Wearing Flames to the Grocery Store

Jasmine Ledesma

I’m wide awake. I haven’t slept at all in the past three days. I spent last night alternating between riding the subway and crooning tangy pop songs for all the empty beehive buildings I passed. My neurons have been bursting and tripling. I’ve been manic for three weeks now, but I refuse to call it anything resembling illness. I’m just confident and dramatic. Doing everyone a favor.

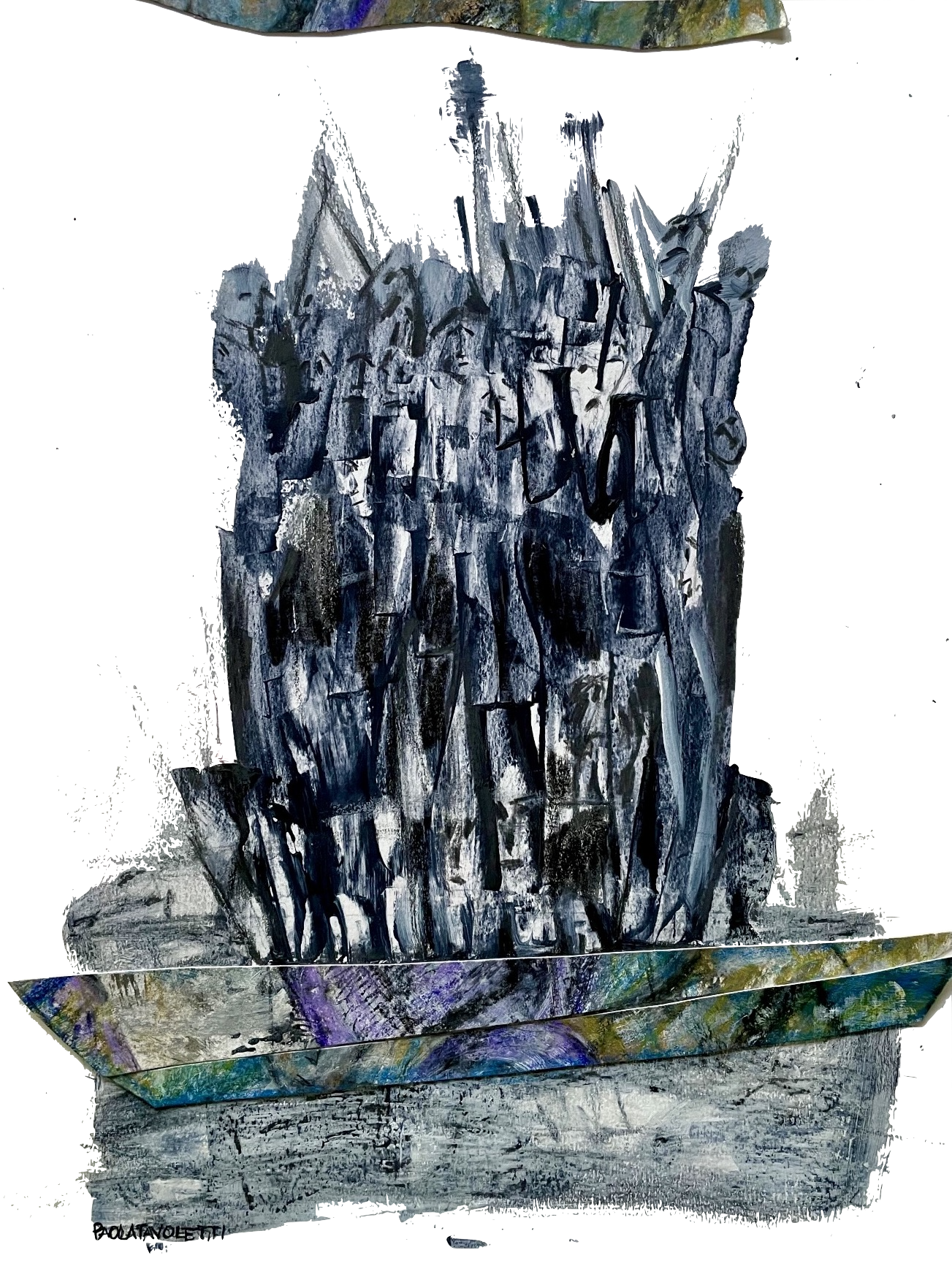

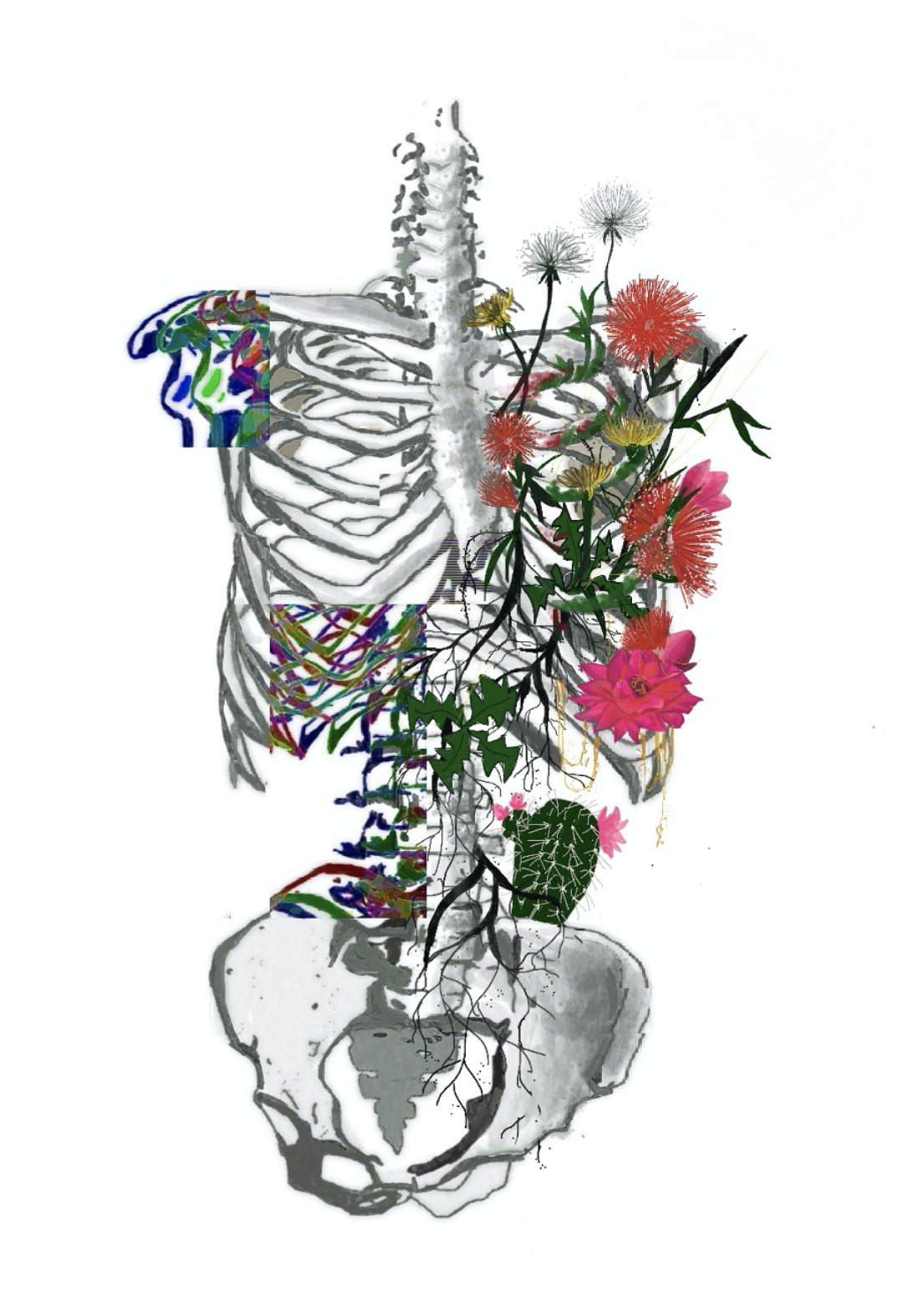

Mania is a dog in a dog costume. By definition, it is an extremely, intensely elevated mood that lasts for long periods of time. And it is not fun. It takes away your appetite; your need for sleep; your ability to think, act and speak coherently; your patience to endure sitting for longer than a few minutes; and your capacity to see the world around you for what it is — an empty hallway. In return, you feel an overwhelming sense of euphoria. An obsessive optimism. You’re beautiful and everybody can see that because they are also beautiful. You can’t stop laughing at nothing. You are chosen and it doesn’t matter what you’ve had taken from you because look at all you can do. Like singing with a bloody nose or waltzing with shadows. Each time I have a manic episode, I return to myself with the edges blurred a little more than before. I am not the person I was originally meant to be. Before the illness struck at sixteen, I was so shy I’d cry at the thought of having to talk on the phone. I used to think I owed my life an apology.

A month prior to this, I flushed my medication down the toilet in the middle of the night. The gooey, pink pills had no trouble drowning. For days leading up to the flushing, I convinced myself that I was cured, my evidence how still I had remained all summer. I held onto my composure like a box, did the dishes and woke up early to finish books. And it wasn’t the 1800 milligrams of Lithium salting my brain every day, I insisted. It was a gift. I’ve been diagnosed with bipolar disorder five times and if I am to be believed, cured five times as well.

But I’m boring you.

All my glorious fight and fuel has led me to Dunkin’ Donuts. Tucked away in Park Slope, Brooklyn, between a closet pretending to be a bookstore and one of many dog salons, the ambient, orange light seething through the bullet-proof glass convinces me to swing the front door open.

Once inside, the store smells like the memory of coffee. One other customer sits at a single table near the restroom, an older man with lint-colored hair, ignoring his own grim reflection as he watches something on his phone, an unassuming cup of coffee to his left. He yawns, his mouth expanding into just another hole to fill. We lock eyes as his mouth closes, but I look away.

I approach the Dunkin’ Donuts counter as if at a bar – fingers drumming, bouncing on my heels. The countertop is sticky with what I hope is caramel. The cashier, standing at the far left side of the store near the coffee machine, peers up from her phone to acknowledge me. Her eyebrows raise like curtains. As she comes closer, I eye the menu on the wall behind her. I’ve been living on twenty-five-cent lollipops from various bodegas and lukewarm soup I reheat every few days. A stew of vegetables softened with boiled tap water. Already having had enough lollipops to turn my tongue an Easter basket grass green, I decide to order a drink.

The cashier is an older woman, her face defined by wrinkles around her mouth like ripples in a swimming pool. Wooly, solo-cup red hair has been wrapped into a high ponytail. A small, brown freckle lives directly beneath her left eye. I want to evict it with my thumb.

“You’re so beautiful,” I spurt, my words an avalanche I can’t predict. “Is that weird? It shouldn’t be. We need contact. I hate donuts.”

I giggle like we’re old friends.

She twists her face into a synonym of a smile, matching my laughter with nervous, hitched breath.

“You don’t want coffee, do you?” She pushes a piece of hair that has fallen out of her ponytail behind her ear.

I don’t get it.

“Can I have a frozen chocolate?” I ask. “Wait, does that have milk in it? I can’t have milk. I’ll die.”

“We can use soy milk. Is that all?” she asks, her eyes half-open.

I nod, sound-tracking my agreement with a hum.

“That’ll be five dollars, then,” she says.

As I reach into the bottom of my wilted backpack, the door opens and we both turn our attention towards two women walking in. Wearing identical, gigantic, sleek sunglasses that, when coupled with their fuzzy, curly-haired black coats, make them look like murderers who know they’re getting away with it.

I pay with five crumpled bills, the very last of my money. The rest has gone towards useless items – a disposable camera that refuses to turn on, shirts that wanted nothing to do with me, a bouquet of flowers I left in a trash can, and a keyboard I know nothing about. The money was meant for groceries and transportation. It’s fine, though. I’ve got good karma.

I slide down to the end of the counter and note that in-between ordering and paying, the man with lint-colored hair has ditched us. Beyond the women ordering lattes and the grave drone of cars outside, there is an Elvis song playing quietly. As if from another dimension that hasn’t fully sealed up yet. I’d recognize that glitter twang anywhere. I sway, but not to the music. To my heartbeat – that bitch that won’t stop flinching. The women have paid offstage and now join me in the waiting room. The one standing on the left smiles automatically.

“I like your glasses,” I say, smiling back. “And your coats. Where did you get them? I’ve always wanted a fur coat. A really big one.”

“Somewhere in Midtown,” the one on the right offers after a beat of silence, her voice like honey in my mouth. “I’m not sure.”

“That’s so beautiful,” I say. I haven’t stopped smiling.

“Here you go,” the cashier says, setting my drink down on the counter. The medium-sized plastic cup drowns in chocolate slush. I poke a straw into the middle of it all.

“Thank you!” I say, a sudden soprano. Holding my drink in one hand, I wave two fingers at the murderer-women and head back outside, pushing the door open with my knee and shoulder.

The mid-afternoon air smells like sweet tea and sludge. This part of Brooklyn looks like a toy set – delicate details everywhere. A ring of bright blue plastic hanging from a bike gate waves in the wind. Crinkled leaves tornado, trying to build up the courage to leave. Empty green bottles clink together near the drain, making music only ghosts understand. I sip my drink until my teeth sting. I’m so lucky to be here.

Within several blocks, I finish half the drink and leave the rest, now chunky and watered down, on a stoop for somebody else to enjoy. I head towards Prospect Park, only a few blocks away.

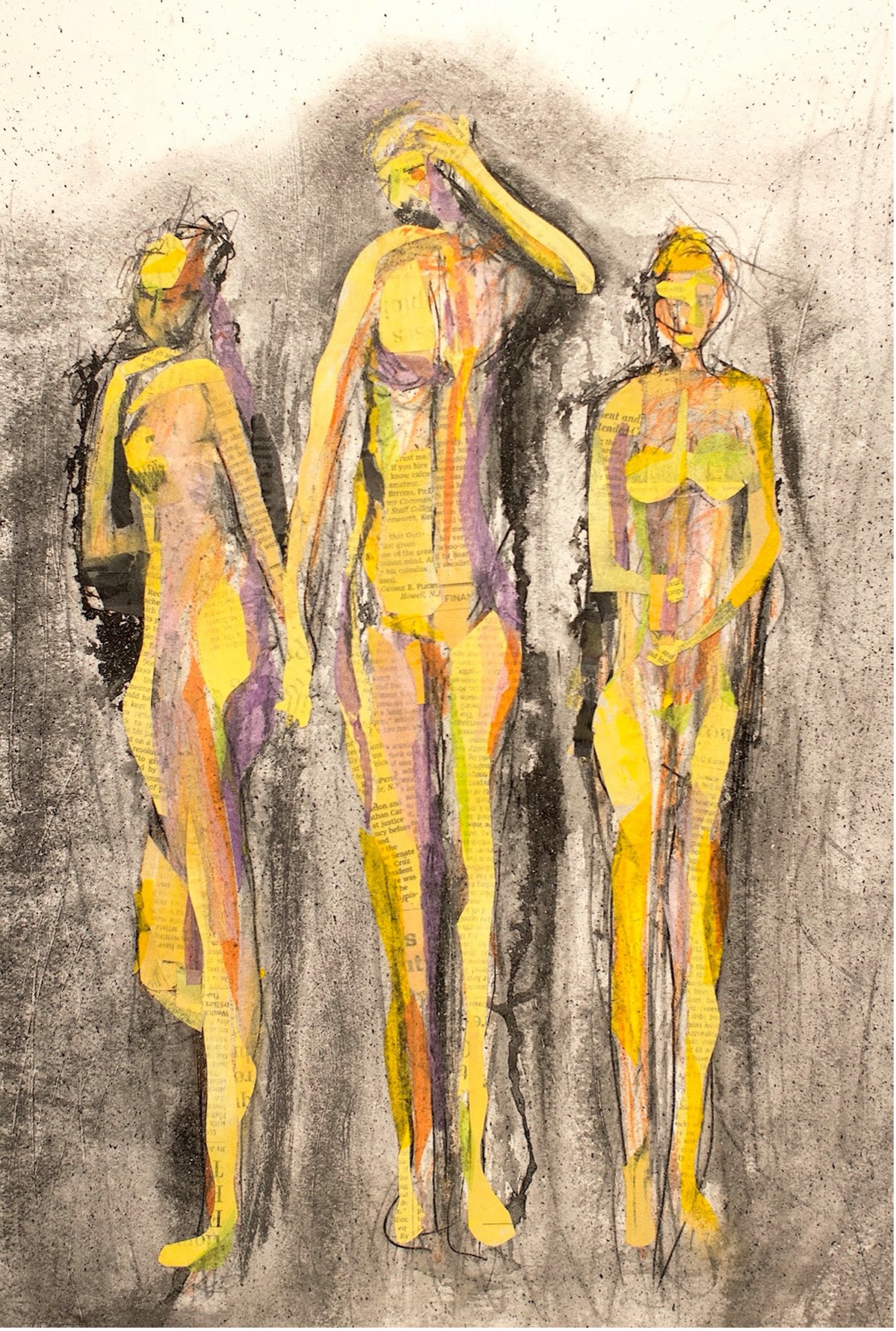

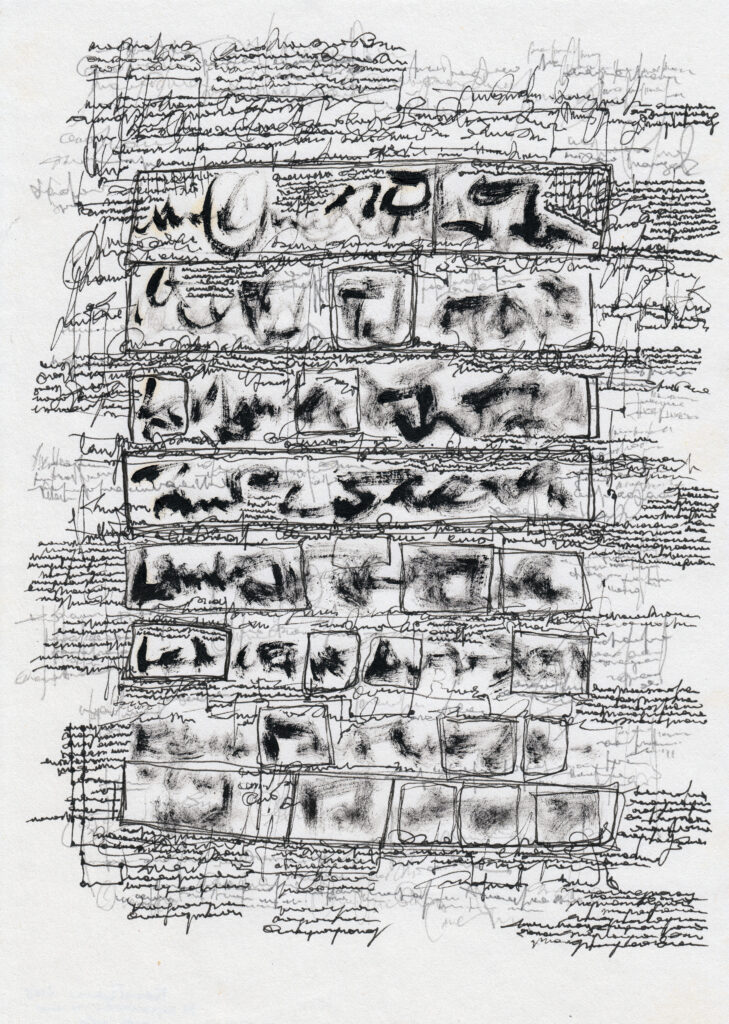

I turn into the park – all of its hilly majesty winking at me – and seek out the kindest looking patch of grass. I decide on a spot near the most biblical-looking tree, branches sprawled out with absolute precision, empty of everything but sky. I lie down on my stomach, covering pebbles and twigs with my body. Dig into my backpack again, this time pulling out my notebook and a pen. I begin scratching words onto the paper. The ink is wet. My thoughts are collaging against one another – I exist outside of poppy seeds. Don’t touch the stove. I have the gusto to become a politician!

Writing feels like bleeding. Grandiosity tastes like champagne, making me the only sweetheart I need. I call myself pet names, stroke my hair, make promises I can’t keep. I’m so talented! Nobody has what I have. Nothing ever tries to kill me. As I write, belly down on the ground, I imagine performing my poetry for theatres of people beneath neon lights. I’ll take my awards to go. I write in imaginary cursive – an alphabet of capital letters with various squiggles connecting them together. A week later, I won’t be able to read what I have written.

The minutes pass like rain down a gutter. I sit up, my brain red hot and sharp as a knife. I want to do math, badly. Instead, I throw my notebook and pen back into my bag and feel around until my hand finds the box of matches I bought this morning. I set the box on my leg and peel it open. I find obscene, almost perverted pleasure in running the green alien tip against the gritty side of the box and listening to the shriek of fire bursting into existence. I let the flame dance down, getting as close to my fingers as I can stand before waving my hand around and putting it out. I flick the shriveled, blackened scrap of wood into my bag and pick out another match to start over with.

This game goes on until an older man wearing a bright orange shirt and beige shorts that showcase his knees walks along the nearby path, pauses in his tracks, and takes a long look at me, trying to decide whether or not to say something. I squeal, hurry the matches into my bag, and run off, laughing like a live studio audience.

Dashing straight out of the park, I sort of hope the man is chasing after me. It would be fun to be hunted like an animal. All I’d have to do is survive. The air feels like silk against my face. I’m blushing from the inside out and everybody can see it. They want me. I’m manna, I swear.

After a couple of blocks, I slow down and gradually go back to walking. As I wait for the light to change at the intersection of 10th and 11th Streets, I whip out my phone and check my email, ignoring the phone calls and messages I’ve missed. My mom wants to know if I’m doing drugs. Gianni, a girl I’ve been going on dates with for the last few months, wants to know if she did something wrong last time we hung out. Why did I leave like that? I ignore her, too. I’ve kissed her wrists. She should know better than to question me.

For the last few days, I’ve been sending Governor Cuomo emails every morning about my plans to make public transportation more reliable and accessible to everybody. These ideas range from putting garbage cans in every subway car to creating a sticker version of the MetroCard. He hasn’t responded yet, but it’s only a matter of time. I put my phone back in my pocket.

It is getting late now. Dinner should be happening. The sky’s the color of melted metal, an apocalyptic blue. All the psychopathic businessmen are funneling in and gushing out of bars. They couldn’t go home if they tried. I walk up and down the same block, my heart racing away from me.

In fourth grade, my teacher showed my class a video of a crash test dummy smashing into a wall. The plastic head flew off, and we all knew the arms would never grow back — no matter how many times we begged her to rewind the video. We wanted to watch the car drive straight into the wall, over and over. Self-destruction felt unbelievable. Until I got older and learned how to make pain feel like home.

Nobody in my life knows what to do with me when I get sick. My friends are broke and well-meaning, but the most they can offer is vodka and cartoons. In between hospital stays, I’ve lost friends on account of being “too much” to handle. My mother, even with states between us for most of the year, refuses to acknowledge my illness. Despite bearing the brunt of it. It’s always her money I steal. Her room I destroy. Still, she is the first one to tell me I am faking. That I should grow up and stop being so selfish. Don’t I ever think about how this makes her look?

I have lived with my dad in south Brooklyn for the last couple of years. He knows I have an illness but only a fuzzy idea of what it means. I skip classes or I don’t. I buy groceries or I don’t. I wear band-aids or I don’t. Mostly, out of inherent embarrassment, I try to hide when I am not doing well. Don’t look at me, I’m oozing. He used to say he didn’t believe in mental health issues. It was all a scam to get people addicted to pills. He used to have such fun telling me that.

My phone is at fifteen percent. I curl my hair around my fingers and consider my options. I could ask someone to kill me. Somebody who would look nice with a tear tattoo. I’d say, push down but not too hard. Make sure I’m smiling. Do me pretty. I could take the bus to its final stop and beg someone to take me in. I could steal. I could pretend. I could ask a doctor to sedate me. I could scratch. I could go limp or down or away. I could and could and could.

I couldn’t.

I’m sick.

I have done horrific things to myself and those around me because of my illness. Things that, when spoken aloud during the occasional group therapy session, elicit shock from the veteran manic depressives. It’s not fucking fair. I pull a strand of my hair out and watch it go limp in my hand. Somebody has to carry me. I don’t care if it hurts.

I decide to call my dad.

I slump against the backside of a restaurant, facing the street. The ground is cold, but I welcome it. I dial my dad’s number with my neglected middle finger. As the phone rings, I focus on the way the ground beneath me stays still. Like I’m erosion.

He answers within three perfect rings.

“Hello? Jas?”

I can hear the TV mumbling on his end. The night I am about to ruin. I’m nervous about unraveling so I begin right away.

“Dad, I’m worse than you think!” I clench my fingers unconsciously. “Or, I’m worse than you know, I guess.”

I pause for a moment, letting the words sink into his brain.

I continue: “I’m manic again. Everybody can tell. I’m touching people to see what will happen. I got this stupid fucking tattoo. I’m so dizzy but,” I laugh so I don’t cry, “I mean to be. It’s all me.”

I hang up as soon as I’m finished, letting out a groan of relief. I’ve been screaming for years. I hope he heard me. Within seconds, my phone is buzzing. I pick up after five nauseating rings.

“Where are you?” he asks, immediately.

“Park Slope,” I say, watching a car pass by. Like a shark.

“Can you come home?” he asks.

I nod, though he can’t see me.

“Just come home, yeah? Then, we’ll make sure you’re okay,” he insists.

I make a noise like agreement and hang up again.

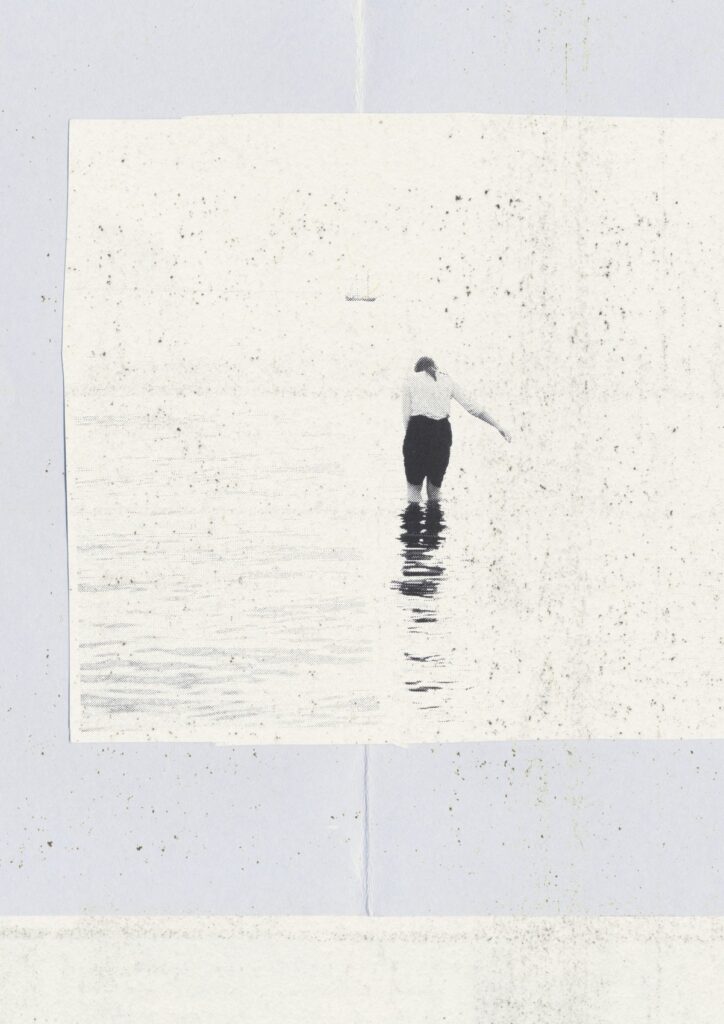

An hour passes before I can stand back up. The street is ugly. Clumps of people pass me, bouncy with evening alcohol. The nearest train is only a few avenues down so when I do stand up, I turn to my right. The air should slap me. I never wanted to be incoherent. Just wanted to feel good. For once, forever. But nobody can survive being set on fire. Not even the holiest of monks. I reach the subway station and head underground. My phone is dead now.

As I rattle around on the train with everyone else, I look at my reflection in the glass above the empty row across from me.

My makeup has smeared across my face like dried blood. My hair is a crucifixion. I’m the thirteenth zodiac sign, I’m a slut. Everything I own is stolen.

I close my eyes.

I could have had it all.

Jasmine Ledesma is a writer based in New York. Her work has appeared in or is set to appear in places such as Crazyhorse, Rattle, and [PANK] among others. Her work has been nominated for Best of The Net and twice for the Pushcart Prize. She was named a Brooklyn Poets fellow in 2021. Her novella Shrine was listed as a finalist for the Clay Reynolds Novella Prize. Her poem was highly commended by Warsan Shire for the Moth Poetry Prize.