Girls Like Me

Katharine Bost

You are probably my mother’s age. With rust-colored hair that curls to your shoulders, and I am envious of those curls’ order. When you read from your notes, you wear glasses perched on the end of your nose. Otherwise, you slide them off. They have a string around the back so they can dangle by your neck.

You seem like the kind of neighbor who, on Halloween, gives out king-size candy bars. The kind of person I would look at and wonder what sin are you attempting to absolve?

Your smiles are nice, the same way that Ted Bundy’s were. Or maybe Ted Bundy’s psychiatrist. Charming, to put a patient at ease. To assure me that you’re here to help.

You are not here to help me.

Girls like me can’t be helped.

“Sarah tells me that you’re feeling angry still,” you say, consulting the notes my therapist has provided you. You tap your pen on the edge of the page. The incessant tapping makes me want to rip the pen from your grasp and throw it across the room.

But I’m trying to assure everyone here that I’m fine, and throwing your pen would not help my cause.

The room we’re in is stifling. You sit very close to me. Not in a predatory way, but the room is the size of an office cubicle. Our knees are about a foot apart, and there is a small table to your right where you keep your notes, your coffee thermos, and tissues. Your glasses when you aren’t reading. Behind you, a bookshelf full of psychology books.

To my right, there is a small, circular wooden table that houses tissues and magazines. Encouraging pamphlets. How to live with depression. Clarifying the stigma behind OCD. You’re not alone.

I want to tear them in half and staunch my bleeding wounds with their pages. Pamphlets and magazines don’t quiet the turmoil.

“Yes,” I say. In my hands, there is a Styrofoam cup with a lid. It’s not fancy, and it’s not big. Just an innocent way to tote around Baileys.

When we talk, I feel like you don’t understand what I say. You twist it. My words are threads, and you bunch them up into tangles.

“She says you’re still cutting,” you say. “Is that true? I can’t tell when you wear sweatshirts.”

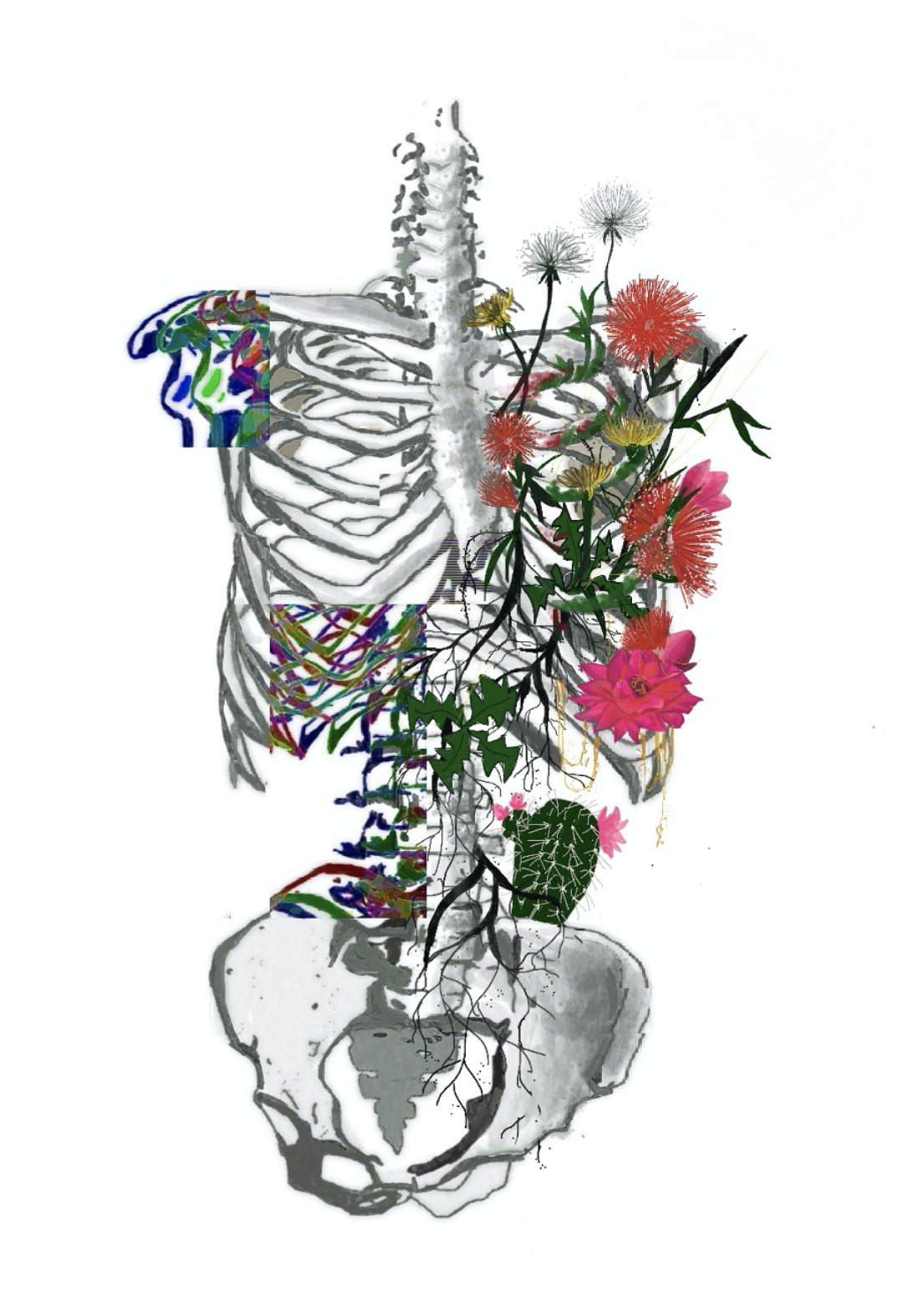

It’s why I wear sweatshirts. People don’t understand cutting. They see scars and think it means something is damaged, and while that’s true, it’s not the complete truth. There is always more. I cut because I need to control something in my life. I need to feel something other than debilitating sadness. Oppressive anger at myself. Emptiness.

“Yes.” I sip my Baileys. “Because I’m angry.”

You jot something in your notes. “At other people?”

“Myself,” I say, fingers tightening around the cup. “Why would I be angry with other people? They didn’t do this to me.”

Do this to me. What have I done to me? The cuff of my sweatshirt creeps up a bit. Reveals the swollen red slashes. The puckered skin, itching to be scratched.

“No,” you say, but I don’t know why your mouth hesitates around the word. A silence falls between us, broken only when you slurp your coffee. “You have trouble controlling your anger, and that’s why you harm, right?”

“Yes,” I say, but there feels like more to it. More to me. Maybe there is not. Maybe I am as empty as I have always imagined.

I long to feel something more than this. To be something more than this.

“I have a note here that you almost crashed your roommate’s car,” you say. “What happened?”

I shrug. “I ran a red light.”

“Why?”

“Because I could.”

You nod, like what I’ve said makes perfect sense. Everyone else I’ve spoken to doesn’t understand. I doubt you do, either. It wasn’t just because I could. It was because I wanted to see what I could do before someone stopped me. Before someone yanked me from the car and told me to settle the fuck down before I hurt someone. Before I hurt myself.

But no one does. I drive past at thirty over the speed limit, and no one cares. I run red lights, and no one stops me.

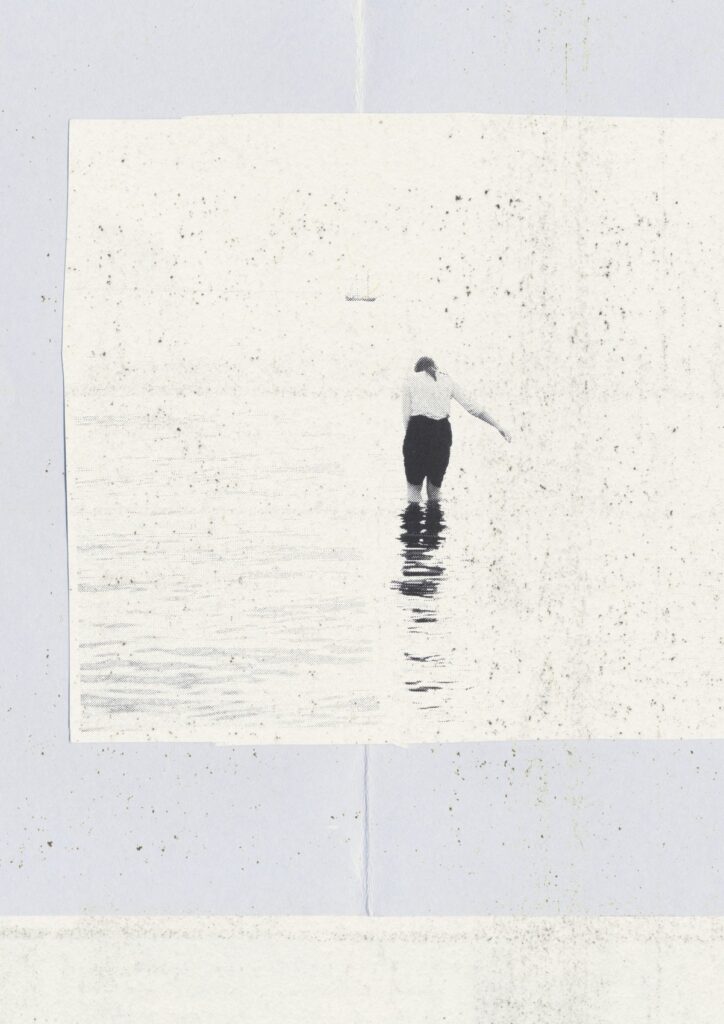

I want to be stopped. Please, stop me. Make me stop.

“How’s your eating? Sarah says you have lost more weight. I can never tell with your baggy clothes.” It’s a joke, I think, but neither of us laugh.

You and Sarah talk about everything, which I guess is fine. I told her she could tell you everything, when she suggested I see you. I think she’s in over her head. In our first session, she told me she was a graduate student, and I have no idea why she’d want to continue counseling me other than she must get a lot of extra credit. Maybe I’m inspiring her to write an essay. Her thesis. Good for her.

“The weight,” you say. A hint of impatience tints your voice, which is probably not a good thing for a psychiatrist to show. Maybe I bring out the worst in everyone, not just myself.

“I don’t know,” I say, though we both know I do. It’s a lie, but not a very good one, and I can tell you know.

You mark something else in your notes. Underline it. Then it’s time for the next question.

“Do you date a lot?”

Who would want to date me? It doesn’t seem like an appropriate response to your question, so I shrug. Busy myself by drinking more Baileys.

“Not really.”

I think about the long list of boys I have kissed. I started it when I got to college. A test. To see if I was as gross as my high school boyfriend thought I was. As much of a joke as everything thought I was.

The boys here must feel sorry for me. I stopped counting when I passed one hundred. Every kiss was as desensitized as the last. I’m broken.

But deep down, I know there is more.

When you lean over the back of your chair to sort through the bookshelf behind you, I think of the girl from the frat party. The one who spilled a drink on my hand, and helped me clean it up, even though I didn’t need assistance.

The one who pulled me past the crowd of drunk, dancing bodies to an empty hall. Who pushed me against the wall and kissed me.

Afterward, she asked, “Have you ever been kissed like that?”

I hadn’t.

Even in that moment, I thought of the many people I’d kissed. And when she kissed me again, it was strawberries and vodka.

She was so perfect, so beautiful. I never got her name.

I’m glad I didn’t. I’m glad I will never see her again. She will remain on her pedestal for the rest of our lives, and she will never fall. She will never be anything less than perfect, because she was perfect in those moments.

She will never know how terrible I am.

“No recent relationships?”

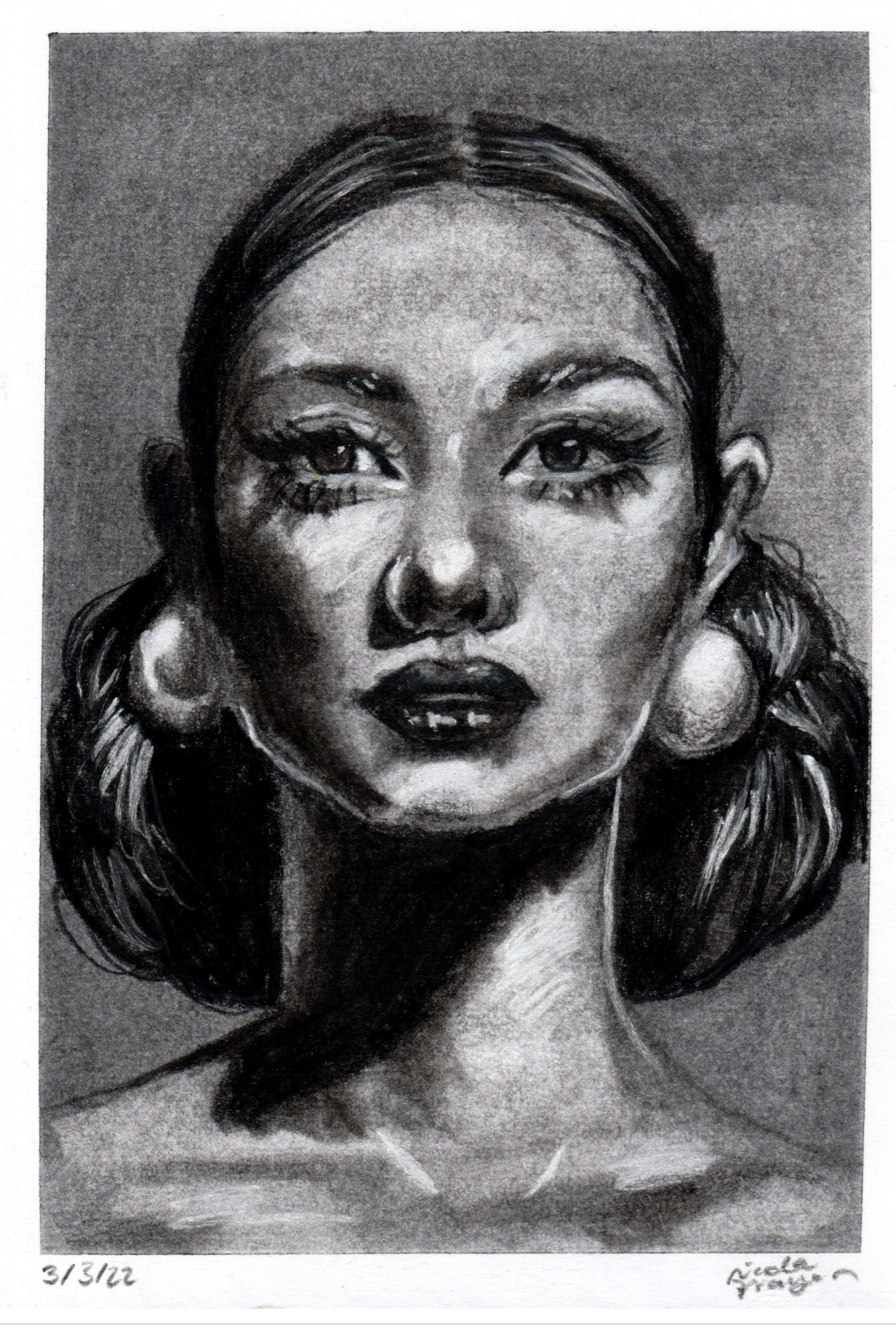

I think of her dark hair, the turquoise streak along the right side, the curve of her nose. The red silk of her shirt, satiny in my fingers.

“None.” My travel cup is empty. The tang of Baileys clings to my throat, and my tongue is heavy. I set the cup on the ground and hope I don’t kick it over.

“Katharine, would you say that you feel displaced often?” You lean forward. When you cross your legs, you nudge my shin. There is a thick book on top of your notepad, but when I try to see what it is, you tilt it out of my reach. Block my line of sight with the notepad.

“Yes,” I say, and I think of the times I have had out-of-body experiences. Where I’ve felt my mind separate from me, drifting away as if it, too, wanted to abandon me. “It usually happens when I’m mad. I just… lose control. Sometimes I black out. But other times, it’s like I’m two different people. I’m me, I’m the person in an argument or in front of the mirror with a boxblade in their hand. But then I’m also a second person, standing back, observing the argument. Observing the self-harm.”

You nod, a quizzical frown on your lips. I don’t know if I’m making sense.

“It’s like I’m watching a football game, and I’m in the stands. But I’m also on the field. I’m two places at once. Does this… make sense?” My hands are shaking, and I feel raw. Like I’ve scraped away my shields, and there is nothing left to protect me.

I hate myself, but even more than that, I want to stop. I’m tired, and I don’t know how much longer I can go on this way.

So many parts of my brain scream for me to end everything, and I’ve tried. But I’m not even good enough to succeed at that.

A small smile edges onto your face. “I have a few more questions for you,” you say. “We’ve established you have constant feelings of abandonment and emptiness. These don’t recede, even when you feel inexplicable anger. Is this true?”

“Yes.”

“Do you feel like you don’t have an identity? That you don’t know what makes up ‘Katharine’?”

“Yes.” It’s something I search for, in the deep crevices of my mind and online, as if forums can tell me who I am.

Above all things, I am pathetic. But I don’t know if that’s an identifying factor.

“I know you engage in reckless behavior,” you say, but it’s more to yourself. “Careless driving and substance abuse.” Your eyes flicker to my empty cup when you say substance abuse.

My friends always joke that it’s not considered alcoholism if we’re in college. I don’t think you’d agree with us.

“You frequently practice suicidal behavior,” you say. Again, it doesn’t sound like it’s to me. “Are you ever paranoid?”

I shift in my seat. “Not, like… kind of? I feel like people are always talking about me. That they’re always laughing at me. If someone’s walking behind me, and they’re whispering, I think they’re making fun of me. Is that vain?”

“Not vain,” you say, marking something else in your notes. You close the book and place it on the table.

DSM IV.

“You have borderline personality disorder,” you say, and for some reason, you seem happy about it.

I’m not. I took an abnormal psych class last year, and I remember reading about this disorder and thinking glad I don’t have to deal with that.

The extensive paranoia, the feelings of self-doubt and self-loathing. The chronic emptiness and disillusionment. The displacement and disassociation.

I don’t want that. I don’t want to be so removed from reality.

“Are you crying?” you ask. That smile is gone from your face. A puzzled quirk of your brow is in place. “Katharine?”

Am I crying? I touch the corner of my eye. Yes, I’m crying. I don’t know why. Ashamed, I lower my head. Shield my eyes by staring at my lap.

“Borderline isn’t that big of a deal,” you say. “It’s not like I told you that you have schizophrenia.”

With my head still bowed, I glare up at you. It has nothing to do with other people, or thinking my life is so much better or worse than others. The fact that you think this causes the blood in my veins to run hot. My cuts itch, and I scratch at them. One of the scabs splits, and warm liquid coats the tips of my fingers.

It has an instant calming effect. Normally, I have to look at it, see the blood seep from my skin, analyze the stream, but right now, it’s enough just to feel it.

“You’re right,” I say. I lift my shoulder to wipe away the sole tear with my sweatshirt.

“We should up your dosage, too,” you say. “I’ll write the script for you. I’m thinking of adding a third medicine…”

My eyes lose focus as I stare at my wrist. Underneath the sweatshirt, I am losing blood. Not a lot of blood, but enough to calm me. I press the fabric to my skin and watch the red bleed into the grey.

It is beautiful. The same color as the shirt the girl from the frat party wore. I think of her, but her face is blurring in my mind, obscured by dark hallways and strobe lights.

The cuff of my sweatshirt is silky, smooth, damp.

I stand in the doorway, watching myself press the fabric. Watch how the fabric is dyed red. Watch while you tell me about an added medication, and how you want to see me back in a few weeks.

“Do you think,” the me in the chair asks, “broken people can ever be whole again?”

Another scab rips beneath my searching fingers, and the sharp sting recombines my selves. I’m no longer in the doorway, but you look behind you, as if you could tell I had just been standing there.

“That depends,” you say, still staring at the doorway. “On whether they’re willing to stop picking themselves apart long enough to let themselves heal.”

Katharine Bost holds an MFA in creative writing from Miami University, and her work has appeared in Last Resort Literary Review, The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review, Tangled Locks Journal, and Mikrokosmos, among others.