Blisters

Joshua Harris

The night the blister beetles swarmed, we’d had a quick, early dinner at a restaurant down the road. We were seven Peace Corps volunteers in Mali, West Africa, spending the night at the Mopti stage house, a mid-county bunkhouse for those of us in need of a night away from the village or a place to lay our heads before continuing south to Bamako. We bought big bottles of Castel. The resident volunteer pulled out his guitar. The night promised Kumbaya—not the cynical version of today, but honest togetherness. We settled into mismatched furniture, cracked our beers, and watched the desert light fade from the relative comfort of a semi-screened-in porch. I say “relative comfort” because, though we’d begun to acclimate to the desert’s unforgiving temperatures, the heat that night lingered like an unwanted guest, serving as our first warning of the approaching “hot season.” As darkness creeped its fingers into our small circle, we fired up the generator, illuminated the single bare bulb hanging from the porch’s thatched overhang, and began to commiserate about our common struggles en brousse.

First, we heard the fluttering—a far cry from the constant trill of mosquitos to which we’d grown accustomed. And they were large, these insects, and rapidly growing in number. A volunteer to my right smacked one, squealed. Upon inspection, we discovered a bulbous blister at the site of the encounter. They were meaty, I quickly learned, and their blisters, instantly painful. Attracted to light? We killed the bulb, sat in the moonless night, listened to the beating of large wings all around us. Darkness proved no solution. I pulled one from my hair, swatted one from my face. With fingers, cheeks, arms, necks, lips, ankles swelling with red, pus-filled welts, we abandoned our beers and retreated to the only safe place—netted bunks in the sweaty interior. We lay with our arms to our sides, afraid to expose any skin to the swarming bugs.

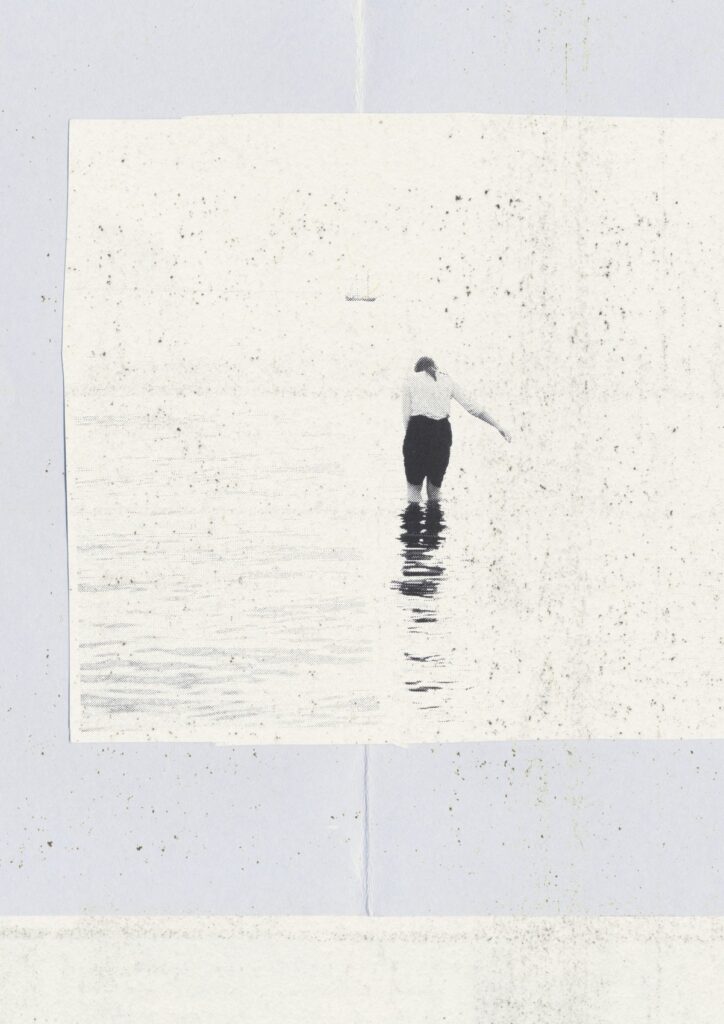

I ended up on an upper bunk, a couple feet from the ceiling. I felt like a forgotten baking sheet on the top rack of an industrial oven. My sleep came and went, as it sometimes does, in a flash. I had no idea what time it was, but I knew morning was far off. Some blisters had broken, exposing sensitive skin. Some still throbbed. My legs cramped and twitched. My bunk sang a squeaky disharmony every time I moved side-to-side, reached to scratch. I couldn’t stay there, I realized, but those damned beetles, though quieted, still occupied walls, windows, floor. I climbed down, slid outside, and just kept going. The stage house was located at the edge of town. I turned to the emptiness of the dark Sahel and followed a path by starlight into the hot night.

I outpaced the bugs and found myself alone. The trail turned to braided confusion. I sat first, then lay down in the dirt. No wind. No respite. Just hot earth against my pillowed hands—a low moment in a series of difficult times I experienced as a volunteer. Whether I slept or not, I can’t be sure, but I rose, dazed, when the moon filled the land with pale light. I turned back toward Mopti and dizzily headed for the brightest light in town.

Arretez-vous, toubabou! Levez les mains. (Stop, white man! Put your hands in the air).

The command was accompanied by the sound of a rifle being cocked and much panicked shouting. Apparently, I’d taken a wrong turn. I had no identification on me and didn’t know the French word for blister beetle. Three soldiers escorted me at gunpoint to an office, ordered me to sit still until morning. Two of them remained stationed at the door. Aside from the initial shock of having a gun point at me, I don’t remember being scared; I was pretty sure I wasn’t an undercover CIA officer. Peace Corps would work this all out.

Though I’d never heard the term back then, my white privilege—especially potent given the circumstances—had kicked into overdrive. During a fairly intense interrogation the following morning, during which my imperfect French continued to pose a problem, a Malian officer repeatedly asked me, “Just what the hell are you doing here?” or something to that effect. His irritation blossomed into full-blown anger. Even with the desk pounding, I failed to become intimidated. Eventually, after some back-and-forth with Peace Corps headquarters, I was released and allowed to board a bus to Bamako.

The family Meloidae, I recently learned, contains approximately 2,500 species of blister beetles. When pressed or rubbed, the beetle reflexively bleeds—though, to be precise, beetles, like most invertebrates, contain hemolymph, not blood. Both fluids distribute nutrients and hormones throughout the body, but blood contains hemoglobin and is confined to blood vessels, while hemolymph lacks red blood cells and flows freely in an open cavity called the hemocoel. So, in fact, blood and hemolymph, while analogous, are simply not the same.

The beetle’s blistering agent, cantharidin, is secreted in its hemolymph as a defensive agent. This chemical is also known as “Spanish fly,” an ancient and ill-advised aphrodisiac. When taken orally—by drying and crushing blister beetles—cantharidin causes inflammation of genital organs, male and female. The swelling, however, can be extremely painful and excessively long-lasting. A minor dosage error can prove fatal. Many people—women, especially—have died by surreptitious, accidental poisoning. And because of its powerful effects on the uterus, Spanish fly has been used to induce abortions, often with dire outcomes. The crushed bugs have also found their way into animal feed, killing numerous horses and other livestock.

Today, many years later, I sit here, alone at my desk, with hot tea (and no insects), reminiscing about that night and researching blister bugs. Of course, those beetles didn’t mean to cause me so much trouble, nor have they ever intended to kill horses, serve as date rape drugs, or cause fatal erections. And their most common modus molestia, producing welts on human skin, is simply an innate defense mechanism. But man, those blisters really hurt. I recall too that, while many Malians welcomed our presence in their country, others did not. In the long history of Peace Corps in Mali, volunteers were routinely ridiculed, accosted in the street, threatened, assaulted, and even murdered. At the time, I couldn’t fully understand the animosity. But now, looking back on it all, I find myself wondering about the blistering that we—despite our best intentions—may have inflicted on those we were trying to help.

Joshua A.H. Harris is the author of Unorthodoxy, an award-winning novel about a man obsessed with his microbiome, and Common Sense 2019, a political pamphlet addressing the corrupting influence of money in politics. His writings have appeared in Common Ground, East Bay Times, Gravitas, Berkeley Times, and Ars Poetica. For more information, visit www.joshuaahharris.com.