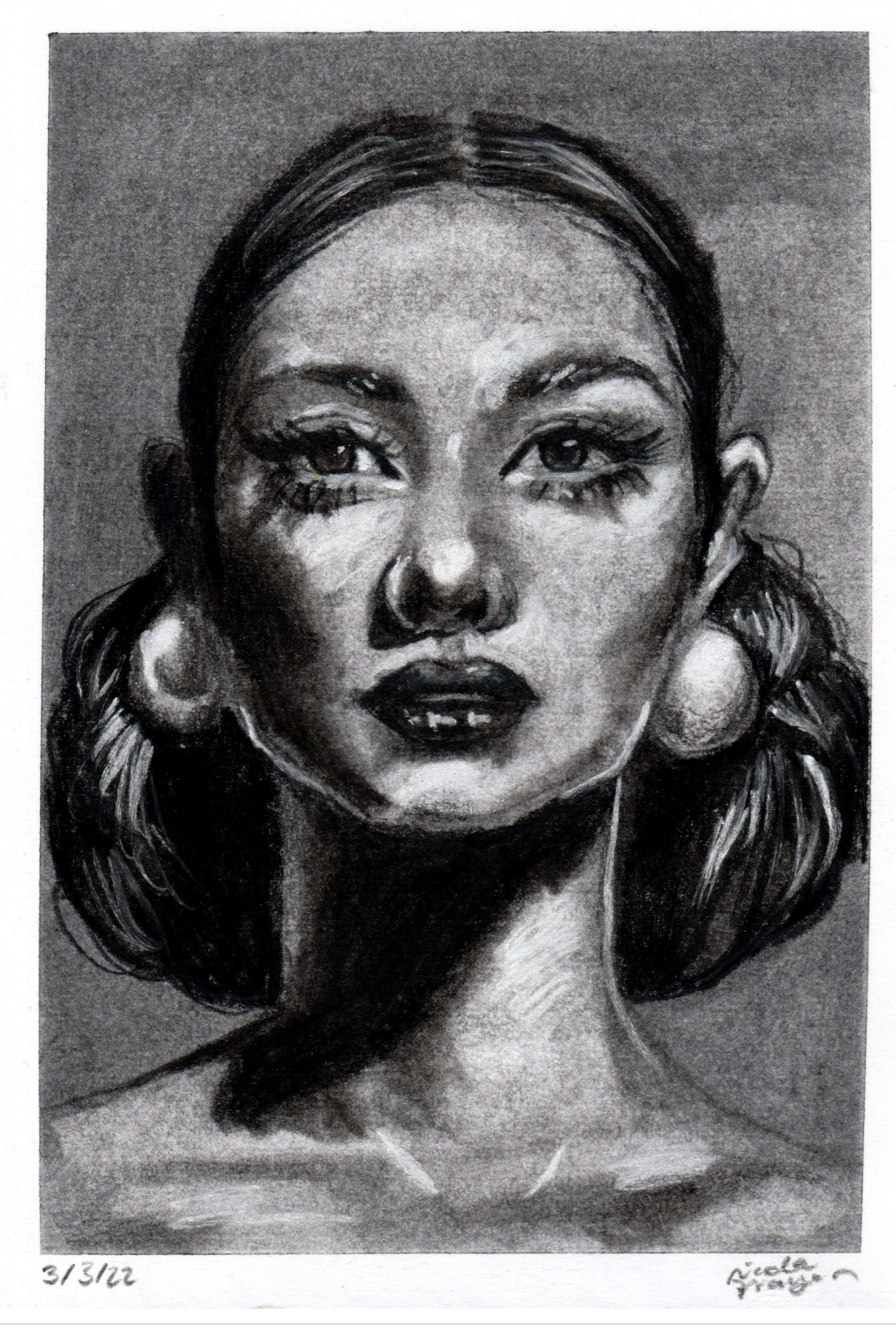

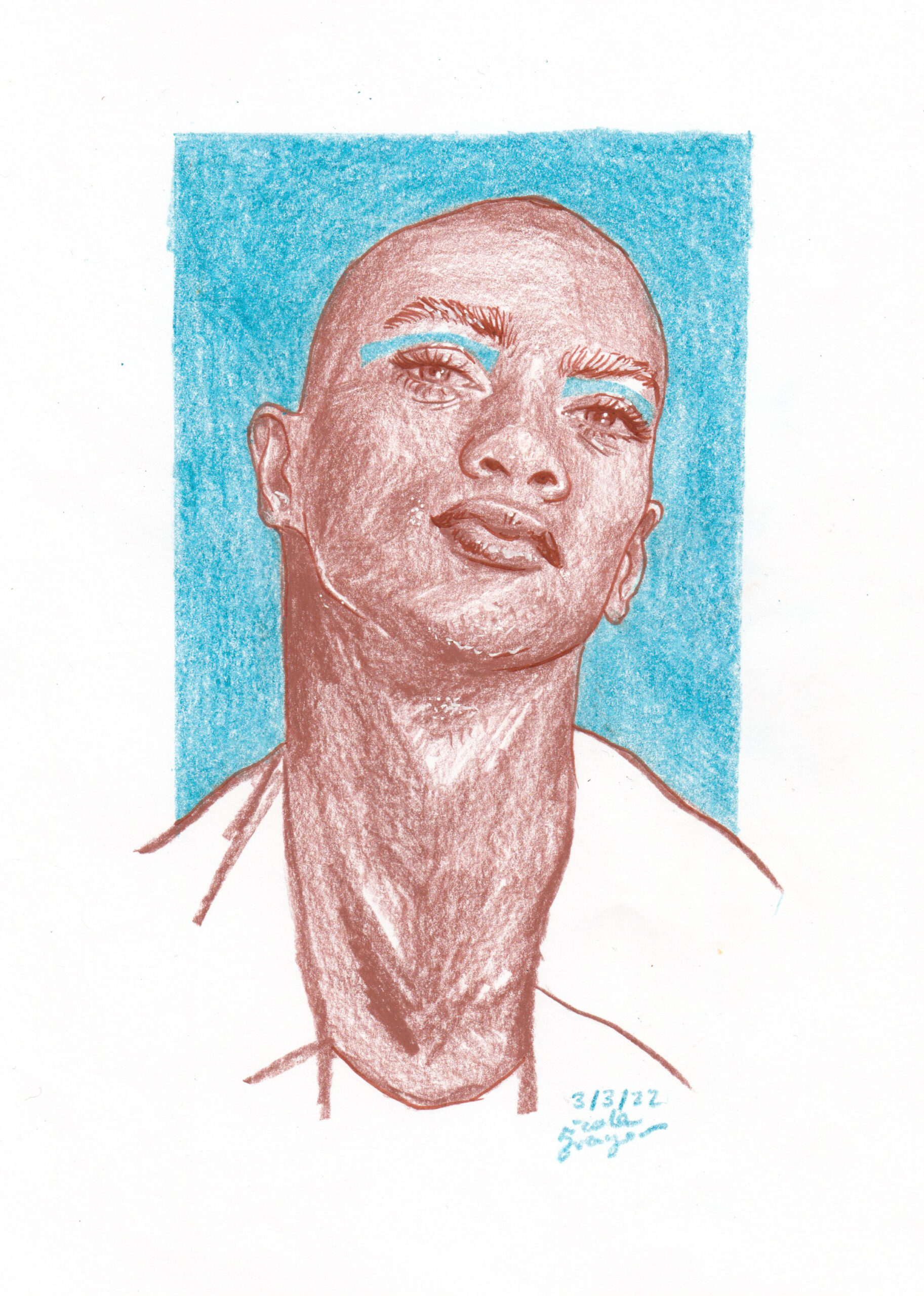

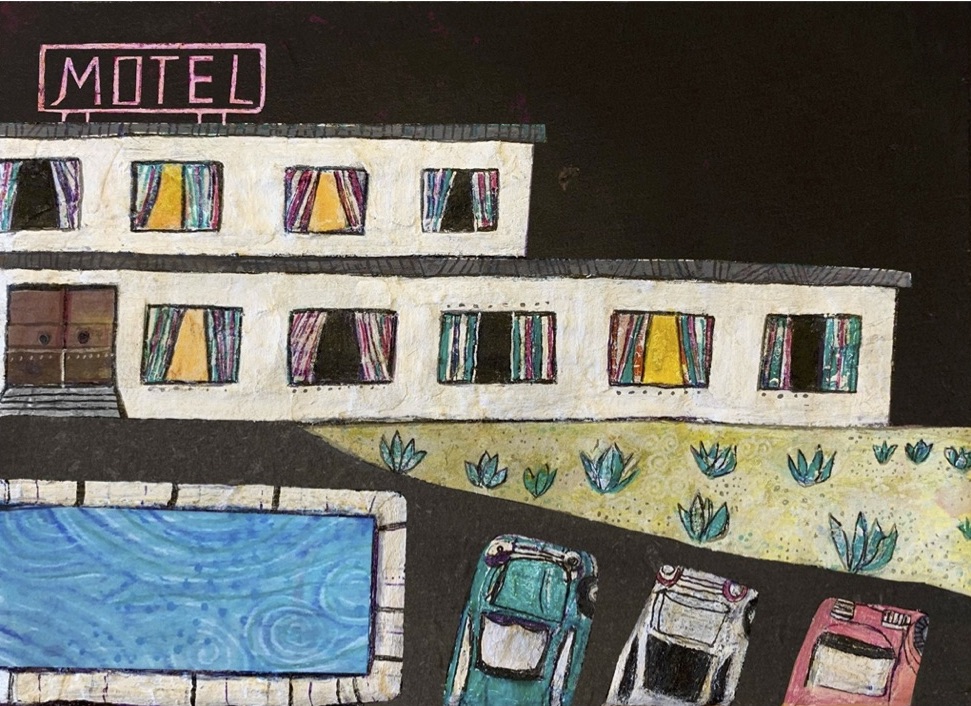

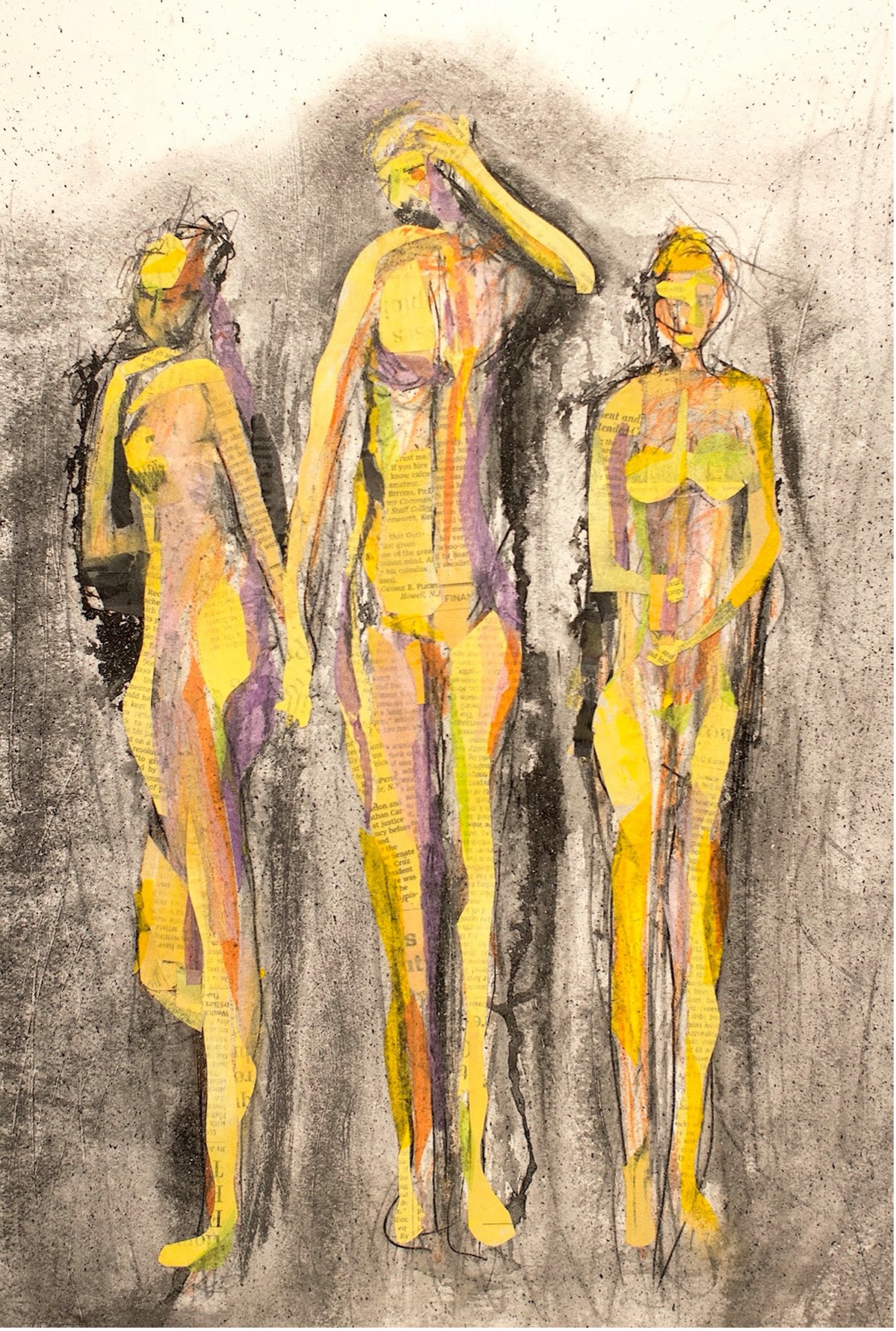

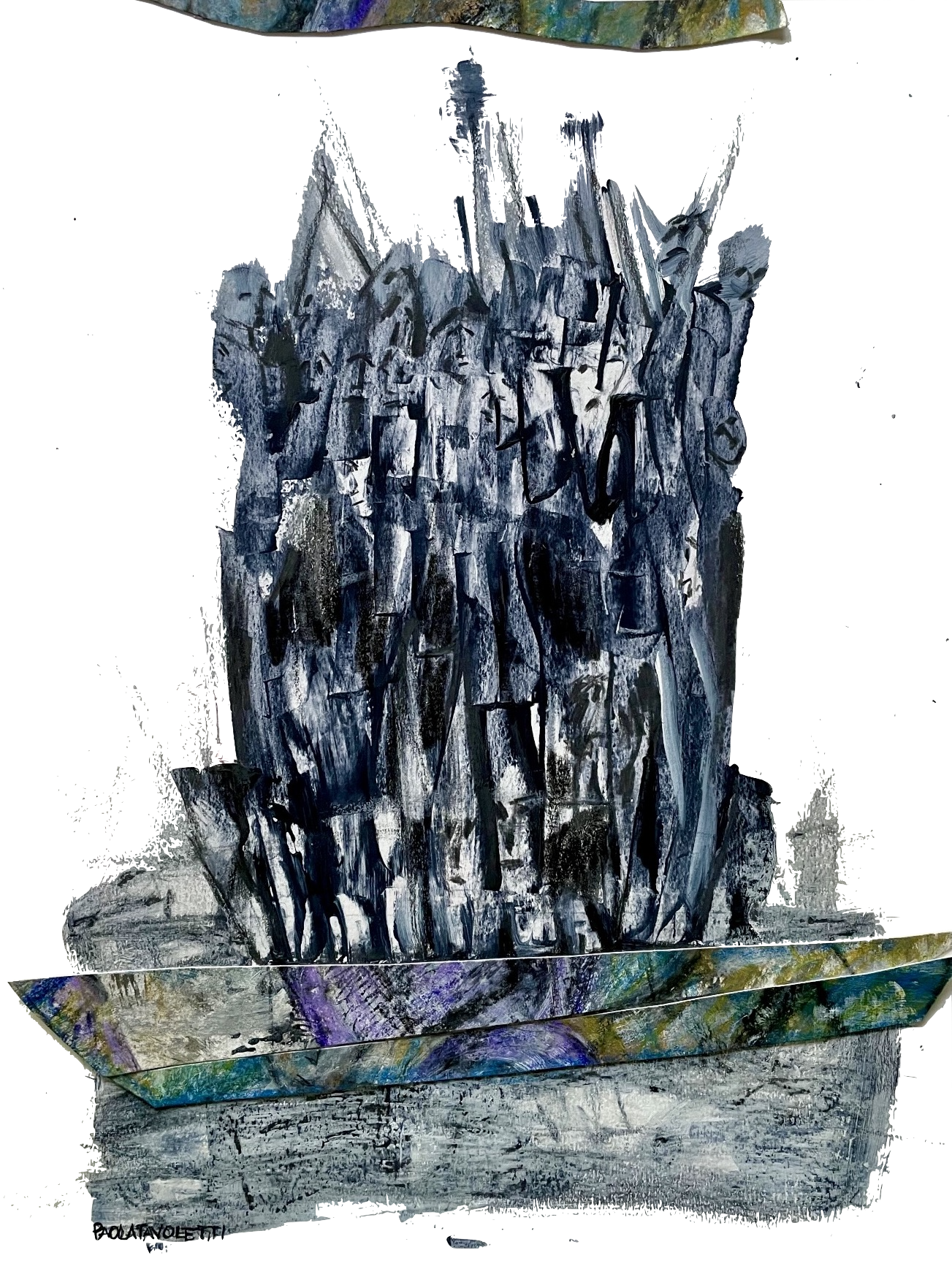

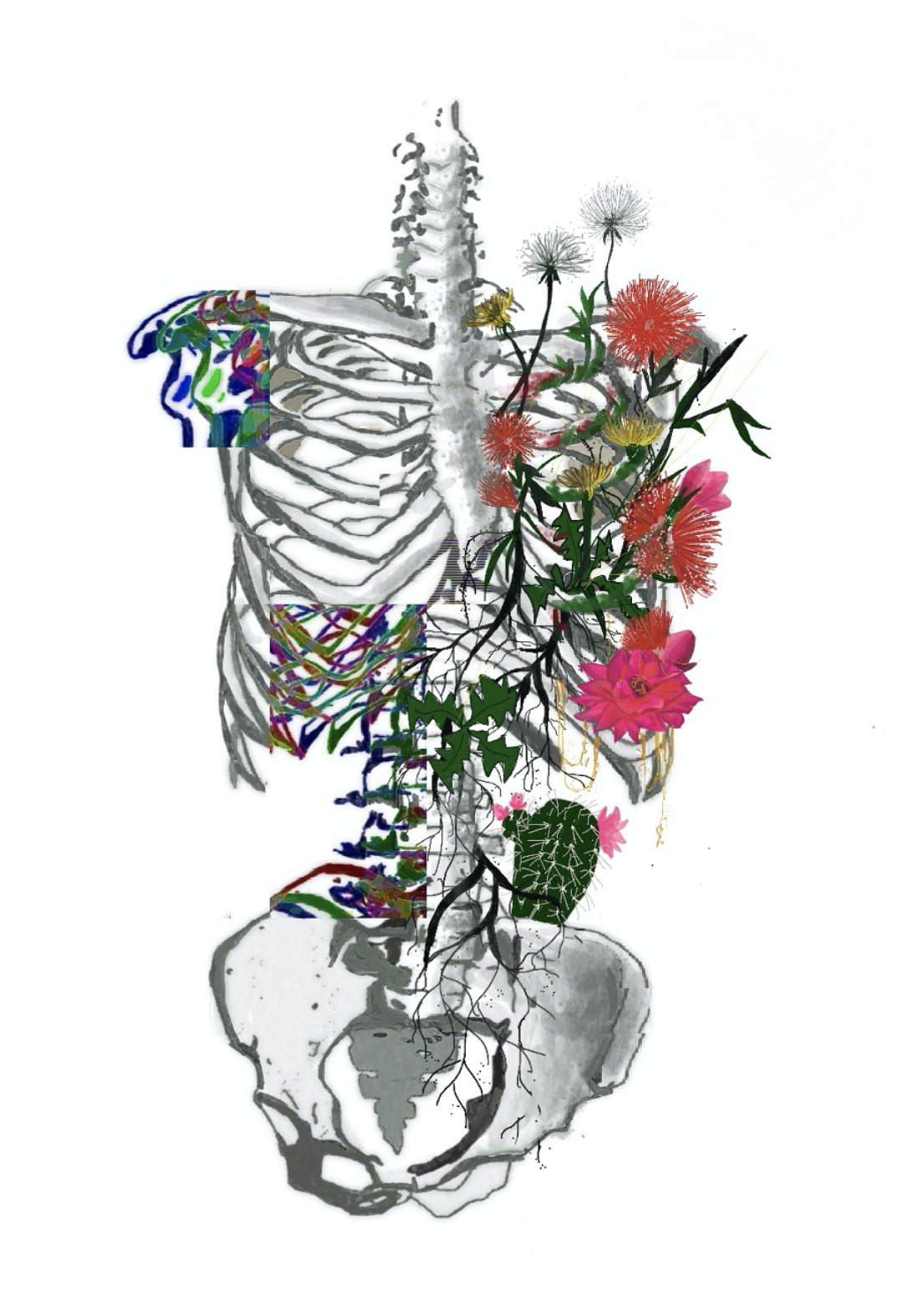

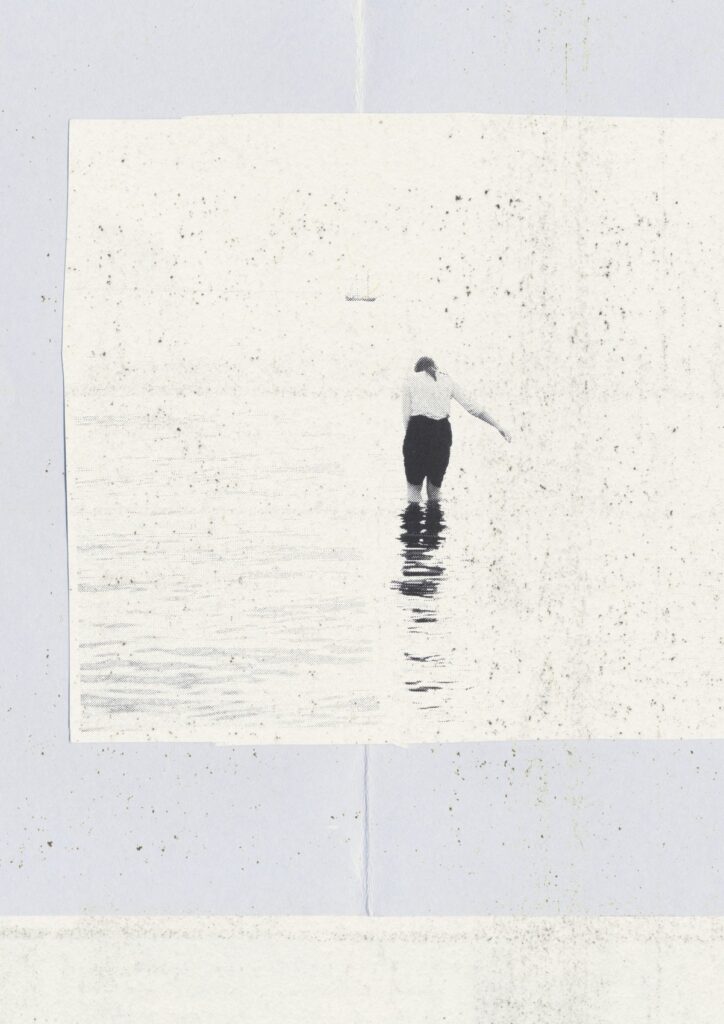

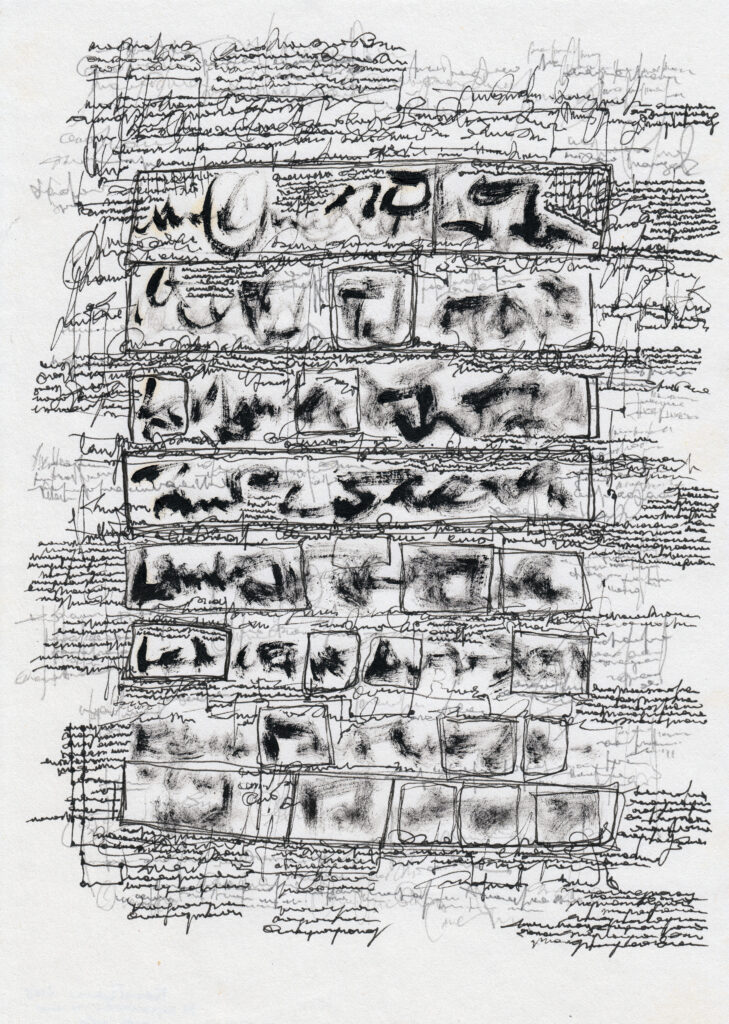

Art: 22 Pieces on a Single Note by Federico Federici who is a conceptual artist working in the fields of writing, video art, installations and physics. He is currently based in the Ligurian Apennines. His works have appeared in international journals and anthologies including «3:AM Magazine», «Art in America», «Diagram», «Perspektive», «Jahrbuch der Lyrik», «Poet Lore», «Sand», «The Shanghai Literary Review, «The Manhattan Review» and others. His latest books: “Liner notes for a Pithecanthropus Erectus sketchbook” (LN 2018), with a note by SJ Fowler; “A private notebook of winds” (Academy of Fine Arts in Palermo 2019); “Transcripts from demagnetized tapes” (LN 2021); “Biophysique Asémique” (LN 2021); “Lettere d’amore a Peter Rabbit” curated by Paolo Giovannetti (Zacinto 2021); “Profilo Minore” curated by Andrea Cortellessa (Aragno 2021); “Maß des Schlafes (und andere verbovisuelle Forschungen)” (Anterem 2021). His forthcoming work is the visual poem “EIS”, with a critical note by Peter Schwenger.